Understanding Caste in India: A Historical and Political Perspective

Caste in India is a complex system deeply intertwined with religion, history, and society. It is a hierarchical structure that dictates social organization, power dynamics, and economic relationships. The system, comprising varna and jatis, perpetuates inequality and marginalization, with long-standing roots dating back to ancient times. This comprehensive overview delves into the nuances and specific features of caste, shedding light on its impact and implications in Indian society.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Caste in India: A Historical and Political Approach

Common Model What Is CASTE?

Caste and Other Hierarchical Ideas/Practices Caste and Other Hierarchical Ideas/Practices Caste refers to ideologies and practices that justify INEQUALITY In that respect caste is no different from other such ideologies practices across the world that do the same Think of RACE and GENDER: Both underpinned by ideologies and practices whose ultimate aim is to justify inequality For one example, see, Gerald D. Berreman, an American scholar of India, Caste in India and the United States in the American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Sep., 1960), pp. 120-127 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2773155

Specifics While comparable, there are some specific features of caste we need to understand. Three striking and specific features are: Caste has come to be recognized as being closely tied to RELIGIOUS ideas (Hinduism) Caste has a VERY long history, the earliest vocabulary associated with caste ideologies can be seen in the VEDAS, circa. 1500-1000 BCE Over time has developed a SYSTEMATIC form, and practiced by many non-Hindu groups too. The systemicity of the caste system has been greatly exaggerated though

What IS Caste? A hierarchical system of ideas (called varna) about organization of society At various times in history these ideas have shaped the exercise of power and empowered some groups and disempowered others Caste has been linked to occupational groups (called jatis) Jatis often ranked by varna, but the same jati in different places and at different times could be associated with different varna categories (no systemicity ) Because of links with occupation, jati-varna, closely linked with ECONOMIC power Jatis practice endogamy (marry within jati), commensality (eat together), and share ritual occasions. As a result jati is closely connected with kin networks Jati was and often is much more of a lived social unit, NOT VARNA If we MUST call caste a system, then it is better described as the varna-jati system It is a system that has seen corporate (collective) but not individually-based mobility The jati-varna system justifies and tries to perpetuate inequality Allows for marginalization of some social groups, especially those seen as outside of caste, or outcaste

An A-historical history Because of its connections with religion, Western scholars (starting with European Orientalists of the 17th and 18th centuries) want to understand caste only through TEXTS, and perceive it as a singular SYSTEM. That is the origin of the notion of THE CASTE SYSTEM Like many other forms of knowledge, this idea was made part of universal knowledge via colonialism The word itself reflects this. When the Portuguese first came to India in the 16th century, they saw in the local hierarchies, something similar to hierarchies with which they were more familiar That great source (!), Wikipedia, tells us, Casta is an Iberian word meaning "lineage", "breed" or "race." It is derived from the older Latin word castus, "chaste," implying that the lineage has been kept pure. Casta gave rise to the English word caste during the Early Modern Period

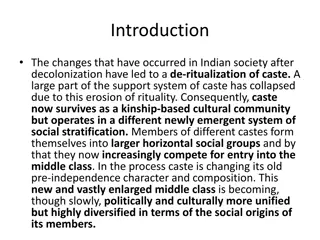

Historical Approach Caste has been: Always as much about POWER as anything else, and reflected configurations of POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL and CULTURAL of a particular time Because configurations of power CHANGE, so has caste . Unlike what high school social studies books (or lazy searches of the internet) might say, caste has ALWAYS been changing. It is VERY FAR FROM AN UNCHANGING SYSTEM This is why it is important to always relate caste to a HISTORICAL CONTEXT and focus on a history rather than a sociology of caste

Origins in Pre Modern India In the Early Rig Vedic Era ~ 1500 BCE we come across the word VARNA The people who use this term are mostly recently arrived immigrants who were cattle herders, nomads, who lived in relatively egalitarian lineage groups Varna in their language (Sanskrit) means color and classification Varna is used hierarchically, but only to distinguish between themselves, Arya (the noble ones) and the Dasa (the servile, the people they had overcome) It is hardly a system of any sort though

Changing Varna By the Late Rig Vedic Era ~1000 BCE the word varna was used to distinguish people WITHIN the ARYA group as well With the Purusa Hymn we get both the idea of a fixed hierarchy AND a mythological justification for that hierarchy The hymn divides people into four categories Brahmins (priests); Kshatriya or Rajanya (warriors/lords of land); Vaisya or Vis (commoners), and Sudras (the servile ones) This happens as the Arya people are transitioning from nomadic to settled life. They have greater material surpluses and hence also emerging inequalities But, varna categories are still fluid. The son of a Brahmin could be Kshatriya, etc. By ca. 800 BCE 400 CE as polities (states/empires) and economies (greater division of labor) becomes more complex, we note references to JATIs (probably best described as occupational categories)

Challenges to Varna Between 600 and 400 BCE there were a number of challenges to the varna ideology and Brahmin superiority A significant challenge from heterodox sects such as Buddhism whose teachings made varna hierarchies irrelevant to their followers Kings and emperors embraced heterodoxies, including perhaps the greatest emperor of ancient India, Ashoka Brahmins were marginalized, as was the importance of varna Though this was followed by a period of reassertion of Brahminical power, challenges continued, most vividly by hugely popular devotional movements of the 15th and 16th centuries

Consolidation of Varna ca 500 CE ca. 500 CE though, Brahmin orthodoxy made a come back, and Buddhism was (often violently) virtually exterminated from India The same era sees the emergence of PRESCRIPTIVE texts, called dharmashastras (e.g. the Manusmriti) that claimed varna was central to the organization of society These texts also reconfigured the ideology of varna to relate it to ideas of PURITY and POLLUTION They also reinforce the idea of VARNASHRAM DHARMA, that it is the spiritual and moral duty of each varna to fulfill its given role in society (Kshatriyas to fight/rule, Sudras to serve) Those who refuse to acknowledge this, or violate varna prescriptions deemed to be OUTSIDE the varna system, or Out-caste The same prescriptive texts also reinforce PATRIARCHY and reinforce the subordinate positions of women of all varna to men of their families

Varna and Political Power From the very beginning varna and political power closely linked Upstart kings patronized Brahmins, who fabricated genealogies to represent these rulers as true Kshatriyas Gupta rulers, under whose patronage many of the dharmashastras were compiled, were of Vaisya origin Varna ideology also useful for absorbing many waves of migrants and conquerors. Some historians believe that 6thCentury Hun invasion s leaders given Kshatriya status, and rank and file lower varna status Indian encounter with a young and vibrant Islam in the 8th to 11th centuries was the first one where new rulers did not accept the hierarchal ideology But varna remained a component of political power at local levels, well into the 18th Century However, varna was, till this time, recognized as closely connected to POLITICAL and not RITUAL power/status. Many examples of Shudra kings

Colonial Construction of Caste System British rule had a profound impact on how we understand caste today British administrators and scholars (called Orientalists) represented caste as fundamentally different from other hierarchical ideas Understood caste only from Brahmanical TEXTUAL sources (dharmashastras), and therefore as Hindu religious ideas and not power Allowed for the othering of the colonized, making them exotic, different, and most important, in need of Western, enlightened, rule Policies and Laws based on this idea, Census and Elections e.g., reinforced this idea of caste, made it a LIVED reality for Indians. Colonial education taught this notion of caste to generations of Indians Caste reified. Even created entities such as criminal and martial castes Patriarchy was reinforced, largely on account of believing dharmashastras to be religious laws governing a religious people Overall, created a much greater FIXITY in ideas and practices around varna- jati

Colonialism and the language of rights Paradoxically, colonialism also created a limited space for the articulation of rights by lower caste groups Attempts at creating a systematic ordering of all jatis into the same varna led to thousands of petitioning challenging colonial ordering Some jatis claimed higher varna status based on the purity of their customs, that often also included the greater seclusion of and restrictions upon women of these jatis Others such as Jyotiba Phule s SATYASHODHAK SAMAJ attacked the very foundation of the hierarchical principle of caste This encourages creation of SUPRA LOCAL identities based on colonial understanding of Varna-Jati but VERY DIFFERENT from the much more localized sense of identity that had earlier been the case Urbanization and new occupations also undermined the traditional economic basis of jati rankings

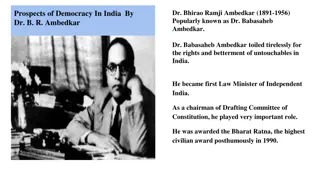

Caste and Nationalism Most nationalists were upper caste men, and imagined the nation in those terms Most secular/liberal Nationalists, ALL Hindu nationalists, even many Communist leaders were Brahmin men Their vision WAS challenged, in the 19th century by leaders like Jyotiba Phule, and in the 20th by a variety of anti-Brahmin movements, many committed to smashing of the caste system all together Gandhi and Ambedkar represent this division most starkly Gandhi initially accepts VARNASHRAM DHARMA as a harmonious system of interdependence. But criticized the practice of UNTOUCHABILITY, termed untouchables Harijans or Children of God Ambedkar found Gandhi and elite nationalists representations to be patronizing. Wanted to smash the caste system rather than reform it. Organized untouchables politically, and termed them Dalit (the broken or oppressed)

Caste at Independence Constitution 1950 Single most far reaching and revolutionary change, equality of all citizens Ambedkar played important role in shaping the draft Affirmative action policies (reservations) for Dalits, to compensate for historically enforced deprivation Liberal Cringe/ Modernization As products of colonialism, most liberals, including Nehru, were embarrassed about caste, and wished to avoid foregrounding what they saw as a sign of backwardness As upper caste men themselves, they never faced the inequities of caste discrimination Hoped that caste would simply disappear with modernization, though electoral politics demanded the inclusion of lower caste groups in the political process Ambedkar and Nehru Some commonalities in approach, both committed to social justice and creating a level playing field for all Indians But Ambedkar was very clear that caste needed to be tackled head-on rather than ignored in the hope it would disappear Disagreement over Hindu Code Bill. But even legislation passed piecemeal, a huge step, allow for intercaste marriage, divorce, and equal rights for wives, sisters and daughters of a Hindu family Ambedkar remained disappointed and signaled this through a public renunciation of Hinduism and conversion to Buddhism shortly before his death in 1956 Hindu Right Leadership entirely upper caste Brahmins Did NOT support affirmative action for Dalits Opposed Hindu Code Bill

Caste and Class (Economic Power) Overlap between class and caste. Caste often determined: Access to land Access to education Access to valued skills or commodities When jatis with traditional lower varna status had these, they could and did exercise power, and some sought higher varna status E.g. Marathas in the 18th C western India, Nadars of southern India in the early 20th C Could also link the later rise of middle peasants and OBC to their increased economic power Dalits (along with tribal groups), remained excluded from significant economic gains in the colonial era; they were labor, very rarely landowners and often confined to the most degrading and servile occupations. This was one reason why affirmative action programs were initiated only for Dalits in 1950

Caste and Politics in Independent India Success of Nehruvian era premised on the Congress System where an English-speaking upper caste elite acted as patrons of locally powerful backward caste clients (Sheth, 112; Yadav, 12-14) This elite was for most part uncomfortable with caste identities, and a very peculiar caste-class linkage was forged in which the upper castes functioned in politics with the self-identity of a class (ruling or middle ) and the lower castes with the consciousness of their separate caste identities (Sheth, 112) Post Nehru, and premised on economic gains made in earlier decades, these lower caste groups no longer willing to be clients The emergence of regional parties in the 1960s such as DMK in Tamilnadu, or the Bharatiya Kranti Dal (BKD) in UP and Bihar, were as much an expression of lower caste assertion as regional interests

Political Caste Changing meanings of varna linked to power historically and in the present Caste-based politics today, with labels such as forward and backward as well as horizontal alliances between different caste- based identities have virtually nothing to do with ritual status, purity and pollution, etc., but everything to do with modern forms and necessities of electoral politics This became most apparent at the national level of politics in the post Mandal era The older upper class elite (terming itself middle class) resisted what they derisively called the Mandalization of politics, their opposition had the opposite effect, and resulted in radical alterations of the social bases of politics in India (Sheth, 113) OBCs were here to stay, and became a mainstay of Indian politics

Dalits in Post Independence India Everyday forms of discrimination: Bama Faustina s Scorn shows how despite legal equality and reservations, everyday forms of discrimination (and of course economic dependence) excluded, humiliated, and exploited Dalits in everyday interactions Dalits remain among the poorest, most marginalized and exploited groups in contemporary India Gender: Not only did caste values direct gender roles, lower caste women, particularly Dalit women bear the double burden of caste and gender inequality Education: Perceived as one avenue of escape for Dalits, especially after reservation of seats in government institutions of education Jobs: Reservations provided some jobs, but pervasive everyday forms of discrimination made political mobilization necessary The Congress System operates with Dalits too in the Nehruvian era, though with less success on account of the Ambedkar legacy Breakdown of the Congress system exemplified by the BAMCEF: In 1978 Kanshi Ram forms the Backward And Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF) to organize and mobilize the Dalit and Backward Employees in government service Access to a degree of economic power and social status leads to the formation of the BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY in 1984. This Dalit political party today led by Ms. Mayawati, a Dalit woman, who has already served twice as Chief Minister of India s largest state

Caste and Contemporary Politics A range of lower caste political mobilizations ended the upper caste hegemony over Indian politics At best, national (aka upper caste) parties had to negotiate directly with lower caste sociopolitical collectivities who were no longer content with proxy representation by the upper caste, middle class elite, they wanted power for themselves (Sheth, 114) The BJP tried, initially, to deny the importance of caste in favor of a Hindu community, political reality has forced them to address caste by highlighting the OBC-ness of Narendra Modi, or attempts to appropriate Ambedkar to their agenda At the same time, although OBC and Dalit castes form the majority of the country s population, structural contradictions and a history of hierarchical relations prevent the sort of unity hoped for by Kanshi Ram Caste has proven to be both a force for greater political inclusivity, yet also prevented the consolidation of India s subordinated population

Caste Reconsidered Far from an unchanging system, the history of caste is one of incredible change From Varna to Jati, from Vedas through Buddhism to the dharmashastras; from colonial reifications to the formation of supralocal identities, to the mobilization along caste lines to challenge elites in power The history of caste is a history of power, a history of politics The ideologies and practices related to caste are used to suppress, to impoverish, to marginalize and to dehumanize At the same time, history also shows how caste can and has been used to challenge status quo, as it has in the short period since independence