The European Renaissance: An Intellectual Movement Towards a New Society

The European Renaissance blossomed in Italy in the 15th century, marking a transition from feudalism to a bourgeois society. It emphasized courage, exploration, and a secular view of life, shaping a new image of man. Inspired by Greek thinking, it valued human achievements and rationality over mysticism. Machiavelli's methodology was grounded in practical human experiences rather than philosophical or religious ideals.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

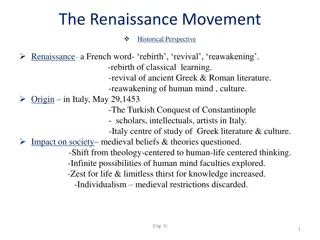

The Context Renaissance, the intellectual movement, first bloomed in Italy where through out the 15thcentury its finest fruits were manifest in diverse branches of creative thinking. It soon spread to almost every country of Western Europe, though varying in its content from country to country. European renaissance was actually necessitated by the changing social forces leading to the decline of the feudal order and the emergence of the bourgeoisie- a new class trying for its dominance in European society.

Renaissance: A Bourgeois Ethos The renaissance was essentially a bourgeois ethos- a kind of intellectual climate best suited to the needs of a completely new mode of economic operations on the basis of which a new society was about to evolve in Europe. The economic revolution thus brought about required for its survival and success a new set of conditions and a new set of values. The development of commerce and industry naturally called for continuous exploration and expansion and this meant a total break with the erstwhile attitude of life- A timid submission to the static order of feudal society was now replaced by a courageous defiance of all natural and artificial barriers.

Need for a New Image of Man The rising bourgeoisie, to assert their authority and safeguard their economic progress, needed a new image of man- a man brave and self-confident. A man who would make his own laws on the anvil of a secular view of life and confidently direct these laws to his final goal of material success. The Renaissance was, in essence, man s awakening about himself- about his autonomous sphere of authority and about his colossal power and possibilities. The renaissance naturally preached a secular and scientific view of life to brighten this image of man. Nothing was any longer treated as final and unquestionable.

Inspiration from Greek Thinking The spirit of adventure and enquiry was more sharpened by its inspiration from Greek thinking where human life was sought to be interpreted clearly in a mundane context, where earthly achievements were more treated as an outcome of human will and personality and where most of the things of life were settled not on the basis of a mystic faith but on the basis of a labourious process of reasoning. Truly embodying the aggressive spirit of bourgeois economic ventures, the renaissance made material success the prime goal of life and refused to make any compromise with the rigid moral rules that might inhabit the pace of this success. Renaissance did not totally discard moral and religious prescriptions. However, it took them as irrelevant and unnecessary in so far as man s struggle for life was concerned.

Machiavellis Methodology Machiavelli derives nothing a priori. His assumptions are built up neither with the aid of a philosophical transcedentalism nor on the basis of a so-called religious fetishism. They, rather, result from hard human facts from historical lessons and from his own personal experiences. His data drawn from man as he has been or he is and not from man as he ought to be. Machiavelli, certainly, is a political analyst and not a political philosopher. He treats politics not philosophically but empirically. His empirical observations produce a highly disagreeable picture of man- an ungrateful and selfish creature who cares only for his power and fame, his success and security. Machiavelli develops a thoroughly secular view of human virtue without being tied to morality and traditional norms.

Success, Power and Fame: Chief End in Man s Life Achieving success, power and fame happens to be the chief end in the life of man. Man s virtue, Machiavelli believes, is nothing but those qualities which facilitate the attainment of this goal. Thus to him good is what is a good means for reaching the mundane goals of material greatness and power. Machiavelli s man is, further, a master of his own fate. He would not meekly submit to fortune , taking it to be an irresistible force. Fortune, to Machiavelli, is like a woman who has to be kept under control only by a rough handling. This is why Machiavelli has so much contempt for the traditional Christian values such as humility, submissiveness, resignation and asceticism.

Glorifies Mans Cruel Aggressiveness According to Machiavelli, success alone is the criterion of man s greatness whatever the means he employs for achieving it. Human life, to him, is a continuous battle which has to be won at any cost. Those who win it are alone good and honourable and they only have the right to rule over others. The man he depicted was nothing but the bourgeois man that was just appropriate for speeding up the process of dynamic economic activities already underway in European society. The new economic order, for its success, no doubt, called for cruelty, selfishness and aggression as the desired qualities on the part of those who controlled this order. Machiavelli was putting a theoretical armour around this new economic order and around the new class who required an ideational defence of their practice.

The Historical Perspective of Machiavelli s Ideas To blame Machiavelli on a personal note for producing a wicked doctrine would be an act of gross oversimplification as that would amount to ignoring the correct historical perspective of his ideas. Thus the savageries manifest in his ideas are not alone his personal product; they are more the reflection of the cruelties of the class Machiavelli stood for. And this is why it is necessary to study Machiavelli taking him to be a child of the European Renaissance- the unique intellectual movement serving the growing needs of Europe s emerging bourgeoisie. But the bourgeois development in Italy had its own peculiarities. These local conditions in Italy are highly relevant to understand Machiavelli since they very much conditioned the theme of such ideas.

The Historical(contd.) European trade and commerce led to a fundamental social change in Europe first flourished in Italy. Italy had a geographical condition ideal for commercial activities and thus she became an important gateway of European trade with the East as early as in 10th century. The Italian Renaissance emerged to represent the spirit of the increasing bourgeoisation of Italian society. In 15thcentury that witnessed the political unification of a number of important European countries Italy was in the midst of dismal political condition. It was still a country fragmented into too many city states; there was utter lack of national unity. Italy was far from being a nation state.

Excessive Competition and Rivalry among the Bourgeoisie This strange political condition was mainly due to an excessive competition and rivalry among the Italian bourgeoisie themselves. Although Italian trade and industry had greatly expanded there was hardly any internal market for them in Italy. So with a lot of dependence on foreign buyers the different Italian city states intensely vied with each other for having a monopoly over the foreign market. Thus, by the end of 15thcentury, there were in Italy, besides the city of Rome, four other important city states- Milan, Venice, Florence and Naples- each an independent republic.

Political Instability Their jealousy and contempt for each other severely affected their political strength and made them frequent victims of the political aggrandisement of France, Spain and Germany. The entire political atmosphere was uncertain and insecure. Despite spectacular economic changes the corresponding political changes toward a stable and unified order were persistently eluding Italy. Although, culturally, the Italian Renaissance was in the fullest bloom, politically, it made little advance. Machiavelli was writing his doctrine at this confluence of the success and failure of the Italian Renaissance. The political disunity of Italy causing much of her political weakness was his major concern.

Political(contd.) In the closing chapter of his Prince, not in keeping with the dispassionate detachment that characterized all his political writings, he made a highly emotional appeal for bringing Italy s political unification. Machiavelli tried to grow a political atmosphere congenial to the bourgeois social development in his country and thereby sought to take the Italian Renaissance to its logical result in the political field. While doing this he, however, introduced an approach that was crucially important for the development of modern European political thought. The process of secularization of politics which had begun with Marsiglio of Padua reached its culmination in Machiavelli s writings. Free from mediaeval inhibitions Machiavelli gave a fully secular content and character to politics, granting it the fullest autonomy and thus laid the first important milestone of modernism in European political ideas.

Secularization of Politics In Prince Machiavelli makes it quite clear that his path is different from what has been followed by his predecessors in that he is only interested in exploring the factual truth of politics. In order to get at this factual truth he delinks politics from two of its old associations- one, theology and the other, ethics. But Machiavelli s general attitude, however, is far from anti-religious. In his Discourses he clearly recognizes religion as a social force. He even goes to the extent of admitting that the ruler, as one of his important political strategies, must play on the religious sentiments of his people and must, therefore, give due reverence to all religious observances.

Secularization(contd.) Although Machiavelli thus prizes the political effects of religion he, however, never compromises his secularist stand. Religion ,to him, may at best be a convenient means to politics, but certainly not its sovereign determinant. Although he is not generally anti-religious, Machiavelli is very much hostile to Christianity. Machiavelli s modernism is further reinforced by his denial of the uses of ethics in the political sphere. However, he is not a stubborn anti-moralist. Machiavelli does not deny the role of given moral rules in the private lives of individuals. But he makes a distinction between private morality and public morality and believes that the private norms of morality actually have no bearing on the public sphere of politics the imperatives of which give birth to a new kind of morality that goes much against what is viewed as moral in the private sphere.

Politics has its own Morality The underlying assumption is that the formation of a nation state in Italy is too stupendous a task that is hardly attainable by the so-called moral means and for the sake of this goal the ruler must take to whatever violence and cruelty, falsehood and breach of faith are needed to accomplish this task. After erecting the secular foundation of politics Machiavelli proceeds further to provide its content. The content of politics, according to him, is nothing but power. It is around the problem of how to acquire and to preserve power against all odds which hover Machiavelli s ideas as developed in both the Prince and the Discourses. Machiavelli, however, is least interested in questions like whether power as such is morally just or what are the possible ways of validating it.

Power as an End in itself Machiavelli considers power as an end in itself and deems it unnecessary to morally validate it as to him morality ill suits the hard facts of power. Power is the ultimate end for without it most of the men inhabiting society being ungrateful, selfish and fickle will upset the stability and security of society by pursuing their narrow, selfish ends. In other words, power represents the very core of the state without which there can not be any unity and order and hence it requires no philosophical justification as it springs from a basic political necessity.

Power as(contd.) Secondly, according to Machiavelli, to have a right to hold this power one does not have to be morally superior or a chosen agent of God. Those alone deserve to be powerful who have the necessary skill to wrest it for themselves, adopting whatever means are found suitable for this end. One who acquires this power and exercises it without challenge is the ruler for whom the greatest concern is how to preserve it. The ruler must not allow others to be powerful; he alone must have the whole of it. This power, however, can not be exercised against a hostile populace. Hence there is the need of securing the acquiescence of the people as a whole. Thus Machiavelli suggests that the ruler must not hesitate to indulge in brute force, cruelty and cunning.

Acquiescence of the People The ruler should tend to be more feared than loved and must not be ashamed of frequently breaking his words. He must be both a lion and a fox- a lion flashing in physical strength and a fox excelling in cunning. In other words, he should not care for the intrinsic goodness of means. It thus appears that Machiavelli frees power from the tightening belts of morals and religion. Power is a product neither of man s moral virtues nor of his divine life. Rather, it results from his own arms- from his own brute physical force.

No Interest in Legitimizing the Authority of the State Machiavelli had scant interest in questions like legitimizing the authority of the state, formulating safeguards for a smooth operation of this authority and establishing an apparent harmony between the interests of the sovereign and the subjects. Machiavelli, being a man of action, was more keen on suggesting concretely as to what was to be done rather than on building up a theoretical model. And he gave his suggestions quite candidly without any touch of hypocrisy. But, for his frank advices, he had to pay a great price. Most of the modern Western political thinkers who owe him all the perspective of their political theorization have completely disowned him.