Understanding Structural Causes of Inequities in STEM Hiring for Increased Diversity

This presentation by Kim Shauman from UC Davis delves into the structural influences that impact diversity levels in STEM faculty recruitment. It highlights factors such as the supply of diversity in the pipeline, representation of women and underrepresented minorities among STEM doctoral degree recipients, and challenges in translating increased diversity in the pipeline to applicant pools. Promising strategies for addressing inequities in STEM hiring are discussed, focusing on utilizing research and data to enhance the faculty search process.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Structural causes of inequities in STEM hiring and promising strategies for increasing diversity Kim Shauman Department of Sociology, UC Davis Using Research and Data to Improve the Faculty Search Process in STEM Disciplines UC ADVANCE PAID Roundtable 1

Structural influences defined Structure refers to the recurrent patterned arrangements which influence the choices and opportunities available. Social, organizational, institutional Cultural, e.g. related to norms, customs, traditions and ideologies Structural influences that help explain low levels of diversity in STEM faculty recruitment Diversity in the pipeline and in the pool of applicants Geographic and family constraints Network position & connections

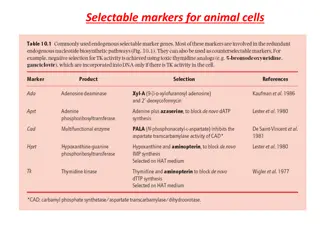

Supply of diversity in the pipeline and recruitment pools Supply of diversity in the pipeline Representation of women among STEM Ph.D.s has increased steadily, but women are still underrepresented Representation of underrepresented minorities has increased but is still low

Supply of diversity in the pipeline and recruitment pools Representation of Women among STEM Doctoral Degree Recipients 60 50 49.4 Biosciences 40 Percent Female Physical sciences 31.1 30 Mathematics 30.2 Computer sciences 21.6 20 Engineering 10 0 SOURCE: National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics, special tabulations of U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Completions Survey, 1989 2008.

Supply of diversity in the pipeline and recruitment pools Representation of URMs among STEM Doctoral Degree Recipients 60 Percent Underrepresented Minorities 50 40 Bachelor's 30 Master's Doctorate 20 17.4 13.4 10 7.2 0 SOURCE: National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics, special tabulations of U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Completions Survey, 1989 2008.

Supply of diversity in the pipeline and recruitment pools Supply of diversity in the pipeline Representation of women among STEM Ph.D.s has increased steadily, but women are still underrepresented Representation of underrepresented minorities has increased but is still low Supply of diversity in applicant pools Increased diversity in the pipeline has not translated into increased diversity in applicant pools

Supply of diversity in the pipeline and recruitment pools Source: Gender Differences at Critical Transitions in the Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty (National Academies, 2010)

Supply of diversity in the pipeline and recruitment pools Source: Gender Differences at Critical Transitions in the Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty (National Academies, 2010)

Explanations for Lagging Diversity of Applicant Pools Image problem of academic science (e.g., Sears 2003) Women more likely to shift orientation away from academic research careers during graduate school Perceived as incompatible with family life/roles Long work hours Tenure clock inflexibility Competitive, chilly climate of academic departments (Ong et al. 2011) Geographic constraints Dual-career couple conflicts for women Time schedule of tenure track coincides with childbearing years Regional preferences for underrepresented minorities Reliance on traditional pool-building strategies (NAS 2010) Traditional advertisement text, traditional advertisement outlets Personal networks are insufficient and tend to reinforce homogeneity Relative attractiveness of non-academic sector Career track flexibility, competitive pay, team-oriented collaborative work, consistency of resources and support

Geographic and Family Constraints Women are more likely than men to be in dual-career couples 93.67 100 Women Men 78.02 80 Percent 60 40 21.98 20 6.33 0 Dual-career couple Have Stay-at-home partner Among dual-career couples, women are more likely than men to be in dual-academic couples 100 Women Men 80 Percent 54.05 52.11 60 47.89 45.95 40 20 0 Have Non-Academic Partner Have Academic Partner Women tend to be younger than their partners Source: Schiebinger, L., Henderson, A. D., & Gilmartin, S. K. (2008). Dual-career academic couples: What universities need to know. Michelle R. Cayman Institute for Gender Research, Stanford University.

Geographic and family constraints Implications for applicant pool: Women may limit their employment search to specific regions Women are more likely to have a series of post-doctoral positions (used to coordinate two careers) or other non-traditional trajectories Increased likelihood of considering non-academic careers Implications for hiring: Hiring women more often entails dual-career hires Negotiations may be more complicated, require more resources, represent a larger investment Women scholars requiring dual-career accommodations are more likely to be pre-tenure

Social networks, hiring, and inequality Social networks tend to be segregated by gender and race/ethnicity Occupational and field of study segregation Homophily birds of a feather . (McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook 2001)

Homophily in social networks From: Gender Stratification in the IT Industry: Sex, Status and Social Capital by Kenneth W. Koput and Barbara A. Gutek (Edward Elgar, 2010)

Homophily in social networks From: Gender Stratification in the IT Industry: Sex, Status and Social Capital by Kenneth W. Koput and Barbara A. Gutek (Edward Elgar, 2010)

Homophily in social networks From: Gender Stratification in the IT Industry: Sex, Status and Social Capital by Kenneth W. Koput and Barbara A. Gutek (Edward Elgar, 2010)

Social networks, hiring, and inequality Social networks tend to be segregated by gender and race/ethnicity Occupational and field of study segregation Homophily birds of a feather . (McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook 2001) Networks of women and racial minorities (McDonald 2011) Are smaller Have fewer connections to high-status individuals Have fewer connections to individuals who are centrally-located in the network Networks of white men Are more homophilous than networks of women and minorities Provide preferential access to information and high-status individuals Provide access to employment references that are well-connected

Social networks, hiring, and inequality Implications for applicant pool: Women and minorities may have limited access to relevant information (e.g., how to tailor an application, to present a good fit with the position and/or department) References for women and minorities may be less well-known than references for white male applicants Implications for recruitment: Reliance on established networks is not sufficient Valuation of recommendation based on the reputation of the referee may reproduce inequities

Strategies for hiring diverse faculty Employ innovative approaches to building applicant pools Extend beyond existing networks, tap networks of women and minorities Successful hires of underrepresented minorities are positively associated with (Smith et al. 2004) Job descriptions that includes a scholarly link to the study of race or ethnicity and/or success in working with diverse groups of students An institutional intervention strategy that bypasses or enhances the traditional search process Searching in a subfield known to include a more diverse population of potential applicants Institutionalize and continually promote policies that facilitate work-life balance (Schiebinger et al. 2008) Dual-career hiring programs Supportive family leave programs

Strategies for hiring diverse faculty Foster and support institutional mindfulness Climate of self-consciousness about processes, criteria, and justifications for hiring decisions Involve administrators in maintaining a strong institutional commitment to diversity (Smith et al. 2004) Involve centrally-located and respected STEM scholars in the process organizational catalysts (Sturm 2007) Individuals with knowledge, influence, and credibility in positions where they can mobilize institutional change Institutionalize the capacity to examine processes, identify problems and successful strategies for solving them Collect relevant data!

Implications of low levels of diversity in STEM faculty hiring Failure to attract talent Many talented scientists are leaving academia Direct loss of talent + indirect loss of potential educators and mentors The presence and activity of diverse faculty in STEM departments would likely increase the retention of women and underrepresented minorities in STEM majors (Page & Carrell 2010) Reduced innovative potential (Page 2007) groups that display a range of perspectives outperform groups of like- minded experts Diversity yields innovative approaches and superior outcomes