Understanding Comparative Advantage in Economics: Adam Smith and David Ricardo

Explore the concepts of absolute advantage versus comparative advantage as discussed by renowned economists Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Discover how free market principles, self-interest, and efficient resource allocation shape beneficial economic decisions. Delve into examples of comparative advantage, labor cost analysis, pre-trade prices, and gains from trade. Learn how production possibilities with increasing costs impact specialization and free trade outcomes.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Chapter 3 Comparative Advantage Questionable example on page 36 Link to syllabus

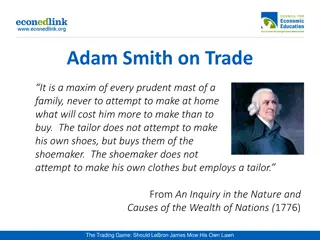

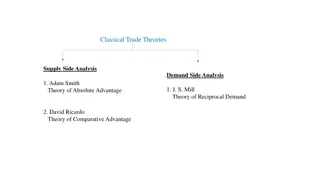

Adam Smith (1723-1790): The Wealth of Nations 1776 Scottish Philosopher. In a free market society, individuals, acting out of their own self interest, will be guided, as if by an invisible hand, to make socially beneficial economic decisions. Also: benefits of free trade, criticism of mercantilism. Smith mistakenly focused on Absolute Advantage, not Comparative Advantage.

David Ricardo. 1772-1823 Born in London; father was a stockbroker. In addition to major contributions in Economics, he was a member of the British Parliament, a businessman and financier. Said to have become interested in economics at the age of 27, after reading Adam Smith, while on vacation. Was friends with James Mill, Bentham, Malthus, and other classical economists.

Ricardian example of comparative advantage. Page 36 0.67 1.5 It s not clear to mt why Pugel makes the numbers for the US the same in the two tables on pages 36 and 37, while the numbers for the Rest of the World are different . It is the case that the discussion in the text on page 36 refers to the numbers as they appear in the table on page 36. So perhaps this is not a case of typographical errors, but poor selection of an example.

Ricardian example of comparative advantage. Page 37 Assume: Notation: let aW be the labor hours to produce one unit of wheat, and aC be labor hours for one unit of cloth (4 and 2 in the US in this example). W/C means units of wheat to get a unit of cloth: 2W/C is two units of wheat for one unit of cloth, PC / PW = 2. If labor is the only cost and it is paid wage , then the price (or cost) of producing one unit of wheat, PW, is equal to wage x aW, and similarly PC= wage x aC. Thus, PC / PW = aC / aW . In other words, the (relative) price of a good is higher if the country is (relatively) inefficient in the production of the good. Pre-trade Prices in Ricardian example p. 38

Figure 3.1 page 41 Gains from trade: constant cost case

(From next chapters Figure 4.1 p. 51). Production Possibilities with Increasing Costs. With increasing costs, free trade will generally not lead to complete specialization.

Figure 2.3 Page 25 Effects of trade on production, consumption and price

Handouts Description of argument of comparative advantage Numerical example of comparative advantage

Solution: P. 45 #8 Country V (Labor=30) Country MR (Labor =20) Pre-Trade Post-Trade Pre-Trade Post-Trade wine chees wine chees wine Chees wine cheese Labor input/unit Q 15 10 same 10 4 same Labor allocation 15 15 30 0 8 12 0 20 Production 1.0 1.5 2 0 0.8 3 0 5 Net Imports -- -- -1 2 -- -- 1 -2 Consumption 1.0 1.5 1 2 0.8 3 1 3 Percentage changes w: 100*(1-1)/1 = 0 c: 100*(2-1.5)/1.5 = 33 w: 100*(1-0.8)/0.8 = 25 c: 100*(3-3)/3 = 0 The pre-trade relative price of wine in terms of cheese in V is 15/10=1.5; in MR it is 10/4 =2.5, so V has comparative advantage in wine, and will export it. The post-trade relative price of wine in both V and MR is 2; the book s phrase is that 1/2 bottle of wine is worth 1 kilo of cheese

Exam Question #5, Fall 2010 Consider now a Ricardian world composed of two countries, (Input/Q) Spain (S) and Chile (C ), and two goods, food (f) and games (g). Suppose the labor input per unit of output for these activities is as indicated in the accompanying table. Which country has absolute advantage in which good? Why? Which country has comparative advantage in which good? Why? What are the limits to the free trade relative price of Food? What will happen to the relative price of food in Spain, if both countries agree to free trade? Assume that Chile has 150 workers. Draw a production possibility curve for Chile, Spain Chile Food 20 25 Games 50 75 Pre-trade PF/PG is 20/50 in Spain, and 25/75 in Chile, so Chile has comp adv in Food. Limits to free trade price of food are .25 and .4 With free trade, the price of food in Spain will fall