Understanding Company Attribution Rules in Legal Proceedings

Company attribution rules in legal proceedings are outlined, focusing on primary rules found in a company's constitution, general principles of agency, and exceptions where traditional attribution methods may not apply. The interpretation of laws involving companies and the application of specific attribution rules are discussed, emphasizing the importance of determining how acts and decisions are attributed to a company. Various categories of cases related to fraud and breach of directors' duty are examined, highlighting scenarios when claims may arise against directors, employees, or third parties. The significance of crafting special rules of attribution for specific substantive rules is also emphasized.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Attribution: Singularis EDMUND NOURSE Q.C. ONE ESSEX COURT

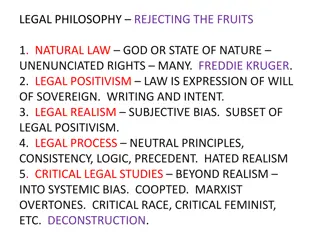

Meridian Global Funds Management Asia Ltd v Securities Commission [1995] 2 AC 500 (1) The company s primary rules of attribution will generally be found in its constitution, . and will say things such as the decisions of the board in managing the company s business shall be the decisions of the company. (2) general rules of attribution which are equally available to natural persons, namely, the principles of agency. It will appoint servants and agents whose acts, by a combination of the general principles of agency and the company s primary rules of attribution, count as the acts of the company (3) The company s primary rules of attribution together with the general principles of agency, vicarious liability and so forth are usually sufficient to enable one to determine its rights and obligations. In exceptional cases, however, they will not provide an answer. This will be the case when a rule of law, either expressly or by implication, excludes attribution on the basis of the general principles of agency or vicarious liability.

One possibility is that the court may come to the conclusion that the rule was not intended to apply to companies at all; for example, a law which created an offence for which the only penalty was community service. Another possibility is that the court might interpret the law as meaning that it could apply to a company only on the basis of its primary rules of attribution, i.e. if the act giving rise to liability was specifically authorised by a resolution of the board or an unanimous agreement of the shareholders. But there will be many cases in which neither of these solutions is satisfactory; in which the court considers that the law was intended to apply to companies and that, although it excludes ordinary vicarious liability, insistence on the primary rules of attribution would in practice defeat that intention. In such a case, the court must fashion a special rule of attribution for the particular substantive rule. This is always a matter of interpretation: given that it was intended to apply to a company, how was it intended to apply? Whose act (or knowledge, or state of mind) was for this purpose intended to count as the act etc. of the company? One finds the answer to this question by applying the usual canons of interpretation, taking into account the language of the rule (if it is a statute) and its content and policy.

CATEGORIES OF CASES RELATING TO FRAUD/BREACH OF DIRECTORS DUTY: BILTA at [87]. (1) When a third party is pursuing a claim against the company arising from the misconduct of a director, employee or agent. (Royal Brunei as regards Tan s company; El Ajou) (2) When the company is pursuing a claim against a director or an employee for breach of duty or breach of contract (or an accessory). (Belmont) (Accessories: Royal Brunei- as regards Tan; Bilta). (3) When the company is pursuing a claim against a third party not involved in the fraud for failing to prevent the fraud of the company s own agents, or for an indemnity against the fraud s consequences (Berg, Stone & Rolls, Singularis).

SINGULARIS ON THE ATTRIBUTION ISSUE 34. I agree [that Singularis was not a one person company]. But in any event, in my view, the judge was correct also to say that There is no principle of law that in any proceedings where the company is suing a third party for breach of a duty owed to it by that third party, the fraudulent conduct of a director is to be attributed to the company if it is a one-man company : [2017] Bus LR 1386, para 173. In her view, what emerged from Bilta was that the answer to any question whether to attribute the knowledge of the fraudulent director to the company is always to be found in consideration of the context and the purpose for which the attribution is relevant , para 182. I agree and, if that is the guiding principle, then Stone & Rolls can finally be laid to rest. 35. The context of this case is the breach by the company s investment bank and broker of its Quincecare duty of care towards the company. The purpose of that duty is to protect the company against just the sort of misappropriation of its funds as took place here. By definition, this is done by a trusted agent of the company who is authorised to withdraw its money from the account. To attribute the fraud of that person to the company would be, as the judge put it, to denude the duty of any value in cases where it is most needed : para 184. If the appellant s argument were to be accepted in a case such as this, there would in reality be no Quincecare duty of care or its breach would cease to have consequences. This would be a retrograde step.

36. Daiwa makes two further argumentsessentially policy argumentsagainst this conclusion. First, it argues that it is odd if the claim of a company arising out of the dishonest activities of its directing mind and will against a negligent auditor fails (as in Stone & Rolls [2009] AC 1391 and in Berg Sons & Co Ltd v Adams [1993] BCLC 1045 ) but a claim against a negligent bank or broker succeeds. But (quite apart from the difficulties of Stone & Rolls ) this ignores the fact that the duties of auditors are different from the duties of banks and brokers. The auditor s duty is to report on the company s accounts to those having a proprietary interest in the company or concerned with its management and control. If the company already knows the true position (as in Berg) then the auditor s negligence does not cause the loss. 37. Second, Daiwa argues that the law should not treat a company more favourably than an individual. In Luscombe v Roberts (1962) 106 SJ 373, a solicitor s claim against his negligent accountants failed because he knew that what he was doing transferring money from his clients account into his firm s account and using it for his own purposes was wrong. But companies are different from individuals. They have their own legal existence and personality separate from that of any of the individuals who own or run them. The shareholders own the company. They do not own its assets and a sole shareholder can steal from his own company. 38. I therefore see nothing in those arguments to detract from the conclusion reached that, for the purpose of the Quincecare duty of care, the fraud of Mr Al Sanea is not to be attributed to the company. However, even if it were, for the reasons given earlier, none of the defences advanced by Daiwa would succeed.

Key Cases (and other cases cited): Meridian Global Funds Management Asia Ltd v Securities Commission [1995] 2 AC 500 Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass [1972] AC 153 Tesco Stores Ltd v Brent London Borough Council [1993] 1 WLR 1037 Royal Brunei Airlines Sdn Bhd v Tan [1995] 2 AC 378 El Ajou v Dollar Land Holdings plc [1994] 2 All ER 685; [1994] 1 BCLC 464 Bilta (UK) Ltd (in liquidation) and others v Nazir and others (No 2) [2015] UKSC 23; [2016] AC 1 Belmont Finance Corpn Ltd v Williams Furniture Ltd [1979] Ch 250; [1979] 1 All ER 118 , CA Belmont Finance Corpn Ltd v Williams Furniture Ltd (No 2) [1980] 1 All ER 393 , CA Stone & Rolls Ltd v Moore Stephens [2009] UKHL 39; [2009] AC 1391 HL(E) Moulin Global Eyecare Trading Ltd v Inland Revenue Comr [2014] HKFCA 22; 17 HKCFAR 218; [2014] HKC 323 Berg Sons & Co Ltd v Mervyn Hampton Adams [1993] BCLC 1045; [2002] Lloyd s Rep PN 41 Singularis Holdings Ltd (in liquidation) v Daiwa Capital Markets Europe Ltd [2019] UKSC 50 [2019] 3 W.L.R. 997 Bowstead & Reynolds on Agency, 21st Ed: 1-028-29; 8-214-5.