Diving into Time in Narrative

Delve into the intricacies of time in narrative through the lenses of Genette and Woolf. Explore the subtle interplay between story, plot, and narrating, unraveling how narrative discourse manipulates time. Reflect on the essence of ordinary minds and the dark realms of psychology as portrayed by Virginia Woolf. Engage with the pseudo-time of texts and the fluidity of temporality in spatial forms. Unravel the dichotomy between story and narrative, where events unfold, and discourse reshapes perceptions of time.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

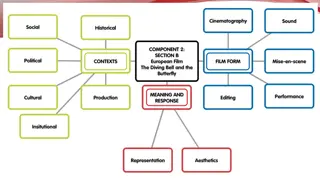

Time in Narrative Genette and Woolf

Reading portfolio: 6-8 pieces of writing engaging with a piece of writing, film, art in relation to concepts and theoretical ideas encountered on the module. Up to the appropriate total word length for your year. The theory can be applied in a more 'light touch' way than in an essay, as a jumping-off point for your own reflections. These can look like close readings (always good) but could be equally as good as a more discursive or broad-brush reflection on art, form, life, time.. But some engagement with form and with the specifics of a piece of writing or art in most of the pieces would be good. Up to two could be about your lived experience instead. Assessment (exmreplacement arrangements) Formative (for all): Assessments formative 1000-word reading of a piece of literature, film or visual art in relation to time by Friday of week 8, term 1 (27th November). Assessed: Intermediate Years: 100% assessed: 1 x 3000 word essay (40%); 1 x 3500 reading portfolio (60%) 50/50: 1 x 3000 word essay (40%); 1 x 3500 reading portfolio (60%) Assessed: Final Years: 100% assessed: 1 x 4000 word essay (40%); 1 x 4500 word reading portfolio(60%) 50/50: 1 x 4000 essay (40%); 1 x 4500 word reading portfolio(60%) Essay: Term 2, week 7 Reading portfolio: Term 3, week 2

Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad impressions trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come, an incessant shower of innumerable atoms; and as they fall, [ ] they shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday [ ]; so that, if a writer were a free man and not a slave [ ] if he could write what he chose, not what he must, if he could base his work upon his own feeling and not upon convention, there would be no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style [ ] Virginia Woolf, Modern Fiction (1919) For the moderns that , the point of interest, lies very likely in the dark places of psychology.

In his careful and subtle study of the relationships among story, plot, and narrating, Genette pays close attention to the functioning of the infinitely variable gearbox that links the told to the ways of its telling, and how the narrative discourse [ ] works to subvert, replay, or even pervert the normal passages of time. Peter Brooks, Reading for the Plot (1984), 20 [A book a spatial form ] metonymically borrows a temporality from the time of its reading: what [Genette] calls a pseudo-time of the text.

The story (what actually happened): The murder (1), the discovery of the murder/clues (2), the capture of the murderer (3) Story vs narrative/ discourse The narrative/discourse: The discovery of the murder (A), the uncovering of the circumstances of the murder (B), the capture of the murderer (C) Narrative = A2, B1, C3

Genettes coding: Sequence (A, B, C; then/once [1], now [2], new term?) Analepsis (internal or external), prolepsis, reach, extent Mrs Dalloway: 24 hrs: a woman s whole life in a single day Mrs Dalloway (1925) Passage of Mrs Dalloway Memory? Is the analepsis external or internal? So: Determining A, B, C (order events told to us) Determining what I m calling 1, 2, 3 (order things really happened ) Determining what is once/then [new symbol?], what now of the narrative (Clarissa s present, her day preparing for the party in London)

A, B, C (order in the story what really happened ) 1, 2, 3 (order in the narrative (the order the story, or bits of the story, are told)) Genette, order, coding past/then now

Have a go in your groups: Channel 1 MATTHEWS, GABRIELLE (UG) [excused absence] BATES, AIM E (UG) SCRIBE/ SPOKESPERSON FLOYD, OLIVIA (UG) CLARK, ISABELLA LYNDON-STANFORD, SOPHIA (UG Channel 2 SHARMA, KRISHNA (UG) SCRIBE/ SPOKESPERSON DHALIWAL, ESHA (UG) HULME-TEAGUE, SELWIN (UG) HILL, ELIZABETH (UG) [excused absence] MCMACKIN, CHARLI (UG) Channel 3 TAYLOR, EVIE (UG) SCRIBE/ SPOKESPERSON YANG, LONNIE (UG) AHMAD, MEHR (UG) ELGADDAL, NADIA (UG)

Mrs Dalloway, pp. 29-32 A Sally sitting on the floor B Clarissa seeing a man dropping dead in a field C Sally cutting heads off flowers A, B, C (order in the narrative) 1, 2, 3 (order in the story) past/then now D Sally running down the passage naked E feeling that Sally gives her [not a discrete event but almost the point of all this so we need to register it ] F NOW (can t get feeling back) G Clarissa at dressing table back in past and back at Bourton H Sally in gauze, at the fireplace I Clarissa meets Peter (intrudes upon her joy) J NOW lays her brooch down [lots of novel] K Sally appears in the present of the novel, at the new party

A Sally sitting on the floor (2) B Clarissa seeing a man dropping dead in a field (1) C Sally cutting heads off flowers (3) D Sally running down the passage naked (4) E feeling that Sally gives her [not a discrete event but almost the point of all this so we need to register it ] F NOW (can t get feeling back) (8) G Clarissa at dressing table back in past and back at Bourton (5) H Sally in gauze, at the fireplace (6) I Clarissa meets Peter (intrudes upon her joy) (7) J NOW lays her brooch down (9) [lots of novel] K NOW Sally appears in the present of the novel, at the new party (10) B1 A2 C3 D4 G5 F8 H6 I7 J9 .K10 EEEEEEEEEEEEE EEEE A, B, C (order in the narrative) 1, 2, 3 (order in the story) past/then now Highlight present of the novel

Most of the memories are external analepsis (because the novel spans only one day). What implications does this have for the mood and affective landscape of the novel? Its relationship to history? Does it make the past more significant sheer volume of words that refer to the past? Or is the fact that the memories refer to a time outside the time of the story make them less significant (less instrumental not plot points affecting the evolving story, or only very indirectly)? Prize to anyone who can find a prolepsis in Mrs Dalloway. Why are there none (properly speaking)? Can anyone explain? Analepsis In her diary entry of August 30th 1923 Woolf refers to her tunnelling process : How I dig out beautiful caves behind my characters: I think that gives exactly what I want; humanity, humour, depth. The idea is that the caves shall connect and each comes to daylight at the present moment (Woolf, L. 1982: 60)

How do the transitions between moments in time (and the tenses used) relate to the feelings produced? What do we learn about memory in these descriptions? (Does it ring true to you?) Clarissa, Sally, Bourton: Time, Memory and Desire [E.g. If Clarissa (or we) feels emotion in the present in thinking of the past, when (if ever) is it a repetition or a simulacrum of the emotion that was being felt in the past, and when something different?] How are time and space/place linked, if at all, in the passage (and elsewhere)? Is there any relation at all between the sexual content (the homosexuality, and/or the fact it is desire between women) and time? What relationship do these memories of Sally have with the rest of the novel?

Peter Brook, Reading for the Plot: Narrative the play of desire in time. (xiii) [In the text itself desire to order compels the plot s unfolding; the space between text and reader, wherein the reader s desire for plot impels the reading (see Brooks, 37-61)] Desire, time and narrative Desire is the motor of narrative Desire is also unarrestable, always desire for something else, since it is constituted in the split between need and demand, born from a lack, founded on fictional scenarios of fulfilment. (78)

Inaccessible, because unverifiable, relation of duration between narrative and story. Speed : the relationship between a duration (that of a story, measured in seconds, minutes, hours, days, months and years) and a length (that of a text, measured in lines and in pages. A narrative can do without anachronisms, but not without anisochronies, effects of rhythm. Four effects: ellipsis, descriptive pause, scene and summary Analysis of rhythm of Proust s A la Recherche (how much the pace how much time covered) speeds up and slows down (and jumps over periods of time). variations: from 150 pages for three hours, to three lines for twelve years internal evolution re. the narrative s end (slowing down of narrative very long scenes covering a short time in the story; but also ellipses). Think of examples of books you ve read which cover large or small time spans, or jump over great swathes of time, or otherwise do interesting things with such mechanisms Duration: Narrative Discourse, 87- 88

undefined

undefined

undefined

undefined