State Privilege to Refuse Production of Documents in Courts: A Comparative Analysis between Great Britain and India

Doctrine of state privilege allows governments certain privileges, such as the right to refuse production of documents in courts. This privilege is recognized in both Great Britain and India, with specific statutory provisions defining its scope and application. In Great Britain, the Crown's powers to withhold documents have evolved over time, while in India, the privilege is based on the Evidence Act of 1872. The privilege is subject to limitations and judicial scrutiny in both jurisdictions.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

LL.M. SEMESTER II COURSE CODE : 204E (GR-B) COURSE TITLE : COMPARATIVE ADMINISTRATIVE LAW UNIT V : STATE PRIVILEGE TO REFUSE PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS IN COURTS, RIGHT TO INFORMATION AND OFFICIAL SECRETS ACT 5.1 STATE PRIVILEGE TO REFUSE PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS IN COURTS IN GREAT BRITAIN AND INDIA Presented by Dr. Sangeeta Chatterjee Assistant Professor Department of Law, Bankura University

INTRODUCTION Though the equality clause absence of government, but government is allowed certain state privileges. Since government is a government in contradistinction to a private individual, law allows certain privileges to the government as a litigant. From among numerous privileges available to the government under various statutes, one important is state privilege to refuse production of documents in courts. This doctrine is available in Great Britain and India. Though this doctrine is flourished by judicial creativity, but it has statutory provisions also. of the Constitution envisages privileges to anyone any special including

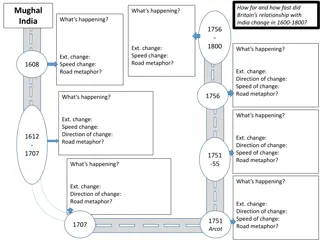

POSITION IN GREAT BRITAIN In England until the Second World War, it was generally recognized in the courts that the Crown s powers to forbid the disclosure of specified evidencewas not absolute. However, the law took a sharp turn in the wrong direction in 1942 when the House of Lords decided Duncan v. Cammel Laird and Co. Ltd., 1942. In that case, the House of Lords ruled that, if a Minister claims privilege for any document on the ground of public interest, it shall be considered as final and conclusive. This judicial abdication, however, can be justified in view of the special circumstances attending the case. The Lord Chancellor pointed out that, as to oral communications, the privilege was available on the same principles as in the case of written communications.

POSITION IN GREAT BRITAIN In England, the privilege to withhold documents cannot be referred to as Crown privilege. A private person may raise the same claim and the court itself may, of its own motion, refuse to permit disclosure. Therefore, it can be rightly called a public interest privilege. In England now, Section 28 of the Crown Proceedings Act, 1974 specifically recognizes the right of the Crown to withhold documents, if in the opinion of the relevant Minister it would be injurious to the public interest to disclose them. However, the claim of privilege is to be decided by the judge and not by the executives. Exceptions are documents relate to national security, diplomatic relations or State secrets of high importance. In all other cases, the court shall have the power to inspect the document.

POSITION IN INDIA In India, the privilege of the government to withhold documents from the courts is claimed on the basis of Section 123 of the Evidence Act, 1872. It lays down that, no one shall be permitted to give any evidence derived from unpublished official records relating to the affairs of the State. Exception is with the permission of the head of the department concerned, who shall give orwithhold such permission as he thinks fit. Section 124 extends this privilege to confidential official communication also. The privilege claimed is not conclusive in the sense that the courts can do nothing except to admit it. This proposition is based on Section 162 of the Evidence Act, 1872. It provides that, when a witness is required to produce a document, he must bring it to the court and then may raise an objection to its production and admissibility.

POSITION IN INDIA In State of Punjab v. Sodhi Sukhdev Singh, 1961, the court had the opportunity of discussing the extent of government privilege to withhold documents where twin claims of governmental confidentialityand individual justice compete forrecognition. The court elaborated the extent of privilege by holding that, the government documentscan be classified into twocategories : 1. Documents relating to the affairsof the State; and 2. Documents not relating to the affairsof the State. For the second categorydocuments, there is no immunity. But for the first category documents, the claim of the privilege is not conclusive and the court is required to enquire into the nature of the document in the light of relevant factsand circumstances. However, the court held that, in order to determine the claim of privilege, the court cannot inspect the document. The administration shall be the sole judge of the public interest involved in the disclosure.

MEASURES TO PREVENT MISUSE The claim of privilege should be in the form of an affidavit which must be signed by the Minister concerned or the Secretary of thedepartment. The affidavit must indicate within permissible limits the reasons why the disclosure would result in public injury, and that the document in question has been carefully read and considered and the authority is fully convinced that its disclosure would injure public interest. If the affidavit is found unsatisfactory, the court may summon theauthority forcross-examination.

FACTORS TO BE CONSIDERED FOR DECIDING PUBLIC INTEREST IMMUNITY CLAIMS The court further amplified the law by laying down the factors to be considered in deciding the public interest immunity claims. These factors would include the following : Interestaffected by the disclosureof the document. In case of class protection Whether the public interest immunity protects the class. The extent to which the interests referred to have become attenuated by the passageof timeor intervening events. The seriousness of the issue by which production of the document is sought. The likelihood that production of the document will affect the outcome of thecase. The likelihood of injustice if the document is not produced.

CRITICISM The privilege is a narrow one, to be exercised only where there is some plain overriding principleof public policy. Only rarely can documents relating to the industrial or commercial activities of the State come within the rule, especially in times of peace. The mere fact that the production of a document might prejudice the Crown s own case is not a justification fora claim of privilege. The court is entitled to require, and should require, an actual affidavit from a responsible Minister whose mind has been directed to the questions involved. In all cases, the court has in reserve its power to inspect the document in question.

FUTURE PROPOSITIONS The privilegewould not forthe future be claimed in respectof certain classes of documents : In relation to road accidents, accidents involving government employees and accidents on government premises, reports of the employees involved and other eyewitnesses and subsequent report made by the foreman, superintendent or other official as to such matters as the state of the machinery, vehicle or premises involved. This class does not include reports of a government inspector, etc. investigating an industrial or mining accident. Ordinary medical reports in respect of the health of civilian employees. This class does not include medical reports and records in the fighting services and in the prison service, though the privilege would not be claimed in proceedings against the medical officer concerned for negligence, or in criminal proceedings. Statements made to the police (except by informers ). These would be produced in court on subpoenaor furnished earlierwith theconsentorat the requestof thewitnesses themselves. In contract cases, all documents passing between the parties, other documents affecting the legal position (forexample, an authority to an agent), and relevant reports on matters of fact (as distinct fromcommentand advice).

CONCLUSION In S. P. Gupta v. Union of India, 1981, the Supreme Court rejected the government s claim of privilege over the correspondence relating to the transfer and non-extension of the terms of two judges of High Courts. After studying the documents in the chamber, the judges came to the conclusion that the documents did not belong to the privileged category covering affairs of State and their disclosure would not jeopardize public interest. In arriving at this conclusion, the court applied the balancing of interest test. It was stressed that, in the ultimate analysis the approach of the court, while deciding the question of privilege, would be that it has to balance public interest in just justice and just administration of justice and State affairs and then decide which way the balance tilts.

REFERENCE : 1. Dr. I. P. Massey, Administrative Law, Eastern Book Company, Lucknow, 8th Edition, 2012.