Reflections on Nature and Society in English Literature

In the juxtaposition of "The Lonely Londoners" by Sam Selvon and "The Country and the City" by Raymond Williams lies a profound examination of historical context, societal dynamics, and the evolving relationships between text and culture. Stuart Hall's insights further enrich this reflective exploration, challenging conventional views on English rural life and literary heritage. The discourse delves into the transformative shifts in rural England, encapsulating the interconnectedness between human labor and nature. Ultimately, these works collectively resonate as a poignant ode to Britain's unique blend of tradition and change.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Sam Selvon, The Lonely Londoners (1956) & Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (1973)

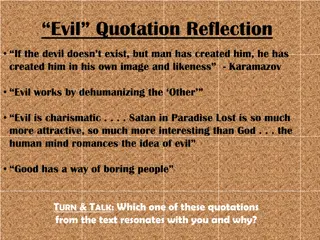

Stuart Hall: In The Country and The City, Raymond Williams brought to bear, against the well-entrenched, dominant conception of the English country house poetic tradition, a sense of historical context, and an understanding of the complex interplay between text and society, so powerful that it is simply not possible, ever again, to read it in the old way. [. . .] The poems and their cultural settings [. . .] are re-positioned in our imagination and understanding. The mystification of agrarianism , which still sustains the Heritage impulse in contemporary English cultural life, is slowly dissolved and becomes, in its suffocatingly philistine-civilised forms, untenable as a serious intellectual proposition.

Escalator effect: had not critics insisted that it was here, in Hardy, that we found the record of the great climacteric change in rural life: the disturbance and destruction of what one writer has called the timeless rhythm of agriculture and the seasons ? And that was also the period of Richard Jefferies, looking back from the 1870s to the old Hodge , and saying that there had been more change in rural England in the previous half-century that is, since the 1820s than in any previous time. [. . .] But now the escalator was moving without pause. For the 1820s and 1830s were the last years of Cobbett, directly in touch with the rural England of his time but looking back to the happier country, the old England of his boyhood, during the 1770s and 1780s. Thomas Bewick, in his Memoir, written during the 1820s, was recalling the happier village of his own boyhood, in the 1770s. The decisive change, both men argued, had happened during their lifetimes. John Clare, in 1809, was also looking back Oh, happy Eden of those golden years to what seems, on internal evidence, to be the 1790s, though he wrote also, in another retrospect on a vanishing rural order, of the far-fled pasture, long evanish d scene . Yet still the escalator moved .

Williams (in Ideas of Nature): We have mixed our labour with the earth, our forces with its forces too deeply to be able to draw back and separate either out

That is the best of Britain and it is part of our distinctive and unique contribution to Europe. Distinctive and unique as Britain will remain in Europe. Fifty years from now Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers and - as George Orwell said - old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist and if we get our way - Shakespeare still read even in school. Britain will survive unamendable in all essentials. John Major (PM, 1991-97), Speech to Conservative Group for Europe, 1993.

References to Englands heritage became a feature of the discourse of the government at this time, and the most blatant example can be seen in the Prime Minister s St George s Day speech in 1993. In his address to the nation, John Major deliberately used cricket to invoke a mythical, nostalgic and implicitly white notion of England , an essentially rural country full of invincible green suburbs , with Englishmen drinking warm beer to the distant sounds of cricket being played on the village green. [. . .] Major s speech represented an attempt to promote dreamlike constructions of earlier golden ages as a way of managing contemporary political, economic and social problems Nick Miller, in Cricket and National Identity in the Postcolonial Age, p. 235.

while this England did not exist in multicultural Britain, the continuing refuge in nostalgic discourse of Englishmen playing village cricket had clear racial connotations. The imagined version of Major s Britain is presented as a homogeneous community undivided by race and culture, one prior to the immigration of the many black and Asian people who came to settle in Britain from the colonies. The increasing presence of this alien culture is represented as the enemy within and invites the conclusion that national decline and weakness coincided with the arrival of black immigrants. Nick Miller, in Cricket and National Identity in the Postcolonial Age, p. 235.

The new rural economy of the tropical plantations sugar, coffee, cotton was built by this trade in flesh, and once again the profits fed back into the country-house system. Much of the real history of city and country, within England itself, is from an early date a history of the extension of a dominant model of capitalist development to include other regions of the world. And this was not, as it is now sometimes seen, a case of development here, failure to develop elsewhere. What was happening in the city , the metropolitan economy, determined and was determined by what was made to happen in the country ; first the local hinterland and then the vast regions beyond it, in other people s lands Thus one of the last models of city and country is the system we now know as imperialism. (Raymond Williams, The Country and the City, pp. 334-5)

Dwelling Places in Selvons fiction: Sam Selvon s fiction is largely organized around basement and bedsit life (James Procter, Dwelling Places, p. 31. Housing is an exclusionary environment in The Lonely Londoners, imposing an architecture of segregation and individuation. [. . .] These little worlds contain and separate families and cultures, keeping at a distance the different ethnic communities of the city. At the same time, Selvon s basement fictions repeatedly disrupt the public/private thresholds installed by the English dwelling place. The basement described here is also church , a site of congregation and public exchange. Moreover, the majority of tales and anecdotes that comprise The Lonely Londoners unfold indoors. The basement in this context becomes an important repository for a group consciousness. (Ibid., p. 46) Tanty s settlement in London is founded on a village-based existence exported from the Caribbean and is part of a more sustained communal establishment of location within The Lonely Londoners. [. . .] These emergent sites of accommodation appear as pockets or clusters at which the narrative tends to dwell within a predominantly white environment. As the text gravitates towards these dwelling places, alternative maps of the city emerge. Such localized or regional centres of West Indian settlement provide vernacular havens, which, whle being inescapably metropolitan, also clearly transplant the values, practices and geographies of a culture left behind. (Ibid., p. 58)

Williams: the great buildings of civilization; the meeting- places; the libraries and theatres, the towers and domes; and often more moving than these, the houses, the streets, the press and excitement of so many people, with so many purposes. I have stood in many cities and felt this pulse: in the physical differences of Stockholm and Florence, Paris and Milan: this identifiable and moving quality: the centre, the activity, the light. Like everyone else I have felt also the chaos of the metro and the traffic jam; the monotony of the ranks of houses; the aching press of strange crowds. But this is not an experience at all, not an adult experience, until it has come to include also the dynamic movement, in these centres of settled and often magnificent achievement.

Williams, Notes on English Prose 1780-1950: The scale and nature of the change break through the composed forms and set out in new ways. [. . .] We can then see more clearly what Dickens is doing: altering, transforming a whole way of writing, rather than putting an old style at a new experience. It is not the method of the more formal novelists, including the sounds of measured or occasional speech in a solid frame of analysis and settled exposition. Rather, it is a speaking, persuading, directing voice, of a new kind, which has taken over the narrative, the exposition, the analysis, in a single operation. Here, there, everywhere: the restless production of a seemingly chaotic detail; the hurrying, pressing, miscellaneous clauses, with here a gap to push through, there a restless pushing at repeated obstacles, everywhere a crowding of objects, forcing attention; the prose, in fact, of a new order of experience; the prose of the city. It is not only disturbance; it is also a new kind of settlement (93-4).

Selvon: where all these women coming from you never know but every year the ranks augmented with fresh blood from the country districts who come to see big life in London and the bright lights (107)

Structure of feeling: The term is difficult, but 'feeling' is chosen to emphasize a distinction from more formal concepts of 'world-view' or 'ideology'. It is not only that we must go beyond formally held and systematic beliefs, though of course we have always to include them. It is that we are concerned with meanings and values as they are actively lived and felt, and the relations between these and formal or systematic beliefs are in practice variable [. . .]. We are talking about characteristic elements of impulse, restraint, and tone; specifically affective elements of consciousness and relationships: not feeling against thought, but thought as felt and feeling as thought: practical consciousness of a present kind, in a living and interrelating continuity. (Marxism and Literature, 132)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjlS66XJ1Bs&list=PLIpn89AXGQEHz6bC 2OvjNovG4tjKMlEms