Understanding Seizures and Epilepsy: A Practical Guide for Primary Care Providers

This practical guide provides valuable insights into seizures and epilepsy for primary care providers, covering topics such as different seizure types, epilepsy definition and treatment initiation, antiseizure medications, and status epilepticus management. Terminology and a clinical scenario are discussed to enhance understanding and decision-making in seizure emergencies.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Seizure and Epilepsy: A Practical Guide for Primary Care Providers Sarah Durica, M.D. Assistant Professor Department of Neurology The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center OU Neurology

EXPERIMENTAL OR OFF-LABEL DRUG/THERAPY/DEVICE DISCLOSURE I will be discussing off-label drugs, therapies, and/or devices that have not been approved by the FDA. OU Neurology

LEARNING OBJECTIVES At the end of this session, the attendee will be able to: Define seizure and list the different seizure types Differentiate provoked and unprovoked seizures Define epilepsy, discuss when to initiate treatment, and appropriately select initial treatment options Discuss the interactions and side effects of commonly used antiseizure medications Define status epilepticus and describe the treatment pathway OU Neurology

Terminology Seizure: transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain Generalized seizures involve the whole brain from the beginning of the seizure. There are several types of generalized seizures including: Tonic-clonic ( grand mal ) Absence ( petite mal ) Atonic ( drop ) Myoclonic (jerks) Focal seizures start in one part of the brain and may or may not spread to involve the whole brain. There are two main types of focal seizures: In focal aware seizures, the person remains alert. These were previously called simple partial seizures In focal impaired awareness seizures,the person has confusion or loses awareness/consciousness. These were previously called complex partial seizures OU Neurology

Terminology OLD NEW Location Focal Partial Generalized Generalized Unknown Aware Simple awareness Level of Impaired awareness Complex Focal to bilateral tonic- clonic Spread Secondary generalized ILAE 2017 OU Neurology

Question A 21-year-old man with history of type 1 diabetes presents to the hospital with a new-onset generalized tonic-clonic seizure that lasted 5 minutes. He is drowsy, but answers questions. He is diaphoretic and tachycardic and has whole body tremors. A fingerstick blood glucose is 38. The remainder of his labs are pending. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in management? 1. Levetiracetam 20 mg/kg IV 2. Lorazepam 2 mg IV 3. STAT EEG to rule out continued seizures/nonconvulsive status epilepticus 4. Thiamine 100 mg IV followed by 50 ml D50W IV 5. Lorazepam 2 mg IV followed by levetiracetam 20 mg/kg OU Neurology

Acute Symptomatic (Provoked) Seizures Clinical seizures occurring at a time of systemic insult or in close temporal association with a documented brain insult Occur due to an identifiable proximate cause and should not recur if that cause is eliminated and avoided in the future Systemic insult is defined as: In the presence of severe metabolic derangements Drug or alcohol intoxication or withdrawal Exposure to well-defined epileptogenic drugs Eclampsia Close temporal association is defined as: Within 1 week of stroke, traumatic brain injury, anoxic encephalopathy, or intracranial surgery At the first identification of a subdural hematoma During an active central nervous system infection During active phase of multiple sclerosis or other autoimmune disease Beghi et al., 2010 OU Neurology

Metabolic Causes of Acute Symptomatic Seizures The more rapidly metabolic changes occur, the more likely they are to induce seizures No good data to guide clear cutoff values for lab abnormalities associated with seizures Note: the values on the right are at the extreme end, favoring specificity over sensitivity (reducing false positives) These are not the only metabolic causes. Other causes include: hypernatremia, hypoxia, hyperthyroidism, porphyria, dialysis disequilibrium syndrome Beghi et al., 2010 OU Neurology

Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures Indicators of acute symptomatic seizures from alcohol withdrawal include: History of chronic heavy alcohol use History of current alcohol use with recent reduction in consumption Generalized tonic-clonic seizure Other signs/symptoms of alcohol withdrawal like tremors, diaphoresis, tachycardia The seizure must occur within 7-48 hours of last drink Note: this is different from delirium tremens (DTs), which typically begins 48-96 hours after the last drink Withdrawal seizures can also occur with cessation of benzodiazepines and barbiturates Can also have acute symptomatic seizures in setting of alcohol intoxication Beghi et al., 2010 OU Neurology

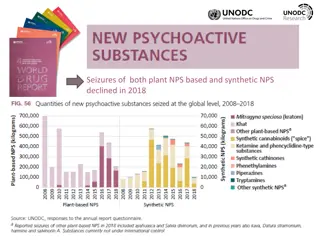

Acute Symptomatic Seizures Due To Illicit/Street Drugs and Marijuana Some substances have a high probability that they are the etiologic cause if associated with seizures: Cocaine (if metabolites are found in blood or urine) Meperidine/normeperidine Methaqualone (Quaaludes) Stimulants taken in excess (e.g. MDMA/ecstasy) Inhalants Hallucinogens and phencyclidine (PCP) have fair probability Heroin and marijuana have low or no probability Beghi et al., 2010 OU Neurology

Treatment of Acute Symptomatic Seizures Most important treatment is correction and avoidance of the underlying cause of the seizure If the provoking cause is likely to be ongoing for a time (e.g. meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, etc.), treatment with antiseizure medication can be considered until resolution of the trigger No good data to guide the selection of best antiseizure medication selection based on patient age and sex, formulation of medication (e.g. IV vs. PO), medical comorbidities, other medications, urgency of treatment, suspected duration of treatment, and other factors OU Neurology

Prevention of Acute Symptomatic Seizures Robust data is lacking in most cases Evidence suggests that prophylactic treatment with antiseizure medications (phenytoin or levetiracetam) for 7 days after severe traumatic brain injury decreases risks of early seizures, though does not decrease epilepsy risk long term No indication for routine prophylaxis with antiseizure medications in: Brain neoplasm (primary or metastatic) Meningitis Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) Intracerebral hemorrhage Arteriovenous malformations or cavernomas Ischemic stroke Postoperative craniotomy Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis Yerrem et al., 2018 OU Neurology

Answer A 21-year-old man with history of type 1 diabetes, asthma, and hypothyroidism presents to the hospital with a new-onset generalized tonic- clonic seizure that lasted 5 minutes before stopping on its own. He is still drowsy, but does awake and answer some questions, though is disoriented. He is diaphoretic and tachycardic and has fast whole body tremors. A fingerstick blood glucose is 35, but the remainder of his labs are still pending. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in management? 1. Levetiracetam 20 mg/kg 2. Lorazepam 2 mg IV 3. STAT EEG 4. Thiamine 100 mg IV followed by 50 ml D50W IV 5. Lorazepam 2 mg IV followed by levetiracetam 20 mg/kg Hypoglycemia is a known cause of acute symptomatic seizures. He has classic symptoms of hypoglycemia, which is confirmed by the fingerstick blood glucose. Since he is improving after the seizure, it is unlikely that he is in status. Hypoglycemia can be associated with a diffuse tremulousness that should not be confused with ongoing tonic-clonic activity. OU Neurology

Epilepsy Definition Epilepsy is a disease where a person has a risk of recurring, unprovoked seizures Three definitions of epilepsy: 1. At least two unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart 2. One unprovoked or reflex seizure and a probability of at least 60% of having another seizure within 10 years 3. Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome Epilepsy is considered resolved: When a patient with an age-dependent epilepsy syndrome is older than the age for which the syndrome was active, or A patient has been seizure free for 10 years and off all antiseizure medications for 5 years OU Neurology

Seizure/Epilepsy Workup Seizures and epilepsy are clinical diagnoses no test is required to make the diagnosis Most important aspect of diagnosis is a good history Assess for any provoking factors Assess for previous, unrecognized seizures as many people do not realize focal, absence, or myoclonic seizures are seizures Assess for historical factors that may increase risk of epilepsy Febrile seizures as a child Family history of epilepsy (genetic epilepsy syndromes) History of CNS infections (meningitis/encephalitis) Severe traumatic brain injury Other brain lesions like tumors, stroke, dementia On exam look for any focal findings that may suggest a brain lesion and look at the skin (many neurocutaneous syndromes are associated with seizures) OU Neurology

Seizure/Epilepsy Workup Per a retired* 2007 practice parameter of The American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society published on evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure: EEG and brain imaging with CT or MRI should be obtained in adults presenting with an apparent unprovoked first seizure (Level B) Laboratory tests, such as blood counts, blood glucose, and electrolyte panels (particularly sodium), lumbar puncture, and toxicology screening may be helpful as determined by the specific clinical circumstances based on the history, physical, and neurologic examination, but there are insufficient data to support or refute recommending any of these tests for the routine evaluation of adults presenting with an apparent first unprovoked seizure (Level U). For a first unprovoked seizure and for all patients diagnosed with epilepsy, I personally obtain an EEG and an epilepsy/seizure protocol MRI brain without contrast (with contrast if I suspect tumor, infection, or autoimmune disease). If they come into the ED acutely I request CBC, chemistries, and urine drug screen as well. *Guidelines were retired per automatic retirement policy which mandates retirement of guidelines that have not been updated or reaffirmed within five years after publication or last reaffirmation. Retired guidelines are no longer valid and no longer supported by the AAN Krumholz et al., 2007 OU Neurology

Management of a first unprovoked seizure For those with two or more unprovoked seizures or who meet criteria for epilepsy start an antiseizure medication The management of those with a single unprovoked seizure is more complicated, particularly since one typically does not have the workup required to determine a seizure recurrence probability at the time of initial evaluation Unless a seizure is obviously provoked, they should be evaluated by a neurologist. This can be outpatient if the patient is back to baseline with a normal neurologic exam OU Neurology

Management of a first unprovoked seizure assessing risk of seizure recurrence After a first unprovoked seizure there is a 36% risk of seizure recurrence within one year and 46% risk of recurrence within 5 years Most consistent risk factors associated with increased risk for seizure recurrence: Prior brain lesion or insult EEG with epileptiform abnormalities Significant brain imaging abnormality Nocturnal seizure Krumholz et al., 2015 OU Neurology

Management of a first unprovoked seizure treatment with an antiseizure medication Immediate therapy with an antiseizure medication (ASM) after an unprovoked first seizure reduces risk of seizure recurrence in the short term (35% absolute risk reduction) However, one Class II study showed no difference in 2-year quality of life measures Immediate treatment after an unprovoked first seizure as compared with treatment delayed pending a second seizure does not increase the chance of sustained seizure remission Risk of adverse effects from ASM ranges from 7-31% (but mostly old drugs studied) Krumholz et al., 2015 OU Neurology

Management of a first unprovoked seizure so should I treat or not? Official guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society recommend discussing the information in the previous two slides with patients, but make no recommendation on when to start treatment In my personal practice: For patients with one unprovoked seizure and an abnormal EEG or brain imaging, I typically recommend starting antiseizure medications For those with normal workup, I discuss the evidence with patients and tell them that either starting or deferring antiseizure medications is reasonable OU Neurology

Epilepsy Treatment Treatment with antiseizure medications is recommended for those who meet the diagnostic criteria for epilepsy Always start with monotherapy (one medicine) first Approximately 50% will become seizure-free with first antiseizure medication Data on comparative efficacy and tolerability are limited (no best drug for every patient) Considerations: Drug effectiveness for seizure type Interactions with other medications Comorbid medical conditions (especially hepatic and renal disease) Potential adverse effects of the medication Age and gender, especially regarding pregnancy plan Lifestyle and patient preference Dosing schedule (daily, BID, TID, QID) Formulation (pill, liquid, IV, sprinkle) Cost OU Neurology

Drug Effectiveness for Seizure Type Narrow Spectrum (Focal Seizures) Carbamazepine (Tegretol) Cenobamate (Xcopri) Eslicarbazepine (Aptiom) Gabapentin (Neurontin) Lacosamide (Vimpat) Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) Phenobarbital Phenytoin (Dilantin) Pregabalin (Lyrica) Primidone Tiagabine (Gabitril) Vigabatrin (Sabril) Broad Spectrum (Generalized and Focal Seizures) Brivaracetam (Briviact) Clobazam (Onfi) Felbamate (Felbatol) Lamotrigine(Lamictal) Levetiracetam (Keppra) Perampanel (Fycompa) Rufinamide (Banzel) Topiramate (Topamax) Valproate (Depakote, Depakene) Zonisamide (Zonegran) OU Neurology

Enzyme-Inducing Antiseizure Medications Inducing antiseizure medications include: Carbamazepine Phenytoin Phenobarbital To a lesser extent, topiramate and oxcarbazepine Inducers are most problematic for interactions with warfarin, statins, calcium channel blockers, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors , antipsychotics, oral contraceptives, certain cancer therapies, and certain anti-infectious drugs Brodie et al., 2012 OU Neurology

Enzyme-Inducing Antiseizure Medications Brodie et al., 2012 OU Neurology

Renal Disease and Antiseizure Medications Gabapentin, pregabalin, topiramate, zonisamide, lacosamide, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine are renally excreted Adjust dose based on severity of renal impairment Renally excreted drugs and some others (e.g. lamotrigine and phenobarbital) are removed by hemodialysis Supplement dose after dialysis Low serum albumin associated with renal disease can increase free fraction of highly protein-bound drugs (valproate and phenytoin) Monitor free and total fraction of the drug Topiramate and zonisamide are associated with nephrolithiasis and renal tubular acidosis OU Neurology

Hepatic Disease and Antiseizure Medications Valproate and felbamate (and to a lesser extent, phenytoin and carbamazepine) are associated with hepatic toxicity Carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, clobazam, valproate, felbamate, zonisamide, topiramate, oxcarbazepine, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam are fully or partially metabolized by the liver Caution and possible dose adjustment depending on severity of liver disease Levetiracetam, gabapentin, pregabalin, and vigabatrin do not undergo hepatic metabolism Reason for minimal drug interactions OU Neurology

Psychiatric Disorders and Antiseizure Medications Psychiatric disorders are common comorbidities in people with epilepsy Valproic acid, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine have mood stabilizing properties FDA warning for antiseizure medications as a class for increased suicidality GABAergic drugs (phenobarbital, topiramate, vigabatrin, tiagabine) can cause or worsen depression Psychosis has been associated with levetiracetam, topiramate, vigabatrin, zonisamide, ethosuximide, and perampanel Remember: enzyme-inducing seizure drugs can decrease levels of antidepressants and antipsychotics OU Neurology

Antiseizure Medications and Osteoporosis I recommend calcium and vitamin D supplements for most patients on antiseizure medications Sazgar 2019 OU Neurology

Antiseizure Medications and Other Medical Comorbidities Migraine: topiramate, zonisamide, valproate, and (maybe) gabapentin are effective at migraine prophylaxis Diabetes: Valproate is associated with weight gain and insulin resistance Gabapentin and pregabalin treat diabetic neuropathy Obesity: Valproate and less frequently carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and vigabatrin are associated with weight gain Topiramate and zonisamide are associated with weight loss Cardiovascular disease: Enzyme-inducers may affect statins, antihypertensives, warfarin, and clopidogrel Cytochrome P450 enzymes are involved with cholesterol synthesis, and enzymes inducers are associated with higher cholesterol. However, no studies have linked specific antiseizure medications to high risk of vascular events Blood dyscrasias: Neutropenia and agranulocytosis: carbamazepine, valproate, phenytoin Thrombocytopenia: valproate, carbamazepine, phenytoin OU Neurology

Antiseizure Medications and Teratogenicity *Risk of malformations must be balanced by risk of seizures, which are harmful to mother and fetus. Some risks can be reduced with folic acid supplementation. Never abruptly stop an antiseizure medication just because a patient becomes pregnant. Avoid if possible* My personal first- line in pregnancy Abou-Khalil 2019 OU Neurology

Question A 73-year-old woman with a history of focal epilepsy, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the hospital for a several-day history of dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and increased seizures. Her vital signs are normal and her neurologic exam reveals bilateral nystagmus. Her blood work shows sodium of 120 mEq/L. Her medications include amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide, and metformin. She was recently started on a new antiseizure medication, but cannot remember the name. Which of the following medications is most likely to have caused her symptoms? 1. Carbamazepine 2. Levetiracetam 3. Oxcarbazepine 4. Phenytoin 5. Topiramate OU Neurology

Antiseizure Medications and Adverse Effects Many side effects are common to antiseizure medications as a class: Drowsiness/fatigue or insomnia Diplopia Ataxia Suicidality/worsening mood (FDA class warning) Hypersensitivity reactions (most commonly the enzyme inducers + lamotrigine) Start low, increase slowly for further seizures OU Neurology

Lamotrigine (Lamictal) Broad spectrum: effective for focal and generalized seizures (though may worsen myoclonic seizures) Formulation: oral only Adverse effects: rash (Stevens-Johnson), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) Drug interactions: clearance is decreased by valproate and increased by estrogen, pregnancy, and enzyme inducers PCP takeaway: if a patient is on lamotrigine, caution using oral contraceptive pills PCP takeaway: if a patient is on lamotrigine, caution starting valproic acid. If a patient is on valproic acid, must start a reduced dose of lamotrigine Best safety data in pregnancy Must be started gradually OU Neurology

Levetiracetam (Keppra) Broad spectrum: effective for focal and generalized seizures Formulation: oral and IV Adverse effects: irritability, mood effects, psychosis, pancytopenia Irritability may improve with vitamin B6 100 mg daily Drug interactions: no significant interactions Safe in pregnancy OU Neurology

Topiramate (Topamax) Broad spectrum: effective for focal and generalized seizures Also FDA approved for migraine treatment and as weight-loss preparation in combination with phentermine Formulation: oral only Adverse effects: cognitive effects, word finding difficulty, nephrolithiasis, decreased sweating, acute angle closure glaucoma, decrease appetite/weight loss, paresthesias Drug interactions: Mild inducer of CYP3A4 reduces efficacy of oral contraceptives at doses greater than 200 mg/day Mild inhibitor of CYP2C19 Pregnancy: 4% risk of congenital malformations, particularly oral clefts OU Neurology

Valproate (Depakote, Depakene) AKA valproic acid and divalproex sodium Broad spectrum: effective for focal and generalized seizures Also FDA approved for migraine and bipolar disorder Formulation: oral and IV Divalproex has DR (BID to TID) and ER (daily) formulations that are NOT equivalent Adverse effects: tremor, hair loss, hyperammonemic encephalopathy (even if LFTs normal), thrombocytopenia, polycystic ovarian syndrome, insulin resistance, idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity and pancreatitis Drug interactions: Highly protein bound: caution with other highly-protein bound drugs (phenytoin) Potent inhibitor: reduces clearance of lamotrigine, phenobarbital, rufinamide, and carbamazepine epoxide Pregnancy: high risk of malformations, supplement folic acid OU Neurology

Carbamazepine (Tegretol) Narrow spectrum: effective for focal and generalized tonic-clonic seizures Exacerbates absence, atonic, and myoclonic seizures Also FDA approved for trigeminal neuralgia, acute mania, and bipolar disorder Formulation: oral Adverse effects: hyponatremia, mild leukopenia (in 10-20%, usually benign), aplastic anemia (1 in 200,000), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare, associated with HLA-B1502 phenotype in people of Asian descent), lupus- like syndrome, hepatotoxicity, hypersensitivity syndrome Drug interactions: Potent inducer Also demonstrates autoinduction: increased clearance of itself over 2-4 weeks Pregnancy: intermediate risk OU Neurology

Oxcarbazepine (Triletpal) Narrow spectrum: effective for focal seizures May exacerbate absence and myoclonic seizures Formulation: oral Adverse effects: hyponatremia (higher risk than carbamazepine, especially with diuretics), rash (25% cross reactivity with carbamazepine) Drug interactions: Weak inducer of CPY3A4 Reduces efficacy of oral contraceptives at doses higher than 900 mg/day Weak inhibitory of CYP2C19 Increases phenytoin when used at higher doses Pregnancy: low risk of congenital malformations OU Neurology

Lacosamide (Vimpat) Narrow spectrum: focal seizures However, preliminary data suggests it does not worsen absence or myoclonic seizures Formulation: oral and IV Adverse effects: dose-dependent prolongation of PR interval, AV block Drug interactions: minimal Pregnancy: limited data OU Neurology

Phenytoin (Dilantin) Narrow spectrum: focal and generalized tonic-clonic seizures May exacerbate absence and myoclonic seizures Formulation: oral and IV Fosphenytoin is prodrug which can be given IV and IM Adverse effects: gingival hypertrophy, paradoxical increase in seizures if toxic, hypotension and arrhythmia (IV formulations) Drug interactions: Potent P450 enzyme inducer 90% protein bound: caution with other highly-protein bound drugs (valproic acid), renal/liver disease, and low protein states Non-linear kinetics with saturable metabolism Pregnancy: intermediate risk (orofacial and cardiac defects, cognitive) OU Neurology

Marijuana and Cannabidiol in Epilepsy Cannabidiol (CBD: marketed under brand name Epidiolex) is FDA indicated for treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome or Dravet Syndrome in patients 2 years old Formulation: oral liquid Adverse effects: sedation, fatigue, decreased appetite, diarrhea, transaminitis (requires intensive LFT and bilirubin monitoring) Drug interactions: Highly protein bound (> 94%) Clearance increased by inducers and decreased by inhibitors of CYPC19 and CYP3A4 Pregnancy safety: unknown OU Neurology

Marijuana and Cannabidiol in Epilepsy What Do I Say? Medical marijuana (THC or THC/CBD combination) has not been shown to be effective at treating epilepsy or preventing seizures Small studies show that CBD is effective for two very specific types of epilepsy that occur most frequently in children Medical/recreational marijuana and CBD preparations are not regulated by the FDA, so the dosage you get is uncertain The dose of CBD that is effective for preventing seizures is significantly higher than the dose in medical/recreational marijuana and over-the- counter CBD preparations As such, just like other medications, CBD is associated with significant side effects like drowsiness, diarrhea, and liver toxicity CBD can interact with other medications I do not recommend medical marijuana or OTC CBD for the treatment of epilepsy for these reasons If I think CBD is appropriate for the patients epilepsy, I use prescription formulations OU Neurology

Answer A 73-year-old woman with a history of focal epilepsy, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the hospital for a several-day history of dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and increased seizures. Her vital signs are normal and her neurologic exam reveals bilateral nystagmus. Her blood work shows sodium of 120 mEq/L. Her medications include amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide, and metformin. She was recently started on a new antiseizure medication, but cannot remember the name. Which of the following medications is most likely to have caused her symptoms? 1. Carbamazepine 2. Levetiracetam 3. Oxcarbazepine 4. Phenytoin 5. Topiramate Oxcarbazepine is associated with hyponatremia in 10-30% of patients. Usually this is asymptomatic, but can be severe in some, requiring changes in medications. Carbamazepine is associated with hyponatremia as well, but not to the same extent as oxcarbazepine. The risk of hyponatremia is higher in the elderly and with those taking other medications that can lower sodium. A paradoxical worsening of seizures can be seen due to hyponatremia. OU Neurology

Question A 20-year-old woman with history of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome presents to the emergency department for a generalized tonic-clonic seizure that started 15 minutes ago. Her home medication regimen includes levetiracetam 2000 mg BID, valproate 1500 mg BID, and clobazam 10 mg BID. She weighs 60 kg. Which of the following is the most appropriate next management step after assessing her respiratory and cardiac stability? 1. Fosphenytoin 20 mg PE/kg IV 2. Levetiracetam 20 mg/kg IV 3. Lorazepam 1 mg IV 4. Midazolam 10 mg IM 5. Valproic acid 40 mg/kg IV OU Neurology

Status Epilepticus - Definition Condition resulting either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms that lead to abnormally prolonged seizures Conceptual definition with two operational dimensions: t1: The time point beyond which the seizure should be regarded as continuous seizure activity and is when treatment should be initiated t2:The time of ongoing seizure activity after which there is a risk of long-term consequences Convulsive status epilepticus: t1 = 5 minutes t2 = 30 minutes Based on incomplete and variable animal experiments and clinical research treat as framework and not doctrine ILAE 2015 OU Neurology

Treatment of Generalized Convulsive Status Epilepticus Note the dosing! Doses are often higher than many providers would typically give! Early treatment is essential as seizures become more refractory to treatment the longer they continue Even if seizures stop after a benzodiazepine, a nonbenzodiazepine antiseizure drug should be given to prevent seizure recurrence * * * * * FDA approved for treatment of status epilepticus 0.1 mg/kg/dose, max 4 mg/dose 10 mg > 40 kg, 5 mg for 13-40 kg Lacosamide -Neurocritical Care Society: 200 mg IV over 15 minutes -Some experts: up to 400 mg at rate 80 mg/min * Edited from Betjemann et al., 2015 OU Neurology

Answer A 20-year-old woman with history of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome presents to the emergency department for a generalized tonic-clonic seizure that started 15 minutes ago. Her home medication regimen includes levetiracetam 2000 mg BID, valproate 1500 mg BID, and clobazam 10 mg BID. She weighs 60 kg. Which of the following is the most appropriate next management step after assessing her respiratory and cardiac stability? 1. Fosphenytoin 20 mg PE/kg IV 2. Levetiracetam 20 mg/kg IV 3. Lorazepam 1 mg IV 4. Midazolam 10 mg IM 5. Valproic acid 40 mg/kg IV second-line agents if benzodiazepine fails. While the listed doses of fosphenytoin and valproic acid are appropriate status dosing, the levetiracetam dose is on the low end of some society recommendations for status epilepticus. After a benzodiazepine is given, a normal loading dose of a longer-acting antiseizure medication (such as levetiracetam 20 mg/kg IV) is appropriate to prevent seizure recurrence. Benzodiazepines are the most appropriate first-line treatment for status epilepticus. Midazolam, lorazepam, and diazepam are appropriate choices. However, lorazepam 1 mg IV is too low a dose and for status epilepticus lorazepam should be dosed at 0.1 mg/kg with a max of 4 mg per dose. Midazolam can be given 10 mg IM, and this is actually the recommended route pre-hospital. Fosphenytoin, valproic acid, and levetiracetam can be used as OU Neurology

Patient Education Patient counseling and education is very important after the diagnosis of seizure or epilepsy After diagnosis, patients may suffer a number of losses, including loss of independence, employment, ability to drive, and self-esteem Patients should be aware of common seizure triggers or precipitating factors, including sleep deprivation, alcohol, certain medications, and infection or systemic illness. Patients should be advised to avoid unsupervised activities that might pose danger with sudden loss or alteration of consciousness, including bathing (showers are safer than baths), swimming (never swim alone and wear life vest around water), working at heights, operating heavy machinery, using power tools, using heated appliances (cooking, hair styling, etc). I also caution unsupervised care of young children. Patients should also be educated specifically on seizure first aid and driving precautions OU Neurology

Seizure First Aid Things to do: Stay with the person until they are fully recovered Time the seizure with your phone or clock Ease the person to the floor Roll the person onto their side Move any dangerous objects away Put something soft underneath the person s head Loosen any tight clothing around the neck Call 911 for seizures > 5 minutes, multiple seizures without return to baseline, seizures in water, or if patient pregnant, diabetic, or sick Things NOT to do: Do not put anything into the person s mouth Do not hold the person down to try to stop their movements Do not put water onto the face Do not try to give CPR or mouth-to- mouth breaths since people usually start breathing again after the seizure is over Do not give the person something to eat or drink until the person is fully awake OU Neurology

Seizures/Epilepsy and Driving Every state puts limits on driving for people with seizures. These laws vary from state to state. Oklahoma law says you must be episode free for 6 months and submit a favorable recommendation for driving from a physician Commercial driving requirements are more restrictive Oklahoma does not require physicians to report patients to the Department of Public Safety, but does protect physicians who make good faith reports OU Neurology