Rationality in Science, Religion, and Everyday Life: Exploring Belief Formation and Rational Decision-Making

Explore the essence of rational belief formation across science, religion, and daily life through the lens of cognitive processes, decision-making, and value systems. Delve into the conditions for rational belief, practical decision-making, and axiological rationality to understand human cognition and actions. Discover the intersection of theory acceptance and refutation in science, existential experiences in religion, and the prevalence of beliefs in everyday life.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Rationality in Science, Religion, and Everyday Life Part three of MA Course Knowledge, Rationality, and Society Emanuel Rutten

Literature and Schedule Literature Mikael Stenmark, Rationality in Science, Religion, and Everyday Life (University of Notre Dame Press: Indiana 1995), Chs. 1-10 Schedule Tue Nov 25: Chs. 1-3 Thu Nov 27: Chs. 4-5 Tue Dec 2: Chs. 6-8 Thu Dec 4: Chs. 9-10 Links to Slides & Questions Twitter: @emanuelrutten

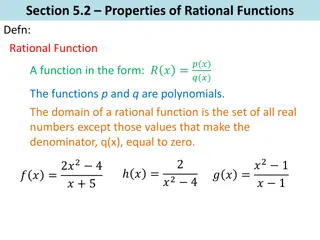

Belief formation, revision and rejection Part of being human is to have the ability to form, revise and reject various believes. Our cognitive capabilities include belief regulation processes When it is that people form, regulate and reject their believes in a proper, responsible, or reasonable way? What are the conditions for rational belief? Are these conditions the same for all areas of human life (science, religion, everyday life, etc.)? Are they the same for all cultures? And for all times? In order to identify these conditions we have to clarify what rational belief actually is, and whether it is the same for all areas of life, cultures and times The notion of rationality does not apply only to beliefs. Human decisions and actions can be rational or irrational as well. Yet, our focus is on belief

Science, religion, and everyday life Science is taken by many as a paradigm example of rationality. Any model of rationality must deal with theory acceptance and refutation in science Religion originates in existential experiences of joy and suffering, meaning and alienation, guilt and liberation, etc. We may ask what the conditions are for reasonable beliefs about the ultimate, the absolute, the sacred Everyday life is not an optional area and in it we have clearly the most of our beliefs. It is therefore also a paradigm case for models of rationality

Theoretical, practical and axiological rationality What kinds of things can be rational or irrational? Beliefs, decisions, actions, behaviors, evaluations, plans, strategies, people What kinds of things are typically a-rational? Trees, planets, cars, phones, tables, chairs, taste (e.g. pizza, ice-cream), art There are three areas where we can decide what to do. But then there are three contexts of rationality (Rescher) Theoretical rationality is about what we should believe or accept o Practical rationality is about what we should do or perform o Axiological rationality is about what we should value or prefer o Axiological rationality is required since decisions of people can be rational only in case the ends or aims they try to achieve is in their real interest

Axiom of reasonable demand Rationality has to be realistic in the sense that it cannot require more than what the supposed agent can possibly be expected to do (given the agents actual resources and circumstances or constitution and predicament ). In short: ought implies can (Kant) Yet, many models of rationality are about perfect agents. They introduce agents as purely theoretical abstract constructions (ideal epistemic beings) Therefore, many models of rationality are too idealized or utopian to apply in an interesting and relevant way to actual limited human beings like us They imply that we are usually irrational in most things we do, which is an absurd consequence. Models of rationality must take into account what we as real human beings can reasonable do and what is not in our power to do

Three ways to construct models of rationality But are empirical aspects to be taken into account when proposing models of rationality? Is it not enough to focus on strictly conceptual and logical matters? (This question can in fact be asked of any philosophical issue) There are three philosophical methods (for creating models of rationality) The formal approach o The practice oriented approach o The contextual approach o The first and third are situated at each side of a spectrum. The second is an inter-mediating position between both extremes

The formal approach (purely a priori) Formulation of a model of rationality can be done wholly independently from the actual practices by applying strikt conceptual and logical tools Pure conceptual and logical enquiry has complete authority over the practices themselves. The actual practices are strictly speaking irrelevant The constructed model of rationality has to be appropriate for any reasonable being and no matter what practice this being is involved in In fact, the constructed model of rationality has to apply for all possible worlds, that is to say, no matter what the world is like No examination of (the history of) a practice is required to recommend an adequate model of rationality for that practice. One model applies to all Practices that do not satisfy the pre-established universal and ahistorical model (standards, criteria) for rationality are refuted as being irrational

The contextual approach (purely empirical) Formulation of a model of rationality is totally dependent on the actual practices. Only an examination of these practices is needed. Nothing else The actual practices constitute themselves the only justification for what is and what isn t rational within them. External criteria are wholly rejected Contextualists merely explicate the standards of rationality that are already given within the actual practices. They are their own ultimate authority The standards for rationality are thus wholly internal to the actual practices. They are in other words practice-determined The standards for rationality can and do in fact significantly differ between the various actual practices (such as between science and religion) Even the nature of rationality (the very meaning of rationality) likely differs between practices. Rationality just is not the same for all actual practices

The practice-oriented approach (both) There is a basis independent of each practice from which we can assess its rationality and propose rationality criteria for it (contra contextualism) It is possible to critically establish from a purely philosophical point of view, from the outside of a practice, standards of rationality for that practice Yet, it is required to have substantial contact with each of the practices. We must take into account its aims, activities and situation (contra formalism) The proposed model of rationality for a practice can only be relevant for a practice if we understand its means and ends. Its function and nature We must be sensitive to what is going on in a practice, what one tries to achieve and what is achievable. This places constraints on proposed models The proposed standards for rationality can and do in fact differ between various actual practices. Yet, its very nature or meaning is likely universal

Rationality and religion A key issue is the applicability of rationality to religion. In order to address this topic properly we need to extend the scope, namely to the applicability of standards of rationality to both religious and secular views of life The discussion of the rationality of religious belief is not only about whether religious belief meets the criteria or standards of rationality, but also about what standards of rationality are the approprate ones to use in this context The goal here is not to establish whether some view of life is rational, but to identify the proper standards for assessing the rationality of views of life Various models of rationality are investigated in order to assess which of them is the most appropriate to use for religious belief. We thus examine the conditions for a discussion on the rationality of religious belief One option is the scientific challenge to religious belief. It has it that all religious beliefs must conform to the rationality standards of science A related challenge is evidentialism. It has it that religious beliefs are rational only to the extend that there is sufficient evidence for them

Models of rationality A model of rationality consists of [i] an account of the nature of rationality together with [ii] an account under what conditions something is rational (the standards or criteria of rationality) The following models can be distinguished Formal evidentialism There is one nature of rationality and one set of standards for rationality. This model is related to the formal approach o Social evidentialism There is one nature of rationality but different standards for different practices. This model is related to the practice-oriented approach o Presumptionism There is one nature of rationality but different standards for different practices. This model is related to the practice-oriented approach o Contextualism There are different natures of rationality and different standards for different practices. This model is related to the contextualist approach o For social evidentialism and presumptionism one sometimes says that there is one set of standards (because standards here are still structurally similar)

The Nature of Rationality Wat is rationality? What does it mean to say that something is rational? Is it possible to provide a general characterization of rationality? Without an answer to this question it will be difficult or even impossible to identify proper standards (criteria, conditions) for when a belief or action within a certain practice is rational But is there a single meaning of rationality? Perhaps rationality has different meanings in different domains? In that case it isn t univocal Descriptive incommensurability thesis Rationality has different meanings in different domains o Normative incommensurability thesis Rationality should have different meanings in different domains o

Four different aspects of rationality We mentioned rationality snature and standards. But there are four aspects The nature of rationality What is rationality? What is its meaning? o The standards of rationality What are the conditions for being rational? o The reasons of rationality What may count as rational evidence? o The aims of rationality What are the ends or goals of rationality? o The difference between standards and reasons can also be understood as a difference between generic and detailed standards. If a practice-oriented philosopher holds that standards may change between practices, he or she acutally means the detailed standards and not the generic ones Examples of (generic) standards One must always have sufficient evidence for one s beliefs (evidentialism) o One may hold-on to one s beliefs as long as they aren t refuted (presumptionism) o

Four different aspects of rationality What counts as rational reasons in one practice (e.g., religion) may not count as rational reasons in another practice (e.g., science) because these practices may have different aims. (Thus the fourth aspect is actually about practices) Moreover, differences in rational reasons between practices do not always entail differences in standards between practices. And differences between standards between practices do not always entail differences in nature When we ask for the nature, standards, reasons and aims of rationality, we refer solely to normative rationality and not to generic rationality Generic rationality refers to the capacity for reasoning. An agent has generic rationality if it has the resources of reason. It thus can be rational or irrational. An entity without generic rationality is a-rational. It cannot be rational or irrational o Normative rationality An agent having generic rationality is normatively rational (hereafter: rational) just in case it excercises its reason properly or responsibly. A belief or action is normatively rational if and only if it is or can be justified o

Deontological rationality Any characterization of the nature of rationality needs to take into account that rationality is a normative concept ( ought to ) and a term of appraisal ( positive attitude, approval ). One way of characterizing it is deontological According to the deontological account rationality consists in the fulfillment of certain duties (responsibilities, obligations) in respect to what one is doing (e.g., believing, acting). In the context of belief ( theoretical rationality ) these responsibilities are called epistemic responsibilities. It leads to an ethics of belief The epistemic duties are prima facie and not ultima facie. They can be overridden by other non-epistemic duties in special circumstances But what do these duties consist in? This brings us back to the level of (generic) standards of rationality. Examples include evidentialism (never belief things without good evidence for their truth) or presumptionism (one may hold-on to beliefs provided there is not sufficient counter-evidence)

Means-End rationality Another characterization of the nature of rationality is means-end rationality. According to it rationality consists in the efficient pursuit of given ends. There is thus nothing that is rational per se. Rationality is always goal-relative Rationality is about how to achieve our aims as efficient as possible. It does not tell us what these aims should be. It is about means and not about ends To assess whether a certain decision is rational, we not only have to know people s goals, but also their resources and situation (r- and s-relativity) According to the objective account of rationality what we do is rational if it is probable that it will satisfy our goals in an efficient manner According to the subjective account of rationality what we do is rational if it seems or appears to us probable that it will satisfy our goals efficiently In that case rationality becomes also relative to the information had by the agent

A puzzle concerning rationality John has been in a state of severe anxiety for years now. Recently he obtained strong evidence that he is going to die if he does not get rid of his anxiety. He also has strong evidence that the only way for him to acquire peace of mind is to believe that the universe will exist forever. Suppose that John has sufficient evidence for the claim that the universe will not exist forever. Still, in an ultimate attempt to save his life he starts to try to force himself psychologically to believe - contrary to the evidence - that the universe will exist forever. After two weeks he finds himself in a state of believing that the universe will exist forever. As a result he obtains the desired peace of mind and thus loses his anxiety. In this way he manages to save his life. Now, is John's belief that the universe will exist forever rational?

Can both characterizations be combined? The characterization of theoretical rationality as an epistemic duty does in fact assume a goal: to believe many truths and eliminate many falsehoods But then the deontological characterization for theoretical rationality can be reprashed as follows. People have the responsibility to pursue efficient means for satisfying their epistemic goals In addition to epistemic goals there are also non-epistemic goals (such as well-being and survival). Epistemic rationality involves only epistemic ends and non-epistemic rationality involves only non-epsitemic ends Are usefulness, simplicity and predictability epistemic goals or not? Note that epistemic rationality is not the same as theoretical rationality and that non-epistemic rationality is not the same as practical rationality (why?) The deontological and means-end notions of rationality can be combined: We have a duty to pursue our epistemic and non-epistemic goals efficiently Science and religion have complex (both epistemic and non-epistemic) ends

Some Examples Mary believes in quantum mechanics because she thinks that there is good evidence for its truths and her aim is to get in touch with reality This is an instance of theoretical and epistemic rationality John believes that the universe will exist forever because it gives him peace of mind and his aim is to get peace of mind This is an instance of theoretical and non-epistemic rationality Brigitte performs a daily walk because it helps her to get new research ideas, which is very important for her since she wants to study the world This is an instance of practical and epistemic rationality Dave engages in sports at his university because it keeps him healthy, which satisfies his goal of well-being This is an instance of practical and non-epistemic rationality

Epistemic and non-epistemic reasons What these examples show is that we can have epistemic and non-epistemic reasons for what we believe or for our acts because we can have epistemic and non-epistemic ends for believing and acting A good epistemic reason for a belief or act connects the belief in an appropriate way to the epistemic goals that are presupposed (e.g. believing only truths) o A good non-epistemic reason for a belief or act connects the belief in an appropriate way to the presupposed non-epistemic goals (e.g. peace) o If the goal is complex (i.e., consists of both epistemic and non-epistemic ends), agents are to take into account epistemic and non-epistemic reasons

Towards a holistic rationality The combined notion of rationality ( a duty to establish efficient and sufficient means for our ends ) is still too narrow. For the assessment of appropriate ends is still out of scope. It is still only about means Our only duty is to find efficient means for whatever we want. Reason does not tell us where to go, it only tells us how to get there. It is the slave of the passions (Hume) Such a limited conception of rationality goes strongly against our intuitions. How could someone who efficiently chooses his or her total ruin be rational? We thus need to be able to rationally assess and choose our goals as well Plausibly, meaningless, worthless or destructive ends are not rational. Ends that are not in people s real or best interests are not rational either. And the same holds for ends that are contrary to our real needs Reasoning about ends is thus closely related to reasoning about values and preferences. We therefore need to bring in axiological rationality

Towards a holistic rationality On a more inclusive conception of rationality a rational person has a duty to choose appropriate or valuable ends (ends that are in his or her best interest) and to find sufficient and efficient means to achieve them But phrased in this way, the conception is still too narrow. For efficient means that are destructive, contrary to our real needs or contrary to our best interests are not rational either. Our means must also be appropriate The axiological dimension is thus relevant for our ends and our means On the holistic conception of rationality we have a duty to choose valuable or appropriate ends (ends that satisfy our real needs) and to find sufficient, efficient and appropriate means for achieving these ends The holistic conception of rationality has both a theoretical-practical side or dimension (conditional: establishing proper means-end connections) and an axiological dimension (categorical: establishing appropriate or valuable ends)

Chapter 3: Science and Formal Evidentialism

The formal approach to scientific rationality The best place to start for introducing formal evidentialism is with science since most if not all adherents of formal evidentialism take science to be the paradigm of rationality. So let s look at how formalists view science The formalist holds that philosophy of science is the study of the logical properties of and the logical relations between scientific propositions or collections of propositions (theories). It is primarily logical analysis The idea is that there is a logic underlying the methods of science and the task of the philosopher of science is to explicate this logic a priori Logicality thesis: The rationality of science amounts to a logical system There is no need to study actual scientific theories. Simple generalizations like All swans are white properly represent the logical structure of theories According to this view philosophy of science is the study on how a rationally ideal scientist should proceed and what he or she should rationally accept

Scientific evidentialism The first requirement is that science demands sufficient evidence (e.g., correspondence to empirical data) for all theories it accepts Accepted theories should be accepted with a firmness proportional to the probability assigned to it on the basis of the available evidence It is not what the man of science believes that distinguishes him, but how and why he believes it. His beliefs are tentative, not dogmatic; they are based on evidence, not on authority or intuition (Russell) The first part is thus an acceptance of evidentialism: It is rational to accept a theory only if, and to the extend that, there is are good reasons to believe that it is true. It consists of two principles The evidential principle: It is rational to accept a proposition only if there are good reasons (or evidence) to believe that it is true o The proportionality principle: The firmness with which a proposition is accepted must be in proportion to the strength of the evidence for it o

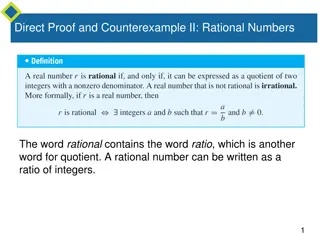

Scientific evidentialism But were to start? Typically, it is claimed to start from singular observational claims such as At time t and place p event e occured or There is a tree in front of me . But how to jump from these to the universal claimsof theories? Besides, according to the evidential principle scientists must also provide evidence for their observational beliefs. In fact, they must provide evidence for that evidence as well, and so on. So an infinite regress seems unavoidable To prevent such regress the general character of the evidential principle must be given up. We need to distinguish between non-basic or derived beliefs (in need of evidential support of other beliefs) and basic beliefs (that do not need evidential support of other beliefs). This is called foundationalism Observational beliefs are then taken as basic ( foundational ). In fact, it is not even possible to provide non-circulair evidence for it (why?) Revised evidential principle: It is rational to accept a non-basic proposition only if there are good reasons (or evidence) to believe that it is true

Foundationalism The relation between our beliefs is asymmetrical. The inferential justification goes only from basic beliefs to non-basic beliefs. Further, belief A constitutes evidence (or a reason) for belief B only if it is more basic than B Foundationalism differs from coherentism (that does not distinguish basic from non-basic beliefs) Although basic beliefs do not need evidence, they are not groundless. They can be justified. But this justification is non-inferential or immediate (e.g., rests on sense experience) What types of beliefs count as properly basic? Strong foundationalism holds that basic beliefs should be immune to doubt. They are thus either self-evident (1+1=2) or incorrigible (I am visually aware of green ) o Weak foundationalism holds that basic beliefs must be highly likely true. They are self-evident, incorrigible or evident to the senses (There is a tree in front of me) o Some philosophers (e.g., Plantinga) go further and also allow for example memory beliefs as basic. In this and previous case basic beliefs are defeasible o

Foundationalism Fallibilism is the view that all our beliefs might be wrong. Foundationalism is not to be contrasted with fallibilism (since weak foundationalists are in fact fallibilists) but with coherentism (no distinction basic and non-basic) (a) a properly basic belief, or (b) can be inferentially supported by properly basic beliefs or other already derived non-basic beliefs; and (c) the strenght of the non-basic beliefs are proportional to the support from the foundation According to foundationalism a belief is rational only if that belief is either Evidence refers to inferential justification of a non-basic belief. Evidence for such a belief refers to inferential justifiers for it, i.e. the belief is inferentially supported by other beliefs. Sense experience and memory are examples of non-inferential justifiers for basic beliefs (these justifiers are called grounds) The experience of snowing non-inferentially justifies the belief that it is snowing The belief that John is abroad can be inferentially justified from other beliefs

The rules of science How can we justify the step from singular observational statements to the general claims of scientific theories? According to the formalists there are scientific rules ( the logic of science ) for rational theory choice Scientific rationality is rule-governed or -determined. It s about rule-following Similar to Frege sdeductive logic formalists aimed to establish an inductive logic for rationally assessing, comparing, accepting and refuting theories given the available observational data Formalists knew that due to the induction problem scientific theories cannot conclusively be verified by the available empirical evidence. So, inductive logic will not be able to infer theories with absolute certainty from observations Therefore, acceptable inductive arguments need to show only that the conclusion (e.g., the theory under consideration) is probable given the evidence. And the inductive logic must enable the scientist to calculate a priori precisely the probability of the theory being true given the data

Bayesianism According to the formalists inductive logic has full authority, not scientific practice. Today s dominant model of inductive logic is developed by Bayes Scientists are ideal agents (Bayesian agents) that compute the probabilities of their hypotheses being true (given the evidence) by using Bayes theorem (which can be derived from the axioms of mathematical probability theory) P(e|h & k) P(h|e & k) = x P(h|k) P(e|k) P( ... | ) stands for The probability that given h is the hypothesis (theory) under consideration e is the available empirical evidence Objective (Subjective) Bayesianism takes the priors to be objective (subjective) k is the background knowledge P(h|k) is called the prior probability ( the prior ) P(e|h &k) is called the likelihood The ratio is called the explanatory power

Poppers logic of conjectures and refutations Popper famously rejected any attempt to develop an inductive logic. We should not try to support theories (general claims) with observations. But he agrees that science has a logic and is about following rules Popper is thus a formalist because he accepts the logicality thesis He proposes the following logic. Evidence should only be used to refute or falsify theories. This requires only deductive logic since e.g. All swans are white is deductively refuted or falsified by one observed black swan Scientists need to conjecture refutable or falsifiable theories and actively seek evidence that refute or falsify them. Once a theory has survived several falsification attempts (tests) it is corroborated and can be rationally accepted Like all formalists, his account of scientific method is intended to be universal and ahistorical. He thus accepts the stability thesis of formalism, namely that the rationality of the scientific method is invariant over time and domain

The rule principle Formalists accept the rule principle according to which all rational beliefs (and actions) must be arrived at by means of appropriate rules Rules help to establish logical or necessary connections between propositions o Rules help to infer and refute theories from available evidence (observations) o Rules help to reduce or even eliminate arbitrariness ( predictable outcomes ) o Rules limit room for diverging conclusions ( universal or objective outcomes ) o Rules can be applied in any possible context ( practice independence ) o Rules ensure that conclusions folllow necessarily from the available evidence o Rules ensure an outcome in a finite number of steps ( algorithm ) o Rules application requires no detailed knowledge of the content ( formal ) o

The formalists conception of rationalitys nature Both a deontological and a means-end conception of rationality can be found among formal philosophers of science With respect to the deontological side scientists have intellectual duties (e.g., only accept theories supported by good evidence, try to falsify theories, etc.) With respect to the means-end side the rationality of science depends on whether scientific methods are efficient in achieving the aims of science Different accounts of the goals of science: truth, predictability, usability, etc. It must be possible to compare theories relative to the agreed goal(s). If there is sufficient evidence that T2 is goal-superior to T1 - and the scientific community perceives this - than they must abandon T1 in favour of T2 If the deontological rationality can be thought of as a duty to satisfy certain epistemic and non-epistemic ends, both conceptions can be combined: scientists have a duty to establish proper connections between their scientific theories and their scientific ends

Demarcating science and non-science Some formalists have claimed that scientific rationality is the only form of rationality that exists: To fail to be scientifc is to fail to be rational Other formalists go less far but are still quite skeptical towards beliefs that do not meet the(ir) standards of scientific rationality But how should science be demarcated from non-science? Positivists hold that the demarcation criterion is the same as the one that they believe separates meaningful from meaningless claims: the verification principle: an empirical statement has meaning iff it is empirically verifiable Next to meaningful empirical claims, positivists accept analytic claims. These are conceptual truths. They are true by virtue of their own meaning (e.g., 1+1=2) The verification principle is self-refuting though (why?) Popper s demarcation criterion is not meant to draw a line between claims that are meaningful and meaningless. He holds that non-scientific claims can still be meaningful. For Popper scientific claims are falsifiable

Expanding to Formal Evidentialism Formal Evidentialism is the model of rationality that results if we expand the formal approach to scientific rationality to all areas of human life Evidential principle ( beliefs need good inferential or non-inferential evidence ) o Proportionality principle ( believe with a firmness proportional to the evidence ) o Logicality principle ( rationality matter of practice-independent a priori analysis ) o Rule principle ( belief formation is a matter of following algorithmic rules ) o Foundationalism ( distinction between basic and non-basic beliefs ) o Formal evidentialists do not pay attention to the actual agents and the actual practices. There is no analysis of how people in different practices actually form and regulate their beliefs. Actual events are mere illustrations

The locus of rationality Formal evidentialists embrace the logicality thesis (rationality boils down to a logical system). So, the locus of rationality is ultimately in systems of propositions. Only (relations between) propositions can be (ir)rational Relations between inferential evidence and theories and relations between basic and non-basic propositions A rational belief is thus nothing more than a belief in a proposition that is rational(ly justified). And a rational person is nothing more than a person who believes only rational(ly justified) propositions It follows that for formal evidentialism rationality is not a relation between a particular kind of agent, in a particular kind of situation, and her beliefs. That s why concrete practices do not matter for formal evidentialists Formal evidentialists embrace person-independent idealized universal models Rationality is ultimately connected to propositions, not persons

External and internal rationality A distinction can be made between external and internal standards (criteria, conditions) for rationality Internal standards deal with how agents ought to govern their accepted beliefs. The focus is only on the beliefs present in an agent s belief system Principle of logical consistency External standards deal with the relation between an agent s belief system and the outside world. It is about what standards a belief must satisfy before it is allowed to enter or stay in an agent s belief system Evidential principle, Principle of proportionality or Principle of proper basicality

Internal standards for rationality The consistency principle Since any absurdity can be derived from a logical contradiction ( P and not-P ) it is often suggested as an internal standard that the collection of beliefs of the agent ( the agent sbelief system ) must be logically consistent An agent should not believe both All swans are white and There is a black swan The principle of deductive closure It is often suggested as an internal standard that the logical consequences of what is believed should be accepted by the agent as well If an agent believes All swans are white and the agent also believes John owns a swan , then the agent should also accept The swan that John owns is white

Revised version of both internal standards Many formalists acknowlegde that both standards are not feasible because it is impossible for people (having limited mental powers) to meet them People have many beliefs and aren t able to verify whether their whole belief system is consistent. Neither can they infer all consequences of their beliefs Moreover, it can be in fact argued for that our belief systems cannot be both reasonable and consistent (how?) Yet, both standards can be rephrased as ideals. For rationality it is not required to actually meet both ideals. It is sufficient to do the best we can to satisfy these ideals Revised principle of consistency People are rational only if they always try their best to bring it about that they eliminate as many inconsistencies as possible in what they believe o Revised principle of deductive closure People are rational only if they always try their best to bring it about that they accept as many consequences of what they believe o

A problem for deductive closure Consider Brigitte. She beliefs only propositions with a probability of being true of 80% or higher. Suppose that she believes All swans are white with probability 80% and John owns a swan with probability 80%. According to the principle of deductive closure she should accept as well The swan that John owns is white . But this cannot be right, since the likelihood of this proposition is (0.8)2 and therefore less than 80% The problem becomes even more pressing if we consider cases with many different propositions. Holding on to deductive closure would entail that we have to accept propositons that are in fact highly unlikely, which does not seem to be a rational thing to do To follow-up on this. Suppose that Brigitte has beliefs A, B, C and D with likelihoods 80%. Suppose that A, B and C together entail not-D. Is Brigitte s belief system contradictory? Is Brigitte forced to belief a contradiction if we take into account the principle of deductive closure? And if we take into account Brigitte s 80% rule as well?

Chapter 4: The Scientific and the Evidentialist Challenge to Religious Belief

The 20th century challenge to religious belief In the 20th century, much of the discussion about whether or not religious belief is rational or justifiable took formal evidentialism for granted It was not until the end of the 20th century that philosophers of religion started to realize that the issue of the rationality of religion is as much a question about the notion of rationality itself as its application to religion An early 20th century view of the rationality of religious belief was provided by positivism. Positivism can be characterized in the following way A statement is meaningful or has cognitive content if and only if it is analytic or empirically verifyable (the verification principle of meaning) o A meaningful statement is true if and only if it is logically proven (for analytical statements) or empirically verified (for empirical statements) o The above two principles constitute the scientific standard of rationality. Thus all meaningful (and thus all rational) beliefs must be scientific beliefs. Rationality is scientific rationality. To fail to be scientific is the same as to fail being rational o All non-scientific statements (religion, art, etc.) are nonsense, like Qg aW Dzz . So there are not even false. They are just meaningless empty of congitive content o

The verificationist challenge to religious belief 1. A statement has cognitive meaning if and only if it is analytic or empirically verifiable (the verification principle of meaning) 2. Religious statements are neither analytic nor empirically verifiable 3. Therefore, religious statements are cognitively meaningless So religious statements, such as God exists , are not even false. They say nothing false, because they say nothing at all. They are pseudo-statements We must distinguish between the semantical question of religious belief (are these beliefs meaningful?) and the epistemological question of religious belief (are these beliefs rationally acceptable?) Since according to the verification principle of meaning religious beliefs do not pass the semantic test, the second never arises. Religion is on this view thus strictly speaking not even irrational. It is a-rational

The falsificationist challenge to religious belief Philosophers of religion like Flew replaced the positivistic verification principle of meaning with a falsification principle of meaning A statement is cognitively meaningful if and only if it is analytic or empirically falsifiable (i.e, it is possible to say upfront in which situations it is falsified) o This principle leads to the falsificationist challenge to religious belief 1. A statement has cognitive meaning if and only if it is analytic or empirically falsifiable (the falsification principle of meaning) 2. Religious statements are neither analytic nor empirically falsifiable 3. Therefore, religious statements are cognitively meaningless

Responding to both challenges Many philosophers of religion who wanted to hold on to rationally justified religious beliefs, felt the need to somehow meet these challenges Typically they accepted the first premise of both challenges, and tried to argue that religious discourse is compatible with the verification or falsification principle. That is, they rejected the second premise But then some started to realize that both principles were themselves problematic. They are according to they own standards meaningless. Therefore, they are self-referentially incoherent (Plantinga) Moreover, it became clear that not even science is able to satisfy these demands. For many scientific theories it is not possible to specify the verification or falsification conditions The consensus became that both principles are inadequate. A statement does not have to adhere to these principles in order to be meaningful Religious beliefs passes the semantic test. But can they be rationally justified?

The scientific challenge to religious belief If religious beliefs are cognitively meaningful, the crucial question becomes whether they pass the epistemological test. Are these beliefs rational? Can they be rationally accepted? We may then consider the following scientific challenge to the rationality of religious belief 1. Religious beliefs must fulfill the same, or at least similar, standards of rationality as scientific beliefs in order to be considered rational 2. Religious beliefs do not fulfill the same, or at least similar, standards of rationality as scientific beliefs do 3. Therefore, religious beliefs are irrational Surely, to give this challenge content one must specifiy the standards of rationality science one thinks science satisfies

Responding to the scientific challenge Religious believers can respond to this challenge in three different ways The strong response Accept the first premise and reject the second by arguing that religion does in fact fulfill the same or similar rationality standards as science o The differentiation response Reject the first premise by arguing that religious beliefs are rational but meet (wholly) different standards of rationality as science o The irrationality response Accept the scientific challenge but claim that this does not count against religion, since religion has never meant to be rational o