Exploring the Role of Imagination in Healthcare Ethics

This discussion delves into the importance of incorporating imagination in healthcare ethics alongside rational approaches. It explores how imagination, as the mind's power to consider unreal or absent things, can enhance ethical thinking and response. The session covers diverse viewpoints on moral imagination, its relation to perception and belief, and its implications for healthcare ethics. Insightful examples and a critical analysis of different ethical approaches, including principle-based, utilitarian, and care-based ethics, are highlighted.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

MORAL IMAGINATION IN HEALTHCARE By Steven Farrelly-Jackson, PhD Associate Professor of Philosophy and Global Health Allegheny College University of Pittsburgh Consortium Ethics Program

Agenda Introduction: Preliminary thoughts. Imagination. Moral Imagination. Moral imagination in healthcare. Strengthening the moral imagination through engaging the humanities. Questions & discussion.

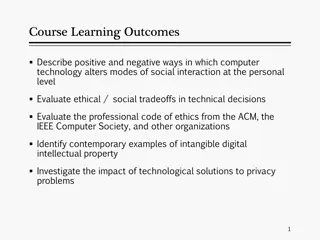

Preliminary Thoughts Three significant approaches to healthcare ethics: 1. Principle-based: ethical obligations stem from general rules/principles applied to particular cases. (Cf. AMA Code of Medical Ethics; the core principles of Bioethics .) Emphasis on reason and rational analysis. 2. Utilitarian: the right thing to do is the action calculated to produce the greatest benefit for the greatest number. Emphasis on reason and rational calculation of benefits and harms for all people affected. 3. Care-based: ethical obligations stem from particular relationships between care providers and patients. Emphasis on interpersonal connectedness through more humanistic qualities of understanding, responsiveness, trust and empathy.

Main Question Most theorizing in medical ethics has focused on rational approaches to moral problems in healthcare. Recently, greater acknowledgment of the importance of more affective dimensions to moral situations (e.g. involving sympathy, empathy, compassion). But what of the role of imagination in ethics? Arguably, engagement of the imagination is fundamental in all areas of ethical thinking and response. Aim of this discussion is to explore this.

Imagination Imagination = the power of the mind to consider things which are not present to the senses, and to consider that which is not taken to be real. Contrast with perception and belief. Two commonly-held ideas about imagination: (1) it involves the capacity to experience mental images (i.e. to consider things mentally in ways that are in some way related to sensory experience); (2) it involves the capacity to engage in creative thought (i.e. to form thoughts or images of things/possible worlds which are known not to be real).

Imagination and the World Asserted claims about the world true/false. In imagining X we do not normally assert X, so ideas of truth/falsity not normally invoked. However, imaginings about possible states of the world may be appropriate/plausible (or not) in respect of what we believe about actual world. Thus, a certain normativity to what/how we imagine, which implies that imagination not simply subjective or non-rational.

Examples of Imagination Conjecturing a hypothesis in science. Imagining how the present world could be different (= imagining a possible world ). Imagining what would happen in the future if some particular action were done, or not done, now (or what would have happened in the past if something else in the more distant past had or had not happened). Imagining what someone else is thinking/feeling. Imagining someone else s perspective on the world.

Examples of Imagination Imagining what it is like to be < > [sick, disabled, in pain ] Imagining how one would behave or feel in some hypothetical situation. Imagining oneself as different in some way. Creating an imaginary world in response to reading a novel; seeing three-dimensional objects in two-dimensional patches of paint; hearing melodies in sequences of sounds, and so on. Creating imaginary worlds through one s own words/painting/and so on.

Moral Imagination Imagination = that which enables us, by a voluntary effort, to conceived the absent as if it were present, the imaginary as if it were real, and to clothe it in the feelings which, if it were indeed real, it would bring along with it. This is the power by which one human being enters into the mind and circumstances of another. - John Stuart Mill, Bentham. (My emphasis.)

Moral Imagination Moral imagination = putting the imagination to use for moral purposes. Examples: Envisaging what the good life is (which we as individuals or a society should aim at attaining), or what an ideal, just society would be. Determining what sorts of moral principles we should develop to attain/maintain such a just society. (Cf. Kant, Rawls) Applying moral concepts to new situations we encountere. (Cf. the deepening or growth of our moral concepts.) Attempting to understand others experiences, needs, values and moral perspectives. ( Putting oneself in others shoes. ) Moral self-reflection. Enabling one to feel moral emotions such as sympathy, empathy, compassion for others plights. Enabling one to appreciate, and respond to, the internal dimension of others necessary for awareness of the separate reality of other persons.

Putting Oneself in Anothers Shoes. The attempt to enter imaginatively into the mind and circumstances of another is central to moral thinking: 1. The requirement to take the preferences, values, needs of others into account in order to attain proper understanding of an action/situation before making a particular moral judgment about it and/or deciding what should be done. 2. The requirement to understand and acknowledge another s needs, fears, experiences of pain and suffering in order to offer appropriate care, mobilize appropriate moral emotions, and so on.

Moral Understanding Before applying general moral principles, or calculating benefits/harms, essential to come to a clear and refined understanding of the particular moral situation at hand, and judge its most morally salient features. Such understanding, if it is to be truly moral, must take into account how others view the situation, what their values, needs, and preferences are, and in a deeper sense the respective meanings of this situation for their lives. For this, active engagement of the imagination is necessary.

Difficulties of Attaining Understanding General difficulties : 1. Complexity of real-world situations. 2. Attaining understanding of other minds. 3. Limited perspective of the individual moral thinker. 4. The gravitational force of individual subjectivity.

Imagination and Moral Emotions Question: do I need to imagine that someone with a visibly bad injury is in pain, or do I see that he/she is in pain? (Cf. Wittgenstein: The human body is the best picture of the human soul. ) But some imaginative effort to enter into the mind and circumstances of another is necessary to mobilize the full range of our affective responses if only because imagination often needed to reaffirm the separate reality, humanity and vulnerability of the other. The quality of responsiveness to someone conditions the nature of the relationship developed, and thereby the quality of communication (at every level) attained.

Responding to the Reality of Others Because your suffering makes a claim upon me. It is not enough that I know [in the sense of being certain] that you suffer, I must do or reveal something In a word, I must acknowledge it, otherwise I do not know what (your or his) being in pain means. Is. A failure to know might just mean a piece of ignorance, an absence of something, a blank. A failure to acknowledge is the presence of something, a confusion, an indifference, a callousness, an exhaustion, a coldness. Spiritual emptiness is not a blank. - Stanley Cavell To what extent is imagination needed for the sort of acknowledgment about which Cavell speaks? Charon: I had to acknowledge the reality of her life

Metaphor and Imagination Consider the idea that much of our thinking with concepts, values, principles, is metaphoric in nature using images, social imaginaries, narratives. (Cf. Rommetveit et al.) Metaphoric thinking necessarily uses the imagination. Importance of metaphor in ethical contexts: 1. Moral understanding and judgment: cf. applications of moral concepts like courage and cruelty. 2. Moral self-reflection. 3. Moral deliberation.

Limits to the Imagination If one has to imagine someone else s pain on the model of one s own, this is none too easy a thing to do: for I have to imagine pain which I do not feel on the model of pain which I do feel. That is, what I have to do is not simply make a transition in imagination from one place of pain to another. As, from pain in the hand to pain in the arm. For I am not to imagine that I feel pain in some region of his body. (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, 302) So I can imagine myself feeling pain in another body; I can try to imagine what it is like for someone else to feel pain (say toothache); but I cannot easily (or ever?) imagine the other s pain.

Limits to the Imagination More generally, I can imaginatively occupy another set of shoes (imagine myself in situation X); I can attempt to imagine what it would be like for another to be in X (taking the other s perspective in virtue of assumed commonly shared reactions/values); but I cannot imagine being that other person in X: I cannot inhabit that person s subjective view on the world. One reason for this limit on the imagination: imagination and embodiment. (Cf. Mackenzie & Scully) Can an able-bodied person really imagine what it is like to be significantly disabled?

Moral Imagination and Healthcare Recall the earlier distinction between principle-based, utilitarian and care-based approaches to ethical issues arising in healthcare: 1. Principle-based: ethical obligations stem from general rules/principles applied to particular cases. (Cf. AMA Code of Medical Ethics; the core principles of Bioethics .) Emphasis on reason and rational analysis. 2. Utilitarian: the right thing to do is the action calculated to produce the greatest benefit for the greatest number. Emphasis on reason and rational calculation of benefits and harms for all people affected. 3. Care-based: ethical obligations stem from particular relationships between care providers and patients. Emphasis on interpersonal connectedness through more humanistic qualities of understanding, responsiveness, trust and empathy. Moral imagination is necessary in all three approaches.

Applying Principles in Clinical Settings Some examples of challenges: The Principles of Beneficence/Non-maleficence. How do we determine best interests and harm for a particular patient? The Principle of Respect for Autonomy. How do we determine competence/incompetence in the case of a particular patient? Principles governing treatment/non-treatment decisions. How do we determine quality of life for incompetent adults at end of life, or project QOL for impaired infants? Principles governing surrogate decision-making. How does/can a person make a substituted judgment for someone else?

Example: Quality of Life Cf. AMA Code, Section 2.17: In the making of decisions for the treatment of seriously disabled newborns or of other persons who are severely disabled by injury or illness, the primary consideration should be what is best for the individual patient Quality of life, as defined by the patient s interests and values, is a factor to be considered in determining what is best for the individual. It is permissible to consider quality of life when deciding about life-sustaining treatment

Impaired Infants Cf. AMA Code, Section 2.215: The primary consideration for decisions regarding life-sustaining treatment for seriously ill newborns should be what is best for the newborn. Care must be taken to evaluate the newborn s expected quality of life from the child s perspective.

Questions Discussions about quality of life are common in ethics committee meetings, often in the context of debating whether treatment would be medically indicated or futile. What specific challenges do such ideas present? How can a general principle such as the AMA one quoted above be engaged with a particular case? What specific challenges arise for determining expected QOL for a severely disabled newborn? What is the role of the moral imagination here?

Medical Futility Cf. AMA Code, Section 2.037: When further intervention to prolong the life of a patient becomes futile, physicians have an obligation to shift the intent of care towards comfort and closure. However, there are necessary value judgments involved in coming to the assessment of futility

Defining Futility Complex controversial concept. Introduced in contexts where the medical capacity to sustain life does not enable the disease process to be reversed or for any desired state of functionality to be restored. Treatment serves only to prolong the process of dying in such a way that burdens are seen to outweigh benefits. Such treatments are said to be futile.

Questions about Futility Quantitative conceptions of futility. Based on statistical evidence as to the clinical efficacy of a given treatment in physiological terms. Some threshold figure demarcates the worthwhile effort to treat from the futile. Problem: different people (patients and physicians) will have different attitudes, and ascribe different values, to the same figures. Qualitative conceptions of futility. Futility can only be understood relative to certain specified goals. These goals express subjective values. Related to conceptions of perceived quality of life. Imagination needed for assessing quality of life, determining burdens and benefits for the patient, determining the meaning of continued life for that person.

PA Act 169: Definition of Incompetent Incompetent. A condition in which an individual, despite being provided appropriate medical information, communication supports and technical assistance, is documented by a health care provider to be: (1) unable to understand the potential material benefits, risks and alternatives involved in a specific proposed health care decision; (2) unable to make that health care decision on his own behalf; or (3) unable to communicate that health care decision to any other person. The term is intended to permit individuals to be found incompetent to make some health care decisions, but competent to make others.

Example: Competence/Incompetence General problem of autonomy: idealization. Few are ever ideally autonomous; arguably any seriously ill person will fall even further short of this ideal. Pain, medication, fatigue may all have an impact on autonomy. Individuals may vary in how well they can deliberate or make decisions in the presence or absence of other individuals, or in different settings (e.g. home vs. hospital). Problems of determination: judgments of competence should be contextual, sensitive to individual difference, alert to potential stress imposed by what s at stake, and geared to respect for patient s own goals/values. What role is there for imagination here?

PA Act 169: Substituted Judgment (5) (i) In the absence of instruction, the health care agent shall make health care decisions that conform to the health care agent's assessment of the principal's preferences and values, including religious and moral beliefs.

Substituted Judgment: Questions How can anyone ever determine what someone else would want in a given situation at a given time? How do we assess the significance for individual subjects of benefits/burdens of treatment as experienced by them? Relates to questions of personal value and what constitutes quality and meaning of life for a specific individual. Role of imagination in determining what another would want ?

Care and Healthcare Relationships Care-based ethics focus on unique relationships between care-givers and care- receivers. Obligations for each party stem from the specific context of their unique relationship. Motivation for caring grounded in natural human sentiments such as sympathy, kindness, compassion. Caring sometimes associated with virtue.

Care Ethics and Healthcare Useful definition of care for health contexts: Care involves the meeting of needs of one person by another where face-to-face interaction between carer and cared-for is a crucial element of overall activity, and where the need is of such a nature that it cannot possibly be met by the person in need herself. (Bubeck, 1995, p. 129)

The Ethics of Care Four elements of caring (Tronto, 1993: 126-137): 1. Attentiveness: attentiveness to the needs of others (includes the disposition to become aware of when others are in need). 2. Responsibility: the responsibility to respond to another s need and to offer care. 3. Competence: the requirement that one develop the competence to give adequate care. 4. Responsiveness: responsiveness to the vulnerability of those being cared for; being alert to the possibility of abuse of the vulnerable.

The Integrity of Care According to Tronto all four of these elements must be integrated into an appropriate whole. Care as a practice involves more than simply good intentions. It requires a deep and thoughtful knowledge of the situation, and of all the actors situations, needs and competencies. Those who engage in a care process must make judgments: judgments about needs, conflicting needs, strategies for achieving ends, the responsiveness of care-receivers, and so forth. (1993: 136-137)

Care and the Moral Imagination The elements of attentiveness and responsiveness to the needs, emotions and experiences of others draw directly on the moral imagination. The mobilizing of moral emotions like compassion and sympathy is also dependent to an extent on the imagination. The fundamental response to the patient as person, rather than simply as locus of symptoms, is also enabled by the moral imagination. (Cf. Schmidt on his need be responded to as a person.)

Strengthening the Moral Imagination A moral task in itself. Reinforce the disposition to pay attention to, and care about, the lives of others. The humanistic importance of the arts throughout cultural history. A recent development in medical education: Medical Humanities.

The Humanism of Medical Humanities In great fiction, the dream engages us heart and soul; we not only respond to fictional problems as though they were real, we sympathize, think and judge. We act out, vicariously, the particular modes of action, particular attitudes, opinions, assertions and beliefs exactly as we learn from life. Thus the value of great fiction is not just that it broadens our knowledge of people and places, but also that it helps us to know what we believe, reinforces those qualities that are noblest in us, leads us to feel uneasy about our failures and limitations. (John Gardner, The Art of Fiction)

Humanism 2 [Art and literature] can perform a miracle: they can overcome man s detrimental peculiarity of learning only from personal experience so that the experience of other people passes him in vain. From man to man, as he completes his brief spell on earth, art transfers the whole weight of an unfamiliar, lifelong experience with all its burdens, its colors, its sap of life; it recreates in the flesh as unknown experience and allows us to possess it as our own the only substitute for an experience we ourselves have never lived through is art, literature. (Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech)

Medical Humanities Engagement with arts/humanities is important for healthcare because it : enables individual health providers to explore the human dimensions of their work. to understand the needs and concerns of their patients engages health care professionals with humanistic perspectives and insights that help them do their work better. deepens participants understanding of their work and enriches their relationships with patients and one another. participants increase not only their job satisfaction and cultural awareness but also their empathy for patients. gives healthcare workers the opportunity to see through another person s eyes allows caregivers and patients to connect with each other as people. (All quotes taken from web-sites of official state programs of Literature and Medicine: Humanities at the Heart of Healthcare (first developed in Maine)

How the Humanities Can Help Develop the Moral Imagination Thoughtful engagement with art/literature can provide: Exercise of, and improved capacity for, imagination. Clarification of imagination and vision. Through the use of imagination, one can exercise and refine moral emotions. New imagined ways of looking at the world, which can then become new ways of looking at the world. Imaginative development of conceptual knowledge. Enhanced understanding. ( Acknowledgment )

Imaginative Projection A key humanist value of literature is said to be its strengthening of our capacity for imagination, in particular the sympathetic imagination needed to enter another person s world and perspective, to live with other values, and other outlooks in the deepest sense, to experience the life of another. (Cf. Tolstoy) Shelley: The great secret of morals is love, or a going out of our nature and the identification of ourselves with the beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person, not our own. A man to be greatly good must imagine intensely and comprehensively. ( A Defense of Poetry, 1821)

Clarification Of Imaginative Vision Henry James: The effort to really to see and really to represent is no idle business in the face of the constant force that makes for muddlement. The great thing is indeed that the muddled state too is one of the very sharpest of the realities, that it also has color, form and character ( Preface to What Maisie Knew)

Art and Literature as a Space for Freeing the Imagination Art/literature valuable for the moral imagination because makes it possible to explore ideas, possibilities, emotions and values in a way in which we are free to play with them, without immediate real-world implications. A novel, just because it is not our life, places us in a moral position that is favorable for perception and it shows us what it would be like to take up that position in life. We find here love without possessiveness, attention without bias, involvement without panic. (Martha Nussbaum: Love s Knowledge)

Imagination and the Moral Emotions: Love and Sympathy The importance for ethics of other-directed emotions like love, sympathy, empathy and compassion has long been recognized as crucial for overcoming the force- field of subjectivity the self-centered rush of ordinary life (Iris Murdoch) and really seeing and acknowledging the reality of another. George Eliot: The greatest benefit we owe to the artist, whether painter, poet or novelist, is the extension of our sympathies a picture of human life such as a great artist can give, surprises even the trivial and the selfish into that attention which is apart from themselves, which can be called the raw material of moral sentiment.

The Moral Emotions and Imagination The development of moral emotions is crucial to the moral growth of an individual: the capacities for love of others, sympathy, compassion, remorse, guilt, shame. The primary way we develop such emotions is engagement with other people, but humanists believe that art and literature are also crucial resources. Why crucial? Because art/literature, working through the imagination, can mobilize emotions we rarely feel in humdrum daily life, or which we feel but lack the time or space to reflect on. Art affords a safe space to get in touch with and explore our darker emotions; it enables emotional engagement with situations or people we could not otherwise (or easily) encounter.

New Imaginative Visions . Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life . Life holds the mirror up to Art, and either reproduces some strange type imagined by painter or sculptor, or realizes in fact what has been dreamed in fiction. . Things are because we see them, and what we see, and how we see it, depends on the Arts that have influenced us. (Oscar Wilde: The Decay of Lying, 1891)

The Arts and Conceptual Knowledge Imaginatively and thoughtfully engaging with serious art and literature can deepen our understanding of complex humanist concepts. Semantic depth of concepts like beauty, courage, cruelty, war, love, parenthood, and so on. It is precisely because the arts takes us imaginatively into the muddlement and complexity of human life that they can unsettle entrenched assumptions and fixed ways of conceiving and judging situations, and in so doing challenge us to re-examine the concepts that frame our responses to the world.

Acknowledgment and Literary Humanism When literary works are successful dramatic achievements, it is always in part because they fashion a sense of what is at stake in the specific regions of human circumstance they represent. literary works represent ways of acknowledging the world rather than knowing it. (John Gibson, Literature and Knowledge. ) For example, death is a concept we encounter daily in the context of other people; in The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Tolstoy takes us into the interior of another s life such that, imaginatively, we experience his confrontation with his own impending death, and all that that signifies for the life he has led as well as for what life remains to him. We know that life ends in death; Tolstoy s story portrays one way of acknowledging this.

Imagined Worlds and the Real World All the morally strengthening imaginative capacities that art and literature may enhance are capacities someone can have in the absence of a proper moral outlook, one which motivates us to care for others and aim to do what one believes to be morally right. There is a crucial gap between the humanistic imaginative experience we may have when watching a film or reading a novel and our actually doing anything in the world or changing anything about ourselves as a result. History supports Richard Posner s comment: Cultured people are not on the whole morally superior to philistines. Recall also the danger of illusory imaginative identification.

Crossing the Gap The gap between the arts and life can be crossed only by distinct activities on the part of the audience, both during the aesthetic experience and in the after-life of that experience. What sorts of activities? There are several intersecting activities all very familiar, but all very difficult: