Understanding Childhood Obesity: Causes, Risks, and Prevention

Childhood obesity is a growing concern with long-lasting effects. Learn about the causes, risks, and prevention strategies associated with childhood obesity to promote healthier generations.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

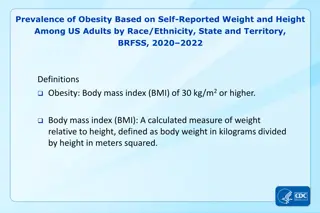

Child body mass index (BMI) at or above the gender- specific 95thpercentile on the CDC BMI-for-age growth charts. Childhood extreme obesity at or above 120% of the gender-specific 95th percentile on the CDC BMI-for-age growth chart. Child a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile on the CDC BMI-for-age growth charts. Child and adolescent obesity and adolescent obesity was defined as a Childhood extreme obesity was defined as a BMI Child and and adolescent overweight adolescent overweight was defined as

Childhood obesity is associated with a higher risk of premature death and disability in adulthood. Overweight and obese children are more likely to stay obese into adulthood and to develop noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) at a younger age. For most NCDs resulting from obesity, the risks depend partly on the age of onset and on the duration of obesity.

Obesity may run in families. The main causes of excess weight in youth are similar to those in adults; they include individual causes such as behavior and rarely include genetics. Behavior causes may include dietary patterns, physical activity, inactivity, medication use, and other exposures. Individuals with lower income and/or education levels are disproportionally more likely to be obese. American society has become characterized by an environment that promotes decreased consumption of healthy food and physical inactivity. One early major risk factor is maternal obesity during pregnancy. Children born to obese mothers are 3-5 times more likely to be obese in childhood.

Children born to women before and after bariatric surgery found that the children born after the surgery were at lower risk for obesity than the children born before the surgery. Women who gain much more weight than recommended during pregnancy have children who have a higher BMI than normal in adolescence. Small gestational age (SGA) newborns have higher risks for abnormal postnatal weight gain and diabetes; they may have long-lasting implications for health, which is possibly because of nutritional effects during the fetal life.

Complications of obesity in children and adolescents can affect every major organ system. High BMI increases the risk of metabolic and CVDs and some cancers; it is also the most important modifiable risk factor for hyperglycemia and diabetes. Adult obesity is associated with a number of serious health conditions including heart disease, metabolic syndrome, and cancer. If children were obese, obesity and these risk factors in adulthood are likely to be more severe.

Children who are obese are at higher risk for (1) high blood pressure and high cholesterol, which are risk factors for CVD; (2) impaired glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes; (3) respiratory problems such as sleep apnea and asthma; (4) joint problems and musculoskeletal discomfort; (5) fatty liver disease, gallstones, and gastroesophageal reflux; (6) psychologic stress such as depression, behavioral problems, and bullying issues at school; (7) low self-esteem and low selfreported quality of life; (8) impaired social, physical, and emotional functioning.

The diagnosis of obesity depends on the measurement of excess body fat. BMI may be an imperfect measure of body fat and real health risk. BMI is a convenient screening tool that correlates fairly strongly with body fatness in children and adults. BMI age-specific and gender-specific percentile curves (for 2-20 year olds) allow an assessment of BMI percentile (available online at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts). For children younger than 2 years of age, weight-for-length measurements greater than 95th percentile may indicate overweight and warrant further assessment. Child and adolescent obesity was defined as a BMI at or above the gender-specific 95th percentile on the CDC BMI-for-age growth charts. A BMI for age and gender above the 95th percentile is strongly associated with excessive body fat and co-morbidities. Extreme obesity was defined as a BMI at or above 120% of the gender- specific 95th percentile on the CDC BMI-for-age growth chart.

Early recognition of excessive rates of weight gain, overweight, or obesity in children is essential because the earlier the interventions, the more likely they are to be successful. Routine evaluation at well child visits should include the following: 1. Anthropometric data calculation of BMI. 2. Dietary and physical activity Anthropometric data, including weight, height, and Dietary and physical activity history. history.

Assess blood pressure, adiposity distribution (central versus generalized), markers of co- morbidities (acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, hepatomegaly, orthopedic abnormalities), and physical stigmata of a genetic syndrome (explains fewer than 5% of cases).

All 9-11 year olds should be screened for high cholesterol levels. Other useful laboratory tests may include hemoglobin A1c, fasting lipid profile, fasting glucose levels, liver function tests, and thyroid function tests (if there is a faster increase in weight than height).

Prevention is the key to success for obesity control. There are three levels of prevention in dealing with childhood obesity: (1) primordial prevention as it deals with keeping a healthy weight and a normal BMI through childhood and into teens; (2) primary prevention aiming to prevent overweight children from becoming obese; and (3) secondary prevention directed toward the treatment of obesity so as to reduce the co-morbidities and reverse overweight and obesity if possible.

The approach to therapy and aggressiveness of treatment should be based on risk factors including age, severity of overweight and obesity and co- morbidities, and family history and support. The primary goal for all children with uncomplicated obesity and fast-rising weight-for-height is to achieve a healthy balance of energy consumption as a caloric intake, healthy activities In the perinatal maternal weight gain, good blood sugar control in diabetes, and postpartum weight loss with healthy nutrition and exercises. During infancy 6 months followed by inclusion of solid foods, providing a balanced diet with avoidance of unhealthy calorie-rich snacks, and close monitoring of weight gain should be emphasized. healthy eating, with the number of calories used with the activities and activity perinatal period this includes adequate prenatal nutrition with optimal eating, with the number of calories used with the and activity patterns. patterns. infancy, early initiation of breast feeding, exclusive breast feeding for

During the preschool into practice includes providing nutritional education and guidance to parents and children so as to develop healthy eating practices, offering healthy food preferences by giving early experiences of different food and flavors, and following closely the rate of weight gain to prevent early adiposity rebound. In school-aged children, this includes monitoring both weight and height, preventing excessive prepubertal adiposity, providing nutritional counseling, and emphasizing daily physical activity should be emphasized. In adolescence growth spurt, maintaining healthy eating behavior, and reinforcing the need for daily exercise are most important. preschool age period, putting these strategies adolescence preventing the increase in weight after a

The traffic light diet nutritional goals with the following categories: (1) green-GO includes foods that are low in calories and can be eaten without any restrictions; (2) yellow- CAUTION includes food items with moderate to high calorie content that can be eaten only in moderation (3) Red-STOP includes high-calorie food items that should be avoided or eaten rarely. Physical activity is the key component for prevention and management of obesity. Preschool children require unstructured activities and thus will benefit from outdoor play and games. On the other hand, school children and adolescents require at least 60 minutes of daily physical activities, so instead of recommending a wide open schedule to walk or bike to school more, suggest walking or biking to school two or more days a week. traffic light diet may be useful in promoting

More who have not responded to other interventions. The initial interventions include a systematic approach that promotes multidisciplinary brief, office-based interventions for obese children and promotes reducing weight. Before enrolling any patient in a weight-loss program, the clinician must have a clear idea of that individual's expectations. Patients with unrealistic expectations should not be enrolled until these are changed to realistic andattainable goals. Using the pneumonic described, the clinician should guide the patient who seeks weight reduction to create SMART goals: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Timely More aggressive therapies aggressive therapies are considered only for those SMART

Anorectic drugs are not recommended for routine use, and the efficiency and safety of these drugs have to be established by controlled clinical trial. surgical effective solution for certain children and adolescents. However, the role of bariatric surgery in the treatment of obese children or adolescents is controversial. The concerns about surgery to treat obesity in young populations include whether or not surgery is cost-effective, how to ensure healthy growth through to adulthood, what support services are needed after surgery, compliance with the postoperative nutrition regimen, and attendance at appointments for long- term follow-up and care. There is very limited evidence available to adequately estimate long-term safety, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, or durability of bariatric surgery in growing children. surgical treatment treatment may be advocated as a preferred and cost-