Exploring Language Change: Historical Linguistics and Social Perspectives

Language change is an inevitable phenomenon driven by various factors such as social, geographical, and individual variations. Misconceptions surrounding language change often lead to negative views, while causes like fashion and social identity influence linguistic trends. Through a case study on the emergence of the word "bonk," the dynamic nature of language evolution becomes apparent, showcasing how words can enter and shape a language over time.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

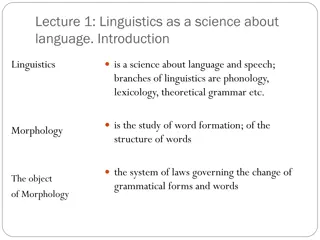

Historical Linguistics Phonology and Social Linguistic Theories Excluded

List of Content 1. The fact of language change 2. Lexical and semantic change 3. Morphological change 4. Syntactic change

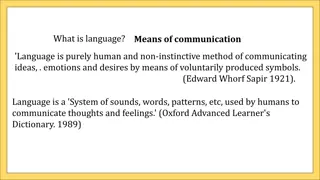

The Fact of Language Change Inevitability of Language Change. Language is in a constant state of flux, evolving not just over centuries but on a daily basis. This change is driven by a myriad of factors, including social, geographical, and individual variations, making it an inherent characteristic of all spoken languages.

The Fact of Language Change Misconceptions about Language Change. Many people are not aware of the changes happening in their language or tend to view these changes negatively, attributing them to laziness or a decline in linguistic standards. Historical perspectives, such as those of Jonathan Swift, who lamented the changing nature of English and advocated for its standardization and preservation, highlight these misconceptions.

The Fact of Language Change Causes of Language Change. There are various reasons behind language change, including fashion and social identity. Teenagers, for instance, often adopt new linguistic trends as a means of social identification, which contributes to the dynamic nature of language.

The Fact of Language Change Case study: Bonk !. In Britain today, the most usual everyday word for copulate is bonk. No issue of a British tabloid newspaper is complete without a headline featuring bonking schoolgirls or bonking vicars . The word is inescapable. But it wasn t always like that. In 1986 a sly reporter at Wimbledon asked the [German] tennis player Boris Becker a question about bonking . Becker famously replied, The word bonking is not in my dictionary. This was hardly surprising: in 1986, the word bonk wasn t in anybody s dictionary at least, not in the relevant sense. Today, everybody who s spent half an hour in Britain knows this word, presumably including Boris Becker, and, if you consult a good recent British dictionary of English, you will find the word entered there between bonito (a type of fish) and bonkers (meaning, of course, crazy ). But, if your dictionary is older than about 1987, you probably won t find it. What conclusions can we draw? Well, one possible conclusion is that you need to buy a new dictionary. More importantly, though, we can conclude that a new word has entered English in the last few years. The word bonk came into use only around 1985 or so, and the dictionaries picked it up a couple of years later. To put it another way, English has changed in

The Fact of Language Change Language and Identity. Language change is also tied to issues of identity and social standing. The way individuals adopt or resist linguistic changes can reflect their social aspirations or affiliations.

The Fact of Language Change Linguistic Variation. Variation is a natural part of language evolution. This variation can occur across different social groups, regions, and even within individual speech, contributing to the complexity of studying language change.

Lexical and Semantic Change Introduction to Lexical and Semantic Change. Undoubtedly the most conspicuous type of language change is the appearance of new words. When a new word appears in the language, there will be an occasion on which you hear it for the first time, and you may well notice that you have just heard a new word and remember the occasion. Examples of Semantic Change. Television, dirty bomb, gay

Lexical and Semantic Change Borrowing. Semantic borrowing happens when languages are in contact. Speakers of multiple languages copy words from one language to another. Words that are borrowed are called loan words. Example of borrowing. Kayak from Eskimo language, whisky from Scottish Caelic.

Lexical and Semantic Change Calque, or loan translation. Calque is a new word or phrase constructed by taking a foreign word or phrase as a model and translating it morpheme by morpheme. Example of borrowing. Syn-pathia -> com- passio

Lexical and Semantic Change Combining forms. Extract morphemes that can then be imported and used as building blocks for constructing words in another languages. Example of borrowing. Greek thermos heat and metron measure

Lexical and Semantic Change Morphological treatment of loans. Turkish finds it awkward to borrow verbs directly and prefers to borrow nouns that are then turned into verbs with the dummy verb etmek. This is, in fact, quite a common practice: Japanese borrows foreign verbs in the same indirect manner by taking over nouns and combining them with its verb suru do : hence the Chinese loan benkyoo study produces the Japanese verb benkyoo suru study , and Japanese is full of verbs borrowed indirectly from English, like hitto suru make a hit , doraibu suru drive a car , kisu suru kiss , and pasu suru pass an exam . Verbs like etmek and suru are sometimes called light verbs, meaning that they have little or no semantic content of their own and serve only to provide a usable verbal form of an item that carries the semantic content of a verb but which is formally a noun..

Lexical and Semantic Change Morphological treatment of loans. Even nouns may produce morphological complications for the borrowing language, however. In the majority of languages, nouns are inflected for number, and in many languages they are also marked for case and/or grammatical gender. Borrowed nouns must be fitted into all this morphology in one way or another, and the result may be disturbances to the borrowing language s morphology.

Lexical and Semantic Change Number. With just a handful of exceptions like feet and children, English nouns form their plural with an invariable suffi x -s: books, cars, discos, databases, CDROMs, and so on for virtually every noun, old or new. With borrowed nouns, however, we agonize and vacillate. Many nouns borrowed from Greek and Latin have been taken over complete with their foreign plurals: hence phenomena, indices, crises, formulae, cacti, bacteria, and some dozens of others (or hundreds, if we count purely technical terms like protozoa and hominidae). Such un-English plurals disrupt the ordinary English morphology, and speakers often fi nd them confusing and rearrange them in various ways. We formerly had singular datum and plural data, but the more frequent plural form just doesn t look like a plural to English eyes, and most speakers now treat data as a singular (as in This data is interesting ; compare the earlier These data are interesting , now confi ned to a handful of conservative speakers many of whom are actually linguists!), and data now has no plural. Something similar is perhaps happening with criterion/criteria, phenomenon/ phenomena, and bacterium/bacteria: very few of my students seem to be at all sure which form is the singular and which the plural, and use them the wrong way round as often as not: this criteria, these phenomenon, a new bacteria.

Lexical and Semantic Change Case. In German, the problem of dealing with loan words is made still more acute by the fact that the language has a case-system and naturally different classes of nouns take different sets of case- endings. Table 2.1 shows just a few of the patterns that exist; the names of the cases are Nom(inative), Acc(usative), Gen(itive), and Dat(ive). Loan words that take the -s plural are accommodated in an unexpected way: with just one exception, they simply don t take any case-endings, as shown in Table 2.2. The one exception is that certain nouns do take the genitive singular ending -s, even though this makes the genitive singular look just like all the plural forms. In Russian, which has a substantially more complex case morphology than German (six cases and well over a dozen different patterns for forming them), most loan words are treated in the same way: they just don t take any case-endings at all.

Lexical and Semantic Change Compounding. Compounding refers to combining two or more existing words into a new word. It can be head-final or head-initial. Copulative compounds. Both members are equally heads, like tragicomic. Exocentric compounds. A compound in which there is no head, like forget-me-not (a kind of flower).

Lexical and Semantic Change Derivation. Derivation is the process of creating words by adding affixes. Productivity of an affix. The degree of freedom with which it can be used to derive new words. The ancient English suffi x -th is now totally unproductive: it occurs in a few old formations like warmth and depth (and, slightly disguised, in height and weight), but it can no longer be extended to other cases: things like *happyth and *bigth are impossible. The suffi x -dom is chiefl y found in a few old formations like freedom and kingdom, but it has never quite died out entirely: stardom is a recent formation, and we occasionally come across new instances of its use, like gangsterdom, tigerdom and even girldom.

Lexical and Semantic Change Conversion. Conversion is the process of moving a word from one lexical category to another, with no affixation or other modification. Example. Verb drink to noun drink.

Lexical and Semantic Change Clipping. Extracting a word from a longer word of the same meaning. Blending: Pieces of existing words are combined to make a new word. E.g. smoke + fog = smog.

Lexical and Semantic Change Clipping. Extracting a word from a longer word of the same meaning. Blending: Pieces of existing words are combined to make a new word. E.g. smoke + fog = smog.

Lexical and Semantic Change Back formation. The creation of a word by the removal an apparent affix from another word. English remove affix like editor to create words like edit. Reanalysis. Interpreting a word as having a structure that is not historically valid and hence obtaining a new morpheme for use in coining other words. Hamburger is from Hamburg. burger is than extracted to form cheeseburger, chickenburger.

Lexical and Semantic Change Semantic change. Change in meaning. Shift in markedness Taboo and euphenism Generalization, specialization Melioration, pejoration Metaphor Metonymy and Synecdoche

Lexical and Semantic Change Gresham s law of semantic change. New meanings completely replace old meanings

Lexical and Semantic Change Traugott's Tendencies. Present Elizabeth Traugott's three tendencies in semantic change that include the movement from external descriptions of reality to internal descriptions of perceptions, the shift towards textual meanings, and the increasing basis of meanings in the speaker's subjective beliefs and attitudes.

Lexical and Semantic Change Tendency 1. external descriptions of reality become internal descriptions of perceptions and evaluations. Cases like the semantic shift of boor farmer to oaf illustrate this tendency, as does the observation that English feel, which once meant only touch (an external description), now denotes the perceptions of the person doing the touching.

Lexical and Semantic Change Tendency 2. external and internal descriptions become textual meanings that is, they acquire meanings that give overt structure to discourse. English while formerly meant only period of time , as it still does in cases like Wait for a while. But it eventually acquired the discourse function of the period of time (during which something happens) , as in While my wife was away, I lived on pizza. Later still, it acquired the more abstract discourse function of although : While she s very talented, she s somewhat careless. English but originally meant on the outside (of) ; it acquired the sense of except for , which it still has in a few cases like everything but the kitchen sink; today, however, it mostly occurs with the discourse function of contrast: It s perfect, but it s too expensive.

Lexical and Semantic Change Tendency 3. meanings become increasingly based in the speaker s subjective beliefs and attitudes. Here are several examples. The word apparently originally meant openly, in appearance . It then acquired a weak sense of evaluation: to all appearances . In the nineteenth century, it acquired the strong sense of evaluation of evidence which it now has, as in She is apparently determined to pursue this. Similarly, probably once meant only plausibly, believably , but today it also expresses the speaker s evaluation of evidence: She is probably going to be promoted. The verb insist originally meant persevere, continue . In the seventeenth century it acquired a new sense of demand , as in I insist that you come home early. A century later, it acquired the sense of believe strongly : I insisted that a mistake had been made.

Lexical and Semantic Change Exercise.

Morphological Change Morphological change. Changes in the morphological structure of lexical items and of inflected forms, and change in morphological systems.

Morphological Change Reanalysis. The process where a word historically having one particular morphological structure is perceived by speakers to have a different structure, leading to the creation of new forms. Examples include the evolution of the word "bikini" and its reanalysis to "monokini," illustrating how reanalysis can impact word formation.

Morphological Change Metanalysis. A type of reanalysis involving nothing more than the movement of a morpheme boundary. E.g. unicorne -> une icorne -> licorne

Morphological Change Analogy. The assumption that an acquired morphological rule apply to a under morphological changes. Proportional analogy. E.g. drive -> drove, dive -> dove,

Morphological Change A key fact about analogy is that it can sometimes block or reverse the effect of a regular phonological change. For example, there was a change in English by which /w/ was lost after /s/ and before o: hence sword has lost its /w/ in speech, although we still retain the traditional spelling. The same thing should have happened in forms like swore and swollen, but these are nonetheless pronounced with /w/ today. We are not sure quite what happened, but we know the reason is the existence of the related forms swear and swell. Either the analogy of these forms, which always retained their /w/, prevented the regular sound change from affecting swore and swollen, or the change did apply but the /w/ was later restored by the analogy with swear and swell. In the first case we speak of analogical maintenance; in the second, of analogical restoration.

Morphological Change Sturtevant s paradox. Sound change is regular, but produces irregularity; analogy is irregular, but produces regularity.

Morphological Change Contamination. Word-formation processes illustrate various types of analogy. One of them in contamination, referring to the irregular change in the form of a word under the influence of another with which it is associated in some way. E.g. the opposite of male was femelle, but constant paring of the two words made is female.

Morphological Change Hypercorrection. Another type is hypercorrection. This occurs when a speaker deliberately tries to adjust his or her own speech in the direction of another variety perceived as more prestigious but overshoots the mark by applying an adjustment too broadly. E.g. Someone from England trying to acquire an American accent will carefully insert non-native /r/s into words like dark and court, but may overdo it and produce things like avocardo. Most Americans, however, lack the British contrast between do and dew; when they attempt to acquire the British diphthong in dew and new, they occasionally overdo it and produce things like What shall we dew? Such hypercorrections are easily visualizable as instances of four-part analogy: new /nu:/:/nju:/ :: do /du:/:/dju:/.

Morphological Change Universal principles of analogy. The first law: a complex marking replaces a simple marking. A standard example of this is provided by German. Old High German, the ancestor of modern German, had a variety of patterns for constructing plurals. One of these was exhibited by nouns like gast guest , plural gesti, in which the stem-vowel undergoes the change called umlaut under the influence of the vowel in the plural suffix. This noun comes into modern German as Gast, G ste, with a double plural marking (umlaut plus suffi The fi rst law: a complex marking replaces a simple marking. A standard example of this is provided by German. Old High German, the ancestor of modern German, had a variety of patterns for constructing plurals. One of these was exhibited by nouns like gast guest , plural gesti, in which the stem-vowel undergoes the change called umlaut under the infl uence of the vowel in the plural suffi x. This noun comes into modern German as Gast, G ste, with a double plural marking (umlaut plus suffi x). The Old High German noun boum tree had a plural bouma, with no umlaut, and this should have come into the modern language as Baum, *Baume. Instead, German has Baum, B ume. The double plural-marking has been extended from cases in which it is historically normal (like Gast) to others in which it is not regular x). The Old High German noun boum tree had a plural bouma, with no umlaut, and this should have come into the modern language as Baum, *Baume. Instead, German has Baum, B ume. The double plural-marking has been extended from cases in which it is historically normal (like Gast) to others in which it is not regular

Morphological Change Universal principles of analogy. The second law: a derived form is reshaped to make it more transparent and especially more similar to the simple forms from which it is derived. The Modern English word housewife began life as a compound of Old English w f woman and h s house, farm . This was a title of some prestige since, in combination with its male equivalent, the ancestor of husband, it implied free peasant status and the right to freehold ownership of land. As with many high status titles of this type, it became an honorifi c for any (married) woman and, eventually, became associated with a woman whose primary employment was in household work. When it was written, it was generally done in the way we still spell it. But it was not pronounced in this way. Evidence from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries suggests that the mainstream pronunciation was / h s f/ or, occasionally, / h si/, with the usual variation depending on geographical and social background. This type of contraction is by no means uncommon with titles, Mrs, from Mistress, being a particularly striking example. The early modern period seems to have been particularly given to this, as largely obsolete titles such as Goodwife, pronounced/ gudi/ or its variants, and often spelt Goodie, demonstrates

Morphological Change Change in Morphological Type. The most dramatic type of morphological change: the replacement of the entire morphological system of a language. Isolating language. A language where there is no morphology at all. In an agglutinating language, a single word may consist of several morphemes, but each morpheme is a clearly distinct form.

Morphological Change In an inflecting language, a word typically consists of several morphemes, bur morpheme boundaries are difficult or impossible to identify: instead, the several morphemes are wrapped into a tight package.

Morphological Change Nineteenth-century linguists were often inclined to assume a natural direction for such changes: isolating languages develop into agglutinating languages by compounding, and agglutinating languages develop into infl ecting languages by complex phonological changes. And such developments are certainly attested. For example, classical Chinese was a paradigm case of an isolating language, but modern Chinese is different. It has acquired a number of suffi xes, such as the plural suffi x -men (wo I , women we ; t he, she , t men they ), the completed-action suffi x -le (q go , q le went ), and a number of wordforming suffi xes like -li power (y nli vision , from y n eye ; m li horsepower , from m horse ) and -du degree (ch ngdu length , from ch ng long ; r du temperature from r hot ). It has also acquired a very large number of compounds: hu ch train , from hu fi re and ch vehicle ; b ic i cabbage , from b i white and c i vegetable ; g m ng revolt, make revolution , from g remove and m ng Heavenly Mandate ; z z completely , a reduplication of z suffi ce . Modern Chinese is beginning to look a bit like an agglutinating language, although it still has a long way to go before it resembles Turkish or Kiswahili.

Syntactic Change Introduction to Syntactic Change. An overview of the recent burst of activity in studying syntactic change, with a focus on the emergence of general principles guiding such changes.

Syntactic Change Reanalysis of Surface Structure. Explains how syntactic change is primarily driven by the reanalysis of sentence structures. Examples include the evolution of copulas in Mandarin Chinese and Hebrew, illustrating how words can shift from one grammatical category to another, leading to significant syntactic transformations.

Syntactic Change Shift of Markedness. Discusses how the frequency of use between marked and unmarked forms can lead to changes in syntactic structures. This includes changes in word order and the grammatical functions of specific constructions.

Syntactic Change Grammaticalization. Describes the process by which lexical items evolve into grammatical markers, affecting sentence structure and meaning. Examples include the development of the "going to" future tense construction in English, which evolved from a literal expression of movement to a marker of future intention.