The Evolution of Bourgeois Politics in 17th Century England: Insights from Hobbes and Locke

The emergence of bourgeois politics in 17th century England marked a significant shift in power dynamics as capitalism began to take hold. The bourgeoisie initially allied with the monarchy to overthrow the feudal order but later turned against the royal power. The Puritan Revolution and the Glorious Revolution were key events during this period, signaling the rise of the capitalist class. This era also saw the development of Hobbesian political theory, which laid the foundation for modern systematic political thought by addressing fundamental questions about the state, government, and societal loyalty.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

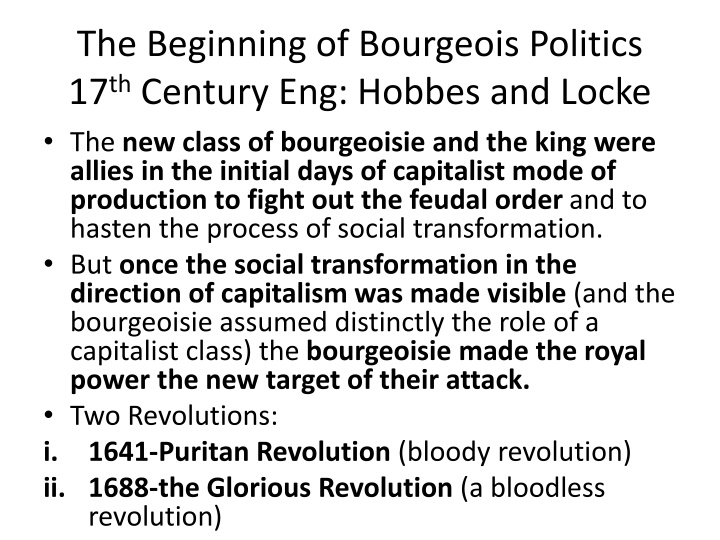

The Beginning of Bourgeois Politics 17thCentury Eng: Hobbes and Locke The new class of bourgeoisie and the king were allies in the initial days of capitalist mode of production to fight out the feudal order and to hasten the process of social transformation. But once the social transformation in the direction of capitalism was made visible (and the bourgeoisie assumed distinctly the role of a capitalist class) the bourgeoisie made the royal power the new target of their attack. Two Revolutions: i. 1641-Puritan Revolution (bloody revolution) ii. 1688-the Glorious Revolution (a bloodless revolution)

The Puritan Revolution The Puritan Revolution in England really began with the convening of the Long Parliament in Nov, 1640 (long because not dissolved for 12 years). Puritans were a band of religious dissenters who were in majority in the Parliament. Beneath the veneer of their spiritual enthusiasm there lay a distinct class interest. So Puritan Revolution was the first successful bourgeois revolution in England. 1588- Spanish Armada-England s victory over Spain and the initial consolidation of the English bourgeoisie was completed by 1588. This signified the role of English merchant class English naval power.

Hobbesian Approach to Politics Hobbesian approach to politics was derived from Machiavelli and the core of his theoretical content was drawn from Bodin. With his secular approach to politics Machiavelli took care of the perspective of bourgeois political theory but failed to furnish with a proper content. By formulating a theory of the state and by giving focus on sovereignty as the fundamental ingredient of the state it was Bodin who sought to fill this gap and thus pointed the direction in which future political theory would evolve. But the corresponding problem of political obedience a neat solution of which might alone place the sovereignty of the state on a firmer foundation somehow escaped his attention. Hobbes steps in here.

Hobbes Fundamental Issues of Politics Following Machiavelli he placed politics on a materialist foundation and then went on to theorize not simply on the bourgeois man but on the bourgeois society as well. Hobbes revived the Aristotelian tradition of dealing with the fundamental issues of politics. It can rightly be argued that modern systematic political theory, indeed, begins with Hobbes. He deals with things strictly political and furnishes well-reasoned answers to questions that have ever remained vital issues in the province of politics.

Hobbes Fundamental(contd.) Why do people at all need state and government; What again is the basis of their functioning; and, further, Why and how people living under the state and government are to remain loyal to them are the three fundamental questions that receive most of Hobbes attention. For answering these questions Hobbes turns neither to theology nor to history. Indeed, he chooses to rely on hypothesis. This hypothesis is about the state of nature- a condition that, he feels, alone explains the emergence of civilized society and government and the basis of their working.

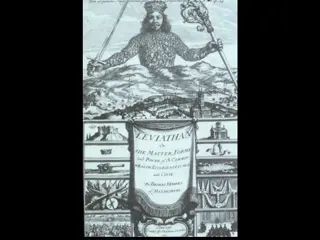

Hobbes Methodology-Hypothetical State of Nature Civilized state and government came into existence due to a deliberate human choice expressed through the making of the contract. The people are obliged to give the sovereign authority their unconditional and perpetual obedience. But on the other hand, the sovereign authority is free to exercise an unlimited power, others having no right to curb it. Law is nothing but his formal command. The sovereign alone has the right to make and repeal laws, but he himself is very much above it.

Hobbes Methodology(contd.) The whole of Hobbes political theory rests upon his assumption about a set of conditions prevailing in the state of nature. Since he takes the state of nature as nothing more than a logical hypothesis necessary for constructing his political theory Hobbes does not care for its historicity. It has only methodological uses for him. Hobbes philosophy was influenced by both Galileo (Law of Uniform Motion) and Euclid (47th Proposition). So a synthesis between contemporary scientific knowledge and traditional geometrical method. This explains Hobbes reliance on the state of nature as a useful step toward an understanding of the nature and necessity of society and government.

Hobbes Axiomatic Method: A Methodological Base of His Philosophy The axiomatic method in geometrical reasoning-the method of starting from self-evident assumptions to arrive at knowledge that is far from self-evident- appealed to him. Thus, he decided to make this axiomatic method a methodological base of his philosophy in so far as he was left convinced that to know a thing it is necessary to begin with some non-verifiable hypothesis. After setting the methodological base Hobbes proceeded to formulate his philosophical principles by making a good use of Galileo s law of uniform motion.

Hobbes Materialistic View of the Universe Hobbes rested his philosophy on a materialistic view of the universe. The whole mass of things in the world represented matter alone and Hobbes chose to look at this matter in terms of Galileo s law of uniform motion. An object in motion would stay in motion perpetually until something else stopped it. We are capable of knowing a thing just because it is set in motion. Objects in motion around us strike our sense organs and cause further motions within us. It is these internal motions that we perceive as sensations which, again, are the source of our knowledge.

Hobbes Doctrine of Causality Hobbes doctrine of causality is another important component of his philosophy which follows from Hobbes theory of motion. If the knowledgeable world is in motion, then certainly it has its before and after (cause and effect) and every after represents a movement away from its before and, therefore, is invariably an effect of the latter. Therefore, his hypothesis- the state of nature is not anything accidental or erratic but it actually logically follows from his laws of motion, his doctrine of causality and his axiomatic method.

Cause of Human Society and State To know/identify the cause of human society and state history does not help very much in locating the point at which the society and state of man came into existence. Hobbes cannot take shelter in theology because of his materialistic view. He cannot take help from metaphysics either. As under the influence of geometry he has already taken axiom as the important instrument of knowledge Hobbes clings on to the hypothetical state of nature.

A Revolution in Western Politics Hobbesian theory constructed on the foundation of this state of nature brings in a revolution in Western politics. There are several reasons for this to be termed a revolution. i. In the first place, Hobbes rejects outright the theological or metaphysical foundation of politics. He rejects the theory of divine rights and states without any ambiguity that man s society, state and government are all his deliberate creation for his own convenience. ii. Secondly, at Hobbes hands politics for the first time, becomes a science. Politics is not merely given a purely secular character but a scientific character as well (good use of scientific assumptions).

A Revolution(contd.) iii. Thirdly, in Hobbes theory politics is clearly given a rational foundation (triumph of human reason). To him the emergence of society and state means a triumph of human reason. Society and state are shown to be the result of a contract. Although it was a contract made by frightened human beings they could make it possible just because they chose to obey the dictates of reason. Society without this reason means chaos and destruction. For Hobbes reason, ultimately, is the arbiter in politics.

The Question of Authority and Obedience It is very important that long after Aristotle, Hobbes again picks up the question of authority and obedience as the core problem of politics and treats it in a way hitherto unknown in European political thought. He feels that in the interest of stability and permanence of the social order, the most important thing needed is absolute political sovereignty and he derives its rationale not from any moral, religious or metaphysical argument, but strictly in the light of what he considers to be the bare facts of life. Here Hobbes argument is that the state will be all- powerful and subjects must gracefully submit to it just because this submission happens to be the price of their orderly civilized living.

Prudential and Rational Political Obligation It is naturally a kind of political obligation based on considerations of expediency and hence it is clearly a prudential political obligation in view of the fact that the disadvantages of disobedience are too great to bear. Yet it is a rational obligation in that it is not out of any momentary impulse, but as a result of a well-reasoned calculation. But, in any case, it is not a moral obligation of the type envisaged by Aristotle for, unlike the latter, Hobbes never suggests that obedience to authority is meant to bring one s moral improvement.

A Moral Obligation by Implication Arguments may, however, be stretched to show that Hobbes obligation is, by implication, a moral obligation as well. For instance, if conditions of civilized living are taken to be the necessary prerequisites for man s moral betterment, then, Hobbes sovereign ensuring these conditions must be viewed as an instrument of moral progress and in that case obedience to this authority may be shown to be determined by a moral cause. But, no matter whether it is a prudential or moral obligation, the fact remains that Hobbes very seriously takes the problem of political obligation and tries to give a clear and unambiguous answer to this question.

Absolute Sovereignty Hobbes realizes that to talk about absolute sovereignty is not enough. It is also very important to devise suitable means through which this idea of absolute sovereignty may be given effect to. That is why he conceives of law as nothing but the command of the state and puts the sovereign authority much above this law. Hobbes is convinced that an orderly society thrives mainly on political control which has to be stabilized by making citizens obey laws without grudge and grumble as their duty. And, lastly, it is the intention of Hobbes to show that the whole political arrangement is not arbitrarily imposed by those who control it, but is rather the result of a careful choice exercised by those who submit to it.

Absolute Sovereignty (contd.) In other words, his point is that the state, by nature, is formidable political authority. By nature, it is all-pervasive. But, then, they work just because people living under them have voluntarily consented to have such things. In this way, Hobbes tries to effect a marriage between force and consent.

Hobbes State of Nature: More than a Methodological Tool On a careful observation it can be noticed how the state of things as assumed to be prevailing in the state of nature virtually reflects the conditions of the bourgeois society in its early phase of development. The man as depicted in Hobbes state of nature is essentially a bourgeois man frantically looking for glory and gain at any cost, driven solely by the lust for power and by the fantastic appetite for material achievements. A society comprising such egoistic individuals must be a society marked by fierce competition and struggle that, in the long run, might threaten its very survival.

Hobbes State(contd.) In the bourgeois society relations between men were determined by the impersonal relations of the market and, therefore, were much more complex. Unless these complex market relations were adequately regulated they might bring in anarchy as there was lack of a built-in order and harmony in the capitalist society during this initial phase. Hence the bourgeoisie in the early phase needed a sovereign state to impose regulations whereby their own operations might assume a distinctly orderly shape. Thus, by means of his political theory, Hobbes was trying to give a carefully devised political advice to the contemporary bourgeoisie to grow only under the supervision of a sovereign state. But while he emphasized the need of political control he, however, could not spell out on questions like who and in what manner would wield this political control.