Object-Oriented Programming in C++ with Dr. Ian Reid - Course Overview

Dive into the world of object-oriented programming with Dr. Ian Reid's course on C++. Learn about classes, methods, inheritance, polymorphism, and design patterns. Understand the principles of OOP and how to implement them using C++. Enhance your skills in data hiding, encapsulation, and templates. By the end of the course, you will master the basics of OOP and be able to write C++ programs with confidence.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

B16 Software Engineering Object Oriented Programming Dr Ian Reid 4 lectures, Hilary Term http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~ian/Teaching/B16

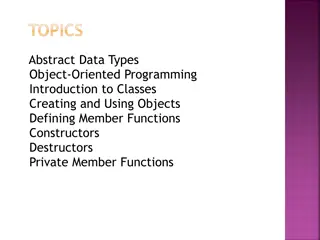

Object-oriented programming Introduction to C++ classes methods, function and operator overloading constructors, destructors program organisation Data hiding public and private data, accessor methods, encapsulation Inheritance Polymorphism Templates Standard Template Library; Design Patterns

Learning Outcomes The course will aim to give a good understanding of basic design methods in object-oriented programming, reinforcing principles with examples in C++. Specifically, by the end of the course students should: understand concepts of and advantages of object-oriented design including: Data hiding Inheritance and polymorphism Templates understand how specific object oriented constructs are implemented using C++ Be able to understand C++ programs Be able to write small C++

Texts Lipmann and Lajoie, C++ Primer, Addison-Wesley, 2005. Goodrich et al., Data structures and algorithms in C++, Wiley, 2004 Stroustrup, The C++ Programming Language, Addison-Wesley, 2000 Meyers, Effective C++, Addison- Wesley, 1998 Gamma et al., Design Patterns: elements of reusable object-oriented software, Addison-Wesley, 1995

Top down design Revisit ideas from Structured Programming Want to keep in mind the general principles Abstraction Modularity Architectural design: identifying the building blocks Abstract specification: describe the data/functions and their constraints Interfaces: define how the modules fit together Component design: recursively design each block

Procedural vs Object-oriented Object-oriented programming: Collaborating objects comprising code + data Object encapsulates related data and functions Object Interface defines how an object can be interacted with

Object Oriented Concepts Object/class Class encapsulates related data with the functions that act on the data. This is called a class. An object is an instance (a variable declared for use) of a class. Information hiding The ability to make object data available only on a need to know basis Interface Explicit separation of the description of how an object is used, from the implementation details Inheritance The ability to create class hierarchies, such that the inheriting class (super-class) is an instance of the ancestor class Polymorphism The ability of objects in the same class hierarchy to respond in tailored ways to the same events

Classes C++ predefines a set of atomic types bool, char, int, float, double C++ provides mechanism for building compound data structures; i.e. user-defined types class (c.f. struct in C) class generalises the notion of struct encapsulates related data and functions on that data C++ provides mechanisms so that user-defined types can behave just like the predefined types Matlab also supports classes

C++ classes A class (struct in C) is a user-defined data type which encapsulates related data into a single entity. It defines how a variable of this type will look (and behave) Class definition class Complex { public: double re, im; }; Don t confuse with creating an instance (i.e. declaring) int i; Complex z; Create a variable (an instance) of this type

Example: VTOL state Represent current state as, say, a triple of numbers and a bool, (position, velocity, mass, landed) Controller Single variable represents all numbers Better abstraction! state thrust Simulator class State { public: double pos, vel, mass; bool landed; }; state Display State s;

Accessing class members In Matlab introduce structure fields without declaration State s; s.pos = 1.0; s.vel = -20.0; s.mass = 1000.0; s.landed = false; s.pos = 1.0; s.vel = -20.0; s.pos = s.pos + s.vel*deltat; Thrust = ComputeThrust(s); Thrust = ComputeThrust(s);

Methods In C++ a class encapsulates related data and functions A class has both data fields and functions that operate on the data A class member function is called a method in the object-oriented programming literature

Example class Complex { public: double re, im; double Mag() { return sqrt(re*re + im*im); } double Phase() { return atan2(im, re); } }; Complex z; cout << Magnitude= << z.Mag() << endl; Call method using dot operator Notice that re and im do not need z. z is implicitly passed to the function via the this pointer

Information hiding / encapsulation Principle of encapsulation is that software components hide the internal details of their implementation In procedural programming, treat a function as a black box with a well-defined interface Need to avoid side-effects Use these functions as building blocks to create programs In object-oriented programming, a class defines a black box data structure, which has Public interface Private data Other software components in the program can only access class through well-defined interface, minimising side-effects

Data hiding example class Complex { public: double Re() { return re; } double Im() { return im; } double Mag() { return sqrt(re*re + im*im);} double Phase() { return atan2(im, re); } private: double re, im; }; Access to private members only through public interface Complex z; cout << Magnitude= << z.Mag() << endl; cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl; Read only access: accessor method

Data hiding example, ctd class Complex { public: double Re() { return r*cos(theta); } double Im() { return r*sin(theta); } double Mag() { return r;} double Phase() { return theta; } } private: double r, theta; Internal implentation now in polar coords }; Complex z; cout << Magnitude= << z.Mag() << endl; cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl; Unchanged!!

Constructor If we can no longer say z.re = 1.0; How can we get values into an object? Whenever a variable is created (declared), memory space is allocated for it It might be initialised int i; int i=10; int i(10); In general this is the work of a constructor

Constructor The constructor is a special function with the same name as the class and no return type Complex(double x, double y) { re = x; im = y; } or Complex(double x, double y) : re(x), im(y) {}

Data hiding example class Complex { public: Complex(double x, double y) { re = x; im = y; } double Re() { return re; } double Im() { return im; } double Mag() { return sqrt(re*re + im*im);} double Phase() { return atan2(im, re); } private: double re, im; }; Interface now includes constructor Complex z(10.0, 8.0); cout << Magnitude= << z.Mag() << endl; cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl; Declare (instantiate) an object of type Complex, setting its value to 10 + j 8

Data hiding example, ctd class Complex { public: Complex(double x, double y) { r = sqrt(x*x + y*y); theta = atan2(y,x); } double Re() { return r*cos(theta); } double Im() { return r*sin(theta); } double Mag() { return r;} double Phase() { return theta; } } private: double r, theta; Internal implentation now in polar coords }; Complex z(10.0,8.0); cout << Magnitude= << z.Mag() << endl; cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl; Unchanged!!

Copy Constructor The copy constructor is a particular constructor that takes as its single argument an instance of the class Typically it copies its data into the new instance The compiler creates one by default that does exactly this Not always what we want; need to take extra care when dealing with objects that contain dynamically allocated components Complex(Complex& z) { re = z.Re(); im = z.Im(); } Complex(Complex& z) : re(z.Re()), im(z.Im()) {}

Data hiding summary Cartesian Polar class Complex { public: Complex(double x, Complex(Complex& z) double Re() double Im() double Mag() double Phase() private: double r, theta; class Complex { public: Complex(double x, Complex(Complex& z) double Re() double Im() double Mag() double Phase() private: double re, im; double y) double y) }; }; Interface to the program remains unchanged Complex z(10.0,8.0); cout << Magnitude= << z.Mag() << endl; cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl;

C++ program organisation Complex.h class Complex { public: Complex(double x, double y); double Re(); double Im(); double Mag(); double Phase(); private: }; double re, im;

C++ program organisation Complex.cpp Scoping operator :: makes it explicit that we are referring to methods of the Complex class #include Complex.h Complex::Complex(double x, double y) { re = x; im = y; } double Complex::Re() { return re; } double Complex::Im() { return im; } double Complex::Mag() { return sqrt(re*re+im*im); } double Complex::Phase() { return atan2(im,re); }

const An object (variable) can be declared as const meaning the compiler will complain if its value is ever changed const int i(44); i = i+1; /// compile time error! It is good practice to declare constants explicitly It is good practice to declare formal parameters const if the function does not change them int foo(BigClass& x); versus int foo(const BigClass& x);

const Why mention this now? In C++ const plays an important part in defining the class interface Class member functions can (sometimes must) be declared as const Means they do not change the value of the calling object Enforced by compiler Notice that as far as code in a class member function is concerned, data fields are a bit like global variables They can be changed in ways that are not reflected by the function prototype Use of const can control this somewhat

const class Complex { public: Complex(double x, double y) { re = x; im = y; } double Re() { return re; } double Im() { return im; } double Mag() { return sqrt(re*re + im*im);} double Phase() { return atan2(im, re); } private: double re, im; }; const Complex z(10.0, 8.0); cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl; This code will generate an error

const class Complex { public: Complex(double x, double y) { re = x; im = y; } double Re() const { return re; } double Im() const { return im; } double Mag() const { return sqrt(re*re + im*im);} double Phase() const { return atan2(im, re); } private: double re, im; }; const Complex z(10.0, 8.0); cout << Real part= << z.Re() << endl; This code should now compile

Function overloading C++ allows several functions to share the same name, but accept different argument types void foo(int x); void foo(int &x, int &y); void foo(double x, const Complex c); The function name and types of arguments yield a signature that tells the compiler if a given function call in the code is valid, and which version is being referred to

Function overloading We can define exp for the Complex class #include <cmath> Complex exp(const Complex z) { double r = exp(z.Re()); Complex zout(r*cos(z.Im()), r*sin(z.Im())); return zout; }

Methods versus functions When should we use a member function and when should we use a non-member function? exp(z) versus z.exp() Consider carefully how it will be used Does it modify the instance? Which presents the most natural interface? In this case I would go for exp(z)

Operators Arithmetic + - * / % Relational == != < > <= >= Boolean && || ! Assignment = I/O streaming << >>

Operator overloading Suppose we want to add two Complex variables together Could create a function: Complex Add(const Complex z1, const Complex z2) { Complex zout(z1.Re()+z2.Re(), z1.Im()+z2.Im()); return zout; } But it would it be much cleaner to write: Complex z3; z3 = z1+z2;

Operator overloading C++ exposes the definition of the infix notation a+b as a function (prefix notation) operator+(a,b) Since an operator is just a function, we can overload it Complex operator+(const Complex z1, Complex zout(z1.Re()+z2.Re(), z1.Im()+z2.Im()); return zout; } Hence we can write Complex z3; Z3 = z1+z2; const Complex z2) {

operator= z3=z1+z2 We have assumed that the assignment operator (operator=) exists for the Complex class. Define it like this: Complex& Complex::operator=(const Complex& z1) { re = z1.Re(); im = z1.Im(); return *this; }

operator= Defn of operator= is one of the few common uses for the this pointer. z2=z1 is shorthand for z2.operator=(z1) operator= must be a member function The left hand side (here z2) is implicitly passed in to the function Function returns a reference to a Complex. This is so we can write z3=z2=z1; z3.operator=(z2.operator=(z1));

Operator overloading class SafeFloatArray { public: float& operator[](int i) { if ( i<0 || i>=10 ) { cerr << Oops! << endl; exit(1); } return a[i]; } C++ does no array bounds checking (seg fault) Create our own safe array class by overloading the array index operator [] }; private: float a[10];

Complete example Putting it all together: program to calculate frequency response of transfer function H(jw) = 1/(1+jw) Three files, two modules Complex.h and Complex.cpp Filter.cpp The first two files define the Complex interface (.h) and the method implementations Compile source to object files % g++ -c Filter.cpp % g++ -o Filter Complex.o Filter.o -lm % g++ -c Complex.cpp Link object files together with maths library (-lm) to create executable

// Complex.h // Define Complex class and function prototypes // class Complex { public: Complex(const double x=0.0, const double y=0.0); double Re() const; double Im() const; double Mag() const; double Phase() const; Complex &operator=(const Complex z); private: double _re, _im; }; // Complex maths Complex operator+(const Complex z1, const Complex z2); Complex operator-(const Complex z1, const Complex z2); Complex operator*(const Complex z1, const double r); Complex operator*(const double r, const Complex z1); Complex operator*(const Complex z1, const Complex z2); Complex operator/(const Complex z1, const Complex z2);

#include <cmath> #include <iostream> #include "Complex.h" // First implement the member functions // Constructors Complex::Complex(const double x, const double y) : _re(x), _im(y) {} Complex::Complex(const Complex& z) : _re(z.Re()), _im(z.Im()) {} double Complex::Re() const { return _re; } double Complex::Im() const { return _im; } double Complex::Mag() const { return sqrt(_re*_re + _im*_im); } double Complex::Phase() const { return atan2(_im, _re); } // Assignment Complex& Complex::operator=(const Complex z) { _re = z.Re(); _im = z.Im(); return *this; } // Now implement the non-member arithmetic functions // Complex addition Complex operator+(const Complex z1, const Complex z2) { Complex zout(z1.Re()+z2.Re(), z1.Im()+z2.Im()); return zout; }

// Complex subtraction Complex operator-(const Complex z1, const Complex z2) { Complex zout(z1.Re()-z2.Re(), z1.Im()-z2.Im()); return zout; } // scalar multiplication of Complex Complex operator*(const Complex z1, const double r) { Complex zout(r*z1.Re(), r*z1.Im()); return zout; } Complex operator*(const double r, const Complex z1) { Complex zout(r*z1.Re(), r*z1.Im()); return zout; } // Complex multiplication Complex operator*(const Complex z1, const Complex z2) { Complex zout(z1.Re()*z2.Re() - z1.Im()*z2.Im(), z1.Re()*z2.Im() + z1.Im()*z2.Re()); return zout; }

// Complex division Complex operator/(const Complex z1, const Complex z2) { double denom(z2.Mag()*z2.Mag()); Complex zout((z1.Re()*z2.Re() + z1.Im()*z2.Im())/denom, (z1.Re()*z2.Im() - z1.Im()*z2.Re())/denom); return zout; } // end of file Complex.cpp

#include <iostream> #include "Complex.h" using namespace std; Complex H(double w) { const Complex numerator(1.0); const Complex denominator(1.0, 0.1*w); Complex z(numerator/denominator); return z; } int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { double w=0.0; const double stepsize=0.01; Complex z; for (double w=0.0; w<100.0; w+=stepsize) { z = H(w); cout << w << " " << z.Mag() << " " << z.Phase() << endl; } }

Object-oriented programming An object in a programming context is an instance of a class Object-oriented programming concerns itself primarily with the design of classes and the interfaces between these classes The design stage breaks the problem down into classes and their interfaces OOP also includes two important ideas concerned with hierarchies of objects Inheritance polymorphism

Inheritance Hierarchical relationships often arise between classes Object-oriented design supports this through inheritance An derived class is one that has the functionality of its parent class but with some extra data or methods In C++ class A : public B { }; Inheritance encodes an is a relationship

Example class Window Data: width, height posx, posy Methods: raise(), hide() select(), iconify() class GraphicsWindow class TextWindow Data: background_colour Methods: redraw(), clear() fill() Data: cursor_x, cursor_y Methods: redraw(), clear() backspace(), delete() class InteractiveGraphicsWindow Data: Methods: MouseClick(), MouseDrag()

Inheritance Inheritance is an is a relationship Every instance of a derived class is also an instance of the parent class Example: class Vehicle; class Car : public Vehicle { }; Every instance of a Car is also an instance of a Vehicle A Car object has all the properties of a Vehicle Don t confuse this with a contains or composition relationship. class Vehicle { Wheels w[]; };

Polymorphism Polymorphism, Greek for many forms One of the most powerful object-oriented concepts Ability to hide alternative implementations behind a common interface Ability of objects of different types to respond in different ways to a similar event Example TextWindow and GraphicsWindow, redraw()

Implementation In C++ run-time polymorphism invoked by the programmer via virtual functions class Window { virtual void redraw(); };

Example Consider simple hierarchy as shown A is base class class A B and C both derive from A class B class C Every instance of a B object is also an A object Every instance of a C object is also an A object