Understanding the Social Construct of Race and Racism

Racism cannot be understood without defining race. In sociology, race is considered a social construct with no biological basis. Physical differences like skin color do not determine group differences in ability or behavior. The historical evolution of the concept of race and its use in justifying exploitation and violence are discussed. The consensus among scientists is that race is not a biological category, and genetic variation is greater within racial groups. The distinction between race and ethnicity, particularly in terms of perceived physical characteristics versus common ancestry and culture, is highlighted.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

SOCIOLOGY SUSMITA ROY 10.08.2021

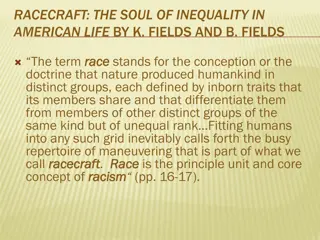

Racism cannot be defined without first defining race. Among social scientists, race is generally understood as a social construct. Although biologically meaningless when applied to humans physical differences such as skin color have nonatural association with group differences in ability or behavior race nevertheless has tremendous significance in structuring social reality. Indeed, historical variation in the definition and use of the term provides a case in point. The term race was first used to describe peoples and societies in the way we now understand ethnicity or national identity. Later, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as Europeans encountered non-European civilizations, Enlightenment scientists and philosophers gave race a biological meaning. They applied the term to plants, animals, and humans as a taxonomic subclassification within a species. As such, race became understood as a biological, or natural, categorization system of the human species. As Western colonialism and slavery expanded, the concept was used to justify and prescribe exploitation, domination, and violence against peoples racialized as nonwhite. Today, race often maintains its natural connotation in folk understandings; yet, the scientific consensus is that race does not exist as a biological category among humans genetic variation is far greater within than between racial groups, common phenotypic markers exist on a continuum, not as discrete categories, and the use and significance of these markers varies across time, place, and even within the same individual (Fiske, 2010).

Definitions Racism cannot be defined without first defining race. Among social scientists, race is generally understood as a social construct. Although biologically meaningless when applied to humans physical differences such as skin color have no natural association with group differences in ability or behavior race nevertheless has tremendous significance in structuring social reality. Indeed, historical variation in the definition and use of the term provides a case in point. The term race was first used to describe peoples and societies in the way we now understand ethnicity or national identity. Later, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as Europeans encountered non European civilizations, Enlightenment scientists and philosophers gave race a biological meaning.

They applied the term to plants, animals, and humans as a taxonomic subclassification within a species. As such, race became understood as a biological, or natural, categorization system of the human species. As Western colonialism and slavery expanded, the concept was used to justify and prescribe exploitation, domination, and violence against peoples racialized as nonwhite. Today, race often maintains its natural connotation in folk understandings; yet, the scientific consensus is that race does not exist as a biological category among humans genetic variation is far greater within than between racial groups, common phenotypic markers exist on a continuum, not as discrete categories, and the use and significance of these markers varies across time, place, and even within the same individual (Fiske, 2010). For most social scientists, race is distinct from ethnicity . A major distinction is the assumption of a biological basis in the case of race. Races are distinguished by perceived common physical characteristics, which are thought to be fixed, whereas ethnicities are defined by perceived common ancestry, history, and cultural practices, which are seen as more fluid and self-asserted rather than assigned by others (Cornell and Hartmann, 2006). Thus, Asian is usually considered a race , whereas Tibetans and Bengalis are considered ethnicities.

Although ethnicity and nationality often overlap, a nationality, such as American, can contain many ethnic groups (e.g., Italian-Americans, Arab-Americans). Yet, all three categories - race, ethnicity, and nationality are socially constructed, and, as such, groups once considered ethnicities have come to be seen as races and vice versa. Moreover, some groups who are now taken for granted as white , such as the Irish, Italians, and Jews, were once excluded from this racial category. The definitional boundaries of race and ethnicity are shaped by the tug and pull of state power, group interests, and other social forces. From a sociological perspective, it is this social construction of race not its natural existence that is the primary object of inquiry in the study of racism. Bundled up with eighteenth century classifications of various racial groups were assertions of moral, intellectual, spiritual, and other forms of superiority, which were used to justify the domination of Europeans over racialized others. In the North American context, racist ideology served as justification for land appropriation and colonial violence toward indigenous peoples as well as the enslavement

of Africans starting in the sixteenth century. It was later used to justify the state-sanctioned social, economic, and symbolic violence directed at blacks and other minorities under Jim Crow laws. In the mid-twentieth Rights Movement, global anticolonial movements, and increasing waves of non-European immigration to the West changed how individuals, groups, and nation-states talked about, viewed, understood, and categorized race. A major task for sociologists has been to assess these changes and their implications for racial discrimination and inequality. century, the American Civil What are the mechanisms of racism? According to Taguieff (1997), biological or essentialist racism denies to all human beings the possibility of sharing the same humanity. Consequently, the difference becomes a stigmatization or a symbolic exclusion that allows a group of people to consider itself as superior by looking down at another group and setting up negative stereotypes. As a result, racism is based on a hierarchy of physical differences. In fact, racism is not only a network of attitudes, beliefs, and convictions; it also refers to behaviors, practices, and actions. Racism is a social construction (Exama, 2005, Moussa, 2003 ,According to Gould, cited by Pollock (2001),

For understanding the mechanisms of racism, we need to consider the roots of prejudices and of stereotypes that are associated with categories we grew up with, learned, and experienced. Stereotypes are connected to attitudes, beliefs, and values, whereas prejudices refer to opinions without any critical judgment (Allport, 1979). Stereotypes and prejudices are part of the elaboration of social norms. A stereotype is a sort of shortcut, often based on previous experiences or beliefs, whereas prejudice is a preconceived idea, a prejudgment of someone or something. Both stereotypes and prejudices contribute to the elaboration of racism as well as ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism Ethnocentrism refers to the way we look at the world from our perspective or from our filter of meaning (McAndrew, 1986). Here, we use our as a collective identity. It assumes that our understanding is the only valuable understanding. As an example, the Western world representing the supposedly universal perspective from the Enlightenment is considered a standard or norm, whereas the non-Western world constituted of many other worlds represents the particular: a kind of suprauniversal culture versus many peripheral cultures. Preiswerk and Perrot (1975) identified ethnocentric biases as the way of putting our sociocultural group and its values in a central position.

Arcand and Vincent (1981) also found that the representation of indigenous peoples in Western history schoolbooks is always stereotyped, prejudiced, and marginalized, because the norm that is used to describe their values and to recognize their contribution refers to this universal norm: It is ethnocentrically biased. As a result, indigenous peoples are represented as inferior, primitive, savage, uncivilized, barbaric, and so on, incapable of being civilized and incapable of facing the challenges of a modern society. Rather, close to nature and the past, they are always presented away from civilization and the present. Ethnocentrism is the we and the others perspective: the way that the we looks at the world while looking down at the mimetic others.

NECESSARY FOR RACISM TO DEVELOP ACCORDING TO NOEL AND VENDER ZANDEN. THEY ARE STATED BELOW. 1. VISIBLE PHYSICAL OR CULTURAL CHARACTERISTICS: THE PHENOMENON OF RACISM PRESUPPOSES THE EXISTENCE OF TWO OR MORE SOCIAL GROUPS, IDENTIFIABLE BY THEIR VISIBLE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OR CULTURAL PRACTICES. PEOPLE SHOULD BE AWARE OF DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE GROUPS AND SHOULD BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THEMSELVES AS BELONGING TO ONE GROUP RATHER THAN ANOTHER. ONLY THEN, RACISM CAN DEVELOP. 2. COMPETITION BETWEEN THE GROUPS: IT IS NECESSARY FOR THE GROUPS TO HAVE COMPETITION BETWEEN THEMSELVES FOR VALUED RESOURCES, SUCH AS POWER, LAND, OR JOBS. IN THIS CONDITION OF EXTREME COMPETITION, MEMBERS OF ONE GROUP WILL BE INCLINED TO SECURE THEIR OWN INTERESTS BY DENYING MEMBERS OF OTHER GROUP FULL ACCESS TO THESE RESOURCES. 3. PRESENCE OF GROUPS WITH UNEQUAL POWER: ANOTHER CONDITION OF RACISM IS THAT THE GROUP MUST BE UNEQUAL IN POWER. IN SUCH A CONDITION, ONE OF THEM IS ABLE TO MAKE GOOD ITS CLAIM OVER SCARCE RESOURCES AT THE EXPENSE OF THE OTHER GROUP OR GROUPS. AT THIS POINT, INEQUALITIES BECOME STRUCTURED INTO THE SOCIETY.

Racism is an ideology in the Marxian sense, which is why it is so pervasive. One needs to find the common thread in all forms of racism and their theories by placing them against capitalist society's goals and hegemonic strategies. Debates over racism are truly ideological mystifications. Questions of race effectively come down to questions of ideology. Racism is an ideology that is inseparable from the national or international socio-economic and political situation. A brief study of the Republics of Haiti and South Africa under apartheid illustrates how racial and racist ideologies are manipulated to cover up the exploitation of the masses. DEVELOPMENT AND RACISM IDEOLOGY Ramsay Boly is a full-time graduate student in UC Berkeley s Master of Development Practice program. One of the things I learned when I was negotiating was that until I changed myself, I could not change others Nelson Mandela. Of the many topics in the literature and practice of international development, racism seems to be one of the most relevant and least covered. Racism is a powerful, violent and complex system that will not be given justice in this short post, but I hope to advance the conversation because I perceive it to be a fundamental issue in international development. One of my biggest critiques of development is the apparent lack of concern and urgency to question assumptions. While we acknowledge local participation as progress in development practice, we fail to discuss the original preconceptions that trivialized the identities, knowledge, capabilities and experiences of those individuals and communities.

Cultural Pluralism Cultural Pluralism can be defined as an arrangement in a society where multiple smaller cultures assimilate in mainstream society but also maintain their cultural uniqueness without being homogenised by the dominant culture. The difference in cultural pluralism can be observed between homogeneous societies like Israel, Japan, South Korea which have only one dominant culture and hence no need to accommodate other cultures and heterogeneous societies like United States of America, India, United Kingdom, etc. However, while a lot of societies are heterogeneous i.e. they have multiple cultures, that does not necessarily mean that they are also culturally plural because cultural pluralism requires not just the existence of different cultures within a society but also respect for these cultures by the dominant culture. For example, in Saudi Arabia, while a lot of migrants bring their culture along and the country now has a considerable South Asian diaspora, their cultures are suppressed and relegated to the private realm i.e. they are not allowed to practice their culture openly. Thus Saudi Arabia might be a heterogeneous society but not a culturally plural one.

Often cultural pluralism and multiculturalism are used interchangeably, however, there is one difference. In multiculturalist societies, there is no dominant culture. It is the peaceful coexistence of various small cultures. India has always been proud of its culturally plural society. India has a dominant North Indian, Hindu, Hindi speaking culture however cultures from the south and northeast India like the cuisines (Idli, Vada, Uttapam), dance forms (Bharatanatyam, Kathakali, Bihu), literature (Sangam literature) are not only respected in the rest of the country but gets an equal space in the cultural display on Republic Day. Religious pluralism in the form of the prevalence of mosques, gurudwara, Buddhist, Jain and Parsi temples and their open religious celebration often joined in by their Hindu friends is a testament to India s religious pluralism.

REFERENCES C.N.RAO MAKHAN JHA INDIAN SOCIETY